I think my relationship with story-telling – with books and films – is different from many other people’s relationship. This is especially so in the sensory impact of stories, where perhaps emotional and sensory feelings intermingle, changing the sense of the story. My perception of the story is different from the people around me. I don’t know how much of that is ‘autistic’, or neurological, or natural human variation. The colour we know by the word ‘red’, for instance, does not represent the same sensory experience for all people because our eyes and brains differ. The word ‘red’ itself also differs, through past association and learning. And – according to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis – we might not even consciously perceive ‘red’ if we did not have a symbolic word to represent the sensation.

Putting stories into narrative text and films are relatively recent modes of story-telling. Looking at stories conveyed through a single, static image is very revealing of the amount we can share through one common sensory touchstone, assisted (we assume) by language, gesture and ritual. The touchstones remain, like Stations of the Cross, to remind and strengthen after the words have faded.

This post is part of a much bigger, more wide ranging look at what ‘autism’ means and where it comes from. I hope to have a display of related imagery and text ready around November of this year.

Story-telling images

The earliest human images consist of lines, geometries and physical impressions of objects. We are still strongly moved by human hand in ochre at the Cueva de la Manos in Santa Cruz, Argentina, even though we can’t be sure what the artists were doing or thinking as they made them between 9,000 and 13,000 years ago. These images were rarely flat, the artists choosing convex and concave curves in the walls, and their shape alters as the light shifts. Werner Herzog, in “Cave of the Forgotten Dreams” (2010) says “you have to imagine lions, bears, leopards, wolves, foxes in very large numbers. And among all these carnivores and predators, human. Could it be how they set up fires in Chauvet Cave? There’s evidence that they cast their own shadows against the panels of horses, for example. The fire was necessary to look at the paintings and maybe towards staging people around. When you look with the flame, with moving light, you can imagine people dancing with the shadows. Like Fred Astaire.”

The earliest human images consist of lines, geometries and physical impressions of objects. We are still strongly moved by human hand in ochre at the Cueva de la Manos in Santa Cruz, Argentina, even though we can’t be sure what the artists were doing or thinking as they made them between 9,000 and 13,000 years ago. These images were rarely flat, the artists choosing convex and concave curves in the walls, and their shape alters as the light shifts. Werner Herzog, in “Cave of the Forgotten Dreams” (2010) says “you have to imagine lions, bears, leopards, wolves, foxes in very large numbers. And among all these carnivores and predators, human. Could it be how they set up fires in Chauvet Cave? There’s evidence that they cast their own shadows against the panels of horses, for example. The fire was necessary to look at the paintings and maybe towards staging people around. When you look with the flame, with moving light, you can imagine people dancing with the shadows. Like Fred Astaire.”

The images of Chauvet Cave could be very real expressions of the sense of having seen and hunted the animals they depict. It is possible to design a camera with a response resembling early art. In this image, a cheetah runs against a black backdrop. It is a living cheetah, from a video sequence showing their tremendous power and speed. Selecting sequential frames from the video and overlaying them on top of each other, the oldest frames fade away and the latest are most apparent. The image of the cheetah is repeated, over-and-over, capturing the essence of a cheetah running and without requiring the technology to play moving images.

The images of Chauvet Cave could be very real expressions of the sense of having seen and hunted the animals they depict. It is possible to design a camera with a response resembling early art. In this image, a cheetah runs against a black backdrop. It is a living cheetah, from a video sequence showing their tremendous power and speed. Selecting sequential frames from the video and overlaying them on top of each other, the oldest frames fade away and the latest are most apparent. The image of the cheetah is repeated, over-and-over, capturing the essence of a cheetah running and without requiring the technology to play moving images.

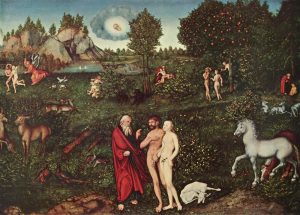

Our current wealth of visual story-telling grew substantially in the middle ages. Lucas Cranach the Elder depicted Adam and Eve many times, and in Paradise (1530) he portrays the story of Genesis 2 and 3 – God brought Eve forth from sleeping Adam’s rib, directed them to eat of everything but the Tree of Knowledge, discovered them naked and afraid, having been tempted by the (here half-woman) serpent, and expels them from the garden. The canvas is a collection of common touchstones for story-telling and story remembrance, by which people could share words before word-printing was common, and share moral instruction.

Our current wealth of visual story-telling grew substantially in the middle ages. Lucas Cranach the Elder depicted Adam and Eve many times, and in Paradise (1530) he portrays the story of Genesis 2 and 3 – God brought Eve forth from sleeping Adam’s rib, directed them to eat of everything but the Tree of Knowledge, discovered them naked and afraid, having been tempted by the (here half-woman) serpent, and expels them from the garden. The canvas is a collection of common touchstones for story-telling and story remembrance, by which people could share words before word-printing was common, and share moral instruction.

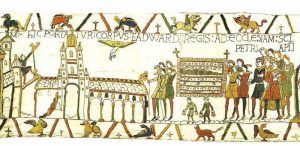

The Bayeux tapestry is an outstanding example of ambitious story-telling, embroidered on a 50 cm high tapestry that is 70 m long. It tells the (Norman perspective) of the death of Kind Edward the Confessor, who died with no children, having nominated William as successor. So began the Norman invasion of England, Harold’s death in Hastings and (later) the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland. This scene is one of 58 that survive – there are 2 linen panels missing from a total of 11. The scene is titled “Here the body of King Edward is carried to the Church of Saint Peter the Apostle” [“Hic portatur corpus Eadwardi Regis ad ecclesiam Sancti Petri Apostoli”]. The Bayeux tapestry is a linear progression, from the Edward’s death to Norman victory, unlike Cranach’s “Paradise” in which the scenes are distributed aesthetically over a canvas.

The Bayeux tapestry is an outstanding example of ambitious story-telling, embroidered on a 50 cm high tapestry that is 70 m long. It tells the (Norman perspective) of the death of Kind Edward the Confessor, who died with no children, having nominated William as successor. So began the Norman invasion of England, Harold’s death in Hastings and (later) the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland. This scene is one of 58 that survive – there are 2 linen panels missing from a total of 11. The scene is titled “Here the body of King Edward is carried to the Church of Saint Peter the Apostle” [“Hic portatur corpus Eadwardi Regis ad ecclesiam Sancti Petri Apostoli”]. The Bayeux tapestry is a linear progression, from the Edward’s death to Norman victory, unlike Cranach’s “Paradise” in which the scenes are distributed aesthetically over a canvas.

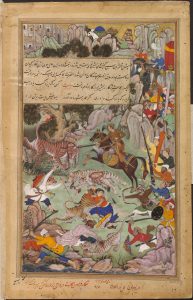

This painting celebrates the Mughal Emperor Akbar and is by Basawan and Tara the Elder (1590). The story (from top-to-bottom, sweeping from side-to-side) depicts the royal entourage attacked by a tiger, protecting her cubs. The panicked entourage froze or hid, but Akbar felled the tiger with a single sword blow. His entourage, recovering their wits, then fought the (very large!) cubs and slayed them. The story was also preserved in words for those who could read, or to be read to those who could not.

This painting celebrates the Mughal Emperor Akbar and is by Basawan and Tara the Elder (1590). The story (from top-to-bottom, sweeping from side-to-side) depicts the royal entourage attacked by a tiger, protecting her cubs. The panicked entourage froze or hid, but Akbar felled the tiger with a single sword blow. His entourage, recovering their wits, then fought the (very large!) cubs and slayed them. The story was also preserved in words for those who could read, or to be read to those who could not.

These images are all wonderful in revealing something about the interaction between the emotional, sensory and historical impact of a story. These images all hold the whole story in one plane, although our emotions and senses may react by unpeeling overlaid layers of meanings. Unlike the supposedly ‘linear’ narratives that we are so familiar at our own particular point in time and space (I am in Ireland, 2018), they allow layers to be drawn on, unpeeled and interpreted in whichever order the viewer accesses, or chooses to access, them. The artists’ aesthetic choices in layout and the sequence of overlying imagery may encourage an order, but can not enforce it.

Stories in matter

Human intent, of course, is not the only storied image. This is the baseline of a wall, in limestone blocks (on a former dock warehouse on the Lower Glanmire Road, Cork). This block has been water-worn by the repeated drips from the roof above a missing section of downpipe. The water-worn grooves are the interaction of stories of the water that has dripped, for years or decades, and the layers of stone layed down in the ocean. Without intent, perhaps, we can read a story of the neglect of some areas of the City that were once prosperous, and the social and political changes that followed Irish independence from the UK.

Human intent, of course, is not the only storied image. This is the baseline of a wall, in limestone blocks (on a former dock warehouse on the Lower Glanmire Road, Cork). This block has been water-worn by the repeated drips from the roof above a missing section of downpipe. The water-worn grooves are the interaction of stories of the water that has dripped, for years or decades, and the layers of stone layed down in the ocean. Without intent, perhaps, we can read a story of the neglect of some areas of the City that were once prosperous, and the social and political changes that followed Irish independence from the UK.

Animals too leave stories. The common snail, Helix aspersa, grazes on algae using a tongue-like radula covered in minute, curved teeth. The snail draws the radula back into itself, leaving a small triangular clear patch as it meanders over the surface. It also swings its head from side-side, leaving a lace-like pattern of tiny triangles, over a fine curve that follows the meandering trail. This photograph captures the story of a snail’s night as it meandered up a garden door in Fota Arboretum, grazing over the hinge and growing more sated as it travelled, so the path becomes narrower and narrower as it continues upwards. It finally turned and headed back downwards. There are layers of broader stories about the interaction between cultivation and nature, the wealth that supported an estate with an arboretum, and the social upheaval that has opened up this magnifent place to the people.

Animals too leave stories. The common snail, Helix aspersa, grazes on algae using a tongue-like radula covered in minute, curved teeth. The snail draws the radula back into itself, leaving a small triangular clear patch as it meanders over the surface. It also swings its head from side-side, leaving a lace-like pattern of tiny triangles, over a fine curve that follows the meandering trail. This photograph captures the story of a snail’s night as it meandered up a garden door in Fota Arboretum, grazing over the hinge and growing more sated as it travelled, so the path becomes narrower and narrower as it continues upwards. It finally turned and headed back downwards. There are layers of broader stories about the interaction between cultivation and nature, the wealth that supported an estate with an arboretum, and the social upheaval that has opened up this magnifent place to the people.

This is a railway sleeper, fashioned from flawless, knot-free timber (Waterford Greenway). The bolt-holes for the rail cleats are surrounded by pitted indentations where the timber lay on ballast gravel, with trains thundering over (and flexing this substantial piece of wood). The impressions are so visceral that the weight of the train, the noise and sucking air as it passes, and the smell of burning coal are just on the surface. Moving the railway sleep, revealing its underside, to create railings along the new cycle and walking route are also a testment to the loss of the Victorian Waterford-Dungarvan railway line, the move to personal transportation and changes in industry.

This is a railway sleeper, fashioned from flawless, knot-free timber (Waterford Greenway). The bolt-holes for the rail cleats are surrounded by pitted indentations where the timber lay on ballast gravel, with trains thundering over (and flexing this substantial piece of wood). The impressions are so visceral that the weight of the train, the noise and sucking air as it passes, and the smell of burning coal are just on the surface. Moving the railway sleep, revealing its underside, to create railings along the new cycle and walking route are also a testment to the loss of the Victorian Waterford-Dungarvan railway line, the move to personal transportation and changes in industry.

This step (Shandon, Cork) was presumably flat when first carved out of stone. Years of human footfall have gradually eroded it, into a gentle curve. This happens to be (tada!) the ‘normal distribution’. Some people place their feet on the left, some on the right, most in the middle. It is normal to do one of these things – that is to say the whole of the distribution is ‘normal’, at the edges and in the middle. Here someone has repaired the threshold, cementing a level surface back in and placing a weather-strip over it. Imagine the cold gale (or scent of fresh baking) blowing through an earlier story in this home!

This step (Shandon, Cork) was presumably flat when first carved out of stone. Years of human footfall have gradually eroded it, into a gentle curve. This happens to be (tada!) the ‘normal distribution’. Some people place their feet on the left, some on the right, most in the middle. It is normal to do one of these things – that is to say the whole of the distribution is ‘normal’, at the edges and in the middle. Here someone has repaired the threshold, cementing a level surface back in and placing a weather-strip over it. Imagine the cold gale (or scent of fresh baking) blowing through an earlier story in this home!

The impressions we make are stronger if we constrain our actions, limiting their effect into smaller regions of rock, or wood, or canvas. The Romans built straight, flat, guarded roads as part of their infrastructure to dominate lands in their empire. The stones in this image (at Herculaneum) are to keep unshod or poorly shod, or perhaps dainty, feet above the mud, wet and rot of a functioning city. Gaps between the stones permitted wheeled vehicles or handcarts to pass. The infrastructure was first formed by human intent, and then acted to constrain human intent. If you want your wheels to pass this point, you have to have an axle that conforms to the standard (un-normal) requirement. Failing to be standard will require some heavy lifting. The standard-keeping majority have then impressed their passage over-and-over into wheel-spaced ruts as they align themsleves with the standard-enforcing social pinch-point.

The impressions we make are stronger if we constrain our actions, limiting their effect into smaller regions of rock, or wood, or canvas. The Romans built straight, flat, guarded roads as part of their infrastructure to dominate lands in their empire. The stones in this image (at Herculaneum) are to keep unshod or poorly shod, or perhaps dainty, feet above the mud, wet and rot of a functioning city. Gaps between the stones permitted wheeled vehicles or handcarts to pass. The infrastructure was first formed by human intent, and then acted to constrain human intent. If you want your wheels to pass this point, you have to have an axle that conforms to the standard (un-normal) requirement. Failing to be standard will require some heavy lifting. The standard-keeping majority have then impressed their passage over-and-over into wheel-spaced ruts as they align themsleves with the standard-enforcing social pinch-point.

Even simple actions, repeated enough times, leave a mark. A right-handed person, using the same (or at least same design) of teaspoon to stir the same mug leaves a mark of metal on stoneware. The availability of mug and spoon, interacting with the natural inclination of a right-handed tea-drinker, constrains these marks to the same locus, repeated daily.

Even simple actions, repeated enough times, leave a mark. A right-handed person, using the same (or at least same design) of teaspoon to stir the same mug leaves a mark of metal on stoneware. The availability of mug and spoon, interacting with the natural inclination of a right-handed tea-drinker, constrains these marks to the same locus, repeated daily.

Left to themselves, humans tend to cluster somewhat less than in standardized grooves and more than merely chaotically. Our physical shape and the energy required by motion direct us into paths that feel easy, sometimes reinforced by the added ease of following one (or a generation) of trail-blazers. This trail has been literally blazed by human desire-lines, avoiding the concrete steps enclosed in concrete walls at Mahon Point Shopping Centre, but spilling somewhat less than freely over the already-trodden path of predecessors.

Left to themselves, humans tend to cluster somewhat less than in standardized grooves and more than merely chaotically. Our physical shape and the energy required by motion direct us into paths that feel easy, sometimes reinforced by the added ease of following one (or a generation) of trail-blazers. This trail has been literally blazed by human desire-lines, avoiding the concrete steps enclosed in concrete walls at Mahon Point Shopping Centre, but spilling somewhat less than freely over the already-trodden path of predecessors.

Impressing intensity

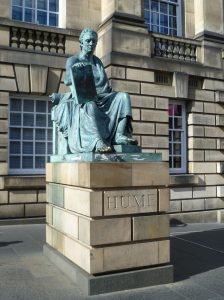

The unconscious repetition of ritual is ingrained here in metal sculptures. The statue of Saint Peter at San Pedro de Alcantara, Spain, displays the stigma of countless devotees who have taken a blessing from his feet. The statue of the humanist David Hume on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh has likewise been marked by students seeking unhumanist luck before examinations, and countless tourists following their example.

The unconscious repetition of ritual is ingrained here in metal sculptures. The statue of Saint Peter at San Pedro de Alcantara, Spain, displays the stigma of countless devotees who have taken a blessing from his feet. The statue of the humanist David Hume on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh has likewise been marked by students seeking unhumanist luck before examinations, and countless tourists following their example.

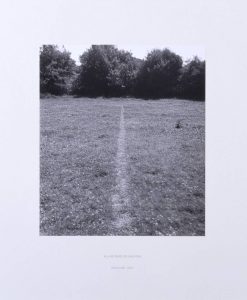

Sara Baume, in her second book, “A Line Made by Walking” (2017), describes this path – straight, unwaveringly undesire-line-like – in “Works about Lower, Slower Views, I test myself: Richard Long, A Line Made by Walking, 1967. A short, straight track worn by footsteps back and forth through an expanse of grass. Long doesn’t like to interfere with the landscapes through which he walks, but sometimes he builds sculptures from materials supplied by chance. Then he leaves them behind to fall apart. He specialises in barely-there art. Pieces which take up as little space in the world as possible. And which do as little damage.”

Sara Baume, in her second book, “A Line Made by Walking” (2017), describes this path – straight, unwaveringly undesire-line-like – in “Works about Lower, Slower Views, I test myself: Richard Long, A Line Made by Walking, 1967. A short, straight track worn by footsteps back and forth through an expanse of grass. Long doesn’t like to interfere with the landscapes through which he walks, but sometimes he builds sculptures from materials supplied by chance. Then he leaves them behind to fall apart. He specialises in barely-there art. Pieces which take up as little space in the world as possible. And which do as little damage.”

Sara Baume’s first book, “Spill Simmer Falter Wither” (2016) is the most beautifully evocative descriptions of the aloneness of what might be autism in 57-year-old Ray’s magical connection with the natural and synthetic environment of Whitegate, Cork. As book that contains emotion and senses within story, this is the best autistic fiction I have read, although that may not have been Sara Baume’s writing of Ray so much as my reading of Ray. See this review in The Atlantic for further information: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/03/spill-simmer-falter-wither-sara-baume-literary-surprise/472698/

Seeing and looking

The Russian psychologist Alfred Yarbus pioneered research on eye-tracking, describing how our eyes make multiple, rapid passes over a scene to determine what is threatening, useful, meaningful or attractive (1967). This image is composed by tracking the eyes of adults viewing Repin’s painting “The Visitor”. People are drawn to the faces in the painting, and somewhat to the hands. They are also drawn to the raised left foot of the visitor, which serves to convey the artist’s construction of this particular image. What we see and what we look at are different things, and neither is equivalent to what we are conscious of seeing or looking at. Autism is in part a difference in the way people see, look at and are affected by the world, particularly the social world.

The Russian psychologist Alfred Yarbus pioneered research on eye-tracking, describing how our eyes make multiple, rapid passes over a scene to determine what is threatening, useful, meaningful or attractive (1967). This image is composed by tracking the eyes of adults viewing Repin’s painting “The Visitor”. People are drawn to the faces in the painting, and somewhat to the hands. They are also drawn to the raised left foot of the visitor, which serves to convey the artist’s construction of this particular image. What we see and what we look at are different things, and neither is equivalent to what we are conscious of seeing or looking at. Autism is in part a difference in the way people see, look at and are affected by the world, particularly the social world.

Different kinds of camera, different kinds of seeing and looking

We tend to assume that “the camera never lies”, but most hand-held cameras and camera films are designed precisely for the purpose of lying. They flatter European skin tones and hair colour, preserve the ‘feel’ of holiday blue skies and blur skin defects. Camera and film makers poorly serve people with very dark or very pale skin, or live on snow or sand, or have a very rainy climate. Kodachrome is obviously biased towards a particular feel, to the extent that modern smart phones often have filters to distort colours to match the Kodachrome look. We might be disappointed by the images captured by a standards-compliant measurement camera, although they do exist for scientific work where colour accuracy is more important than culturally-biased flattery.

Cameras also capture an instant in time, chosen by the photographer to convey the story they wish to tell about the events that are partly contained in the image. They also choose the angle, lighting and framing to include or exclude their selection of story elements.

What is the camera were designed to capture a whole story? A camera actually captures a brief period of time and is not instantaneous. Leaving the shutter open for longer causes the image to blur, unless the camera is fixed to a tripod or other support. A long exposure will then capture static images crisply and blur anything that moves. The image is a statistical average of the light intensity over the whole of the time the shutter is open. Exposing the fish stalls in the English Market, Cork, for just over a minute creates a pleasing sense of the light and space, even the smell of fish and the wetness of the air. The people evaporate into clouds of colour wherever they were standing, walking and choosing fish. A long exposure like this is an unweighted average of the light intensity – all light, moving or static, brief or continuous, are treated equally. Like Schroedinger’s cat, this picture is a story of the location of people over a span of time, rather than the instant. If you reached out and touched a part of the cloud, the probablity of touching a person would be proportional to the intensity of their image at that point.

What is the camera were designed to capture a whole story? A camera actually captures a brief period of time and is not instantaneous. Leaving the shutter open for longer causes the image to blur, unless the camera is fixed to a tripod or other support. A long exposure will then capture static images crisply and blur anything that moves. The image is a statistical average of the light intensity over the whole of the time the shutter is open. Exposing the fish stalls in the English Market, Cork, for just over a minute creates a pleasing sense of the light and space, even the smell of fish and the wetness of the air. The people evaporate into clouds of colour wherever they were standing, walking and choosing fish. A long exposure like this is an unweighted average of the light intensity – all light, moving or static, brief or continuous, are treated equally. Like Schroedinger’s cat, this picture is a story of the location of people over a span of time, rather than the instant. If you reached out and touched a part of the cloud, the probablity of touching a person would be proportional to the intensity of their image at that point.

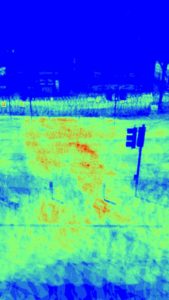

A camera can exploit long exposures to tell and re-tell stories in different ways. To look at the busy junction between Grand Parade and Washington Street, Cork, necessitates looking at the people and traffic using it. Unless the exposure is so long that they evaporate out of perception. This is a nearly two minute exposure on a busy Saturday at midday. The camera could equally be motion-weighted instead of unweighted – the second image overlays only the parts that change, every 1/3 second, over the same two minutes. The 1/3 second was a choice that neatly separated exposures of people and a motorbike as they moved, and could have been much closer together or further apart. Like the cheetah running, or the hands, or the animals in Chauvet, they are different ways of telling a story about the juntion that is very different from a static traditional photograph.

A camera can exploit long exposures to tell and re-tell stories in different ways. To look at the busy junction between Grand Parade and Washington Street, Cork, necessitates looking at the people and traffic using it. Unless the exposure is so long that they evaporate out of perception. This is a nearly two minute exposure on a busy Saturday at midday. The camera could equally be motion-weighted instead of unweighted – the second image overlays only the parts that change, every 1/3 second, over the same two minutes. The 1/3 second was a choice that neatly separated exposures of people and a motorbike as they moved, and could have been much closer together or further apart. Like the cheetah running, or the hands, or the animals in Chauvet, they are different ways of telling a story about the juntion that is very different from a static traditional photograph.

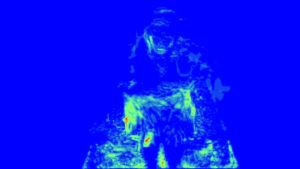

There is a strong relationship between the second image and autism, especially the attention aspects of autism. We are drawn to motion. Our eyes have packed colour-sensitive receptors in the middle of the retina and less packed, but motion-sensitive, receptors at the periphery. Triggering these receptors encourages the brain to look to the action. We can become very good at disregarding this input, especially when we feel safe. Autistic people are less able to disregard the irrelevant stimulus of everyday life. Noises, odour, movement and flickering lights are all consciously processed and have to be actively discarded after evaluation. Like the meditation exercise of “don’t think of an elephant”, it can be very hard not to unthink what we have seen, not to actively look at what we see, to be conscious only of the relevant stimuli that people around us hold in common. Designing a camera that responds, like pre-conscious sight, makes another story of this junction, which I have chosen to colour from blue (where there is little change) to red (where the light intensity changes a lot, or frequently).

There is a strong relationship between the second image and autism, especially the attention aspects of autism. We are drawn to motion. Our eyes have packed colour-sensitive receptors in the middle of the retina and less packed, but motion-sensitive, receptors at the periphery. Triggering these receptors encourages the brain to look to the action. We can become very good at disregarding this input, especially when we feel safe. Autistic people are less able to disregard the irrelevant stimulus of everyday life. Noises, odour, movement and flickering lights are all consciously processed and have to be actively discarded after evaluation. Like the meditation exercise of “don’t think of an elephant”, it can be very hard not to unthink what we have seen, not to actively look at what we see, to be conscious only of the relevant stimuli that people around us hold in common. Designing a camera that responds, like pre-conscious sight, makes another story of this junction, which I have chosen to colour from blue (where there is little change) to red (where the light intensity changes a lot, or frequently).

The second image might be called a heatmap, showing footfall or traffic intensity. It also shows desire lines – people do not approach the pedestrian crossing, stop, turn at right angles and wait patiently to cross. They take paths of least resistance and least energy, crossing in curves and at angles that flow from their origin to their destination. They avoid obstacles like street furniture and other desire lines. They impatiently cross at a diagonal if they are late to the crossing signal. The urban design does not support these desire lines, which don’t map onto the urban grid. Some of the street furniture and safety infrastructure is badly placed on the heatmap, which shows how people do use their environment, as opposed to how they are intended to use it. Their story and the architect’s are at odds. The road’s history as a water-filled shipping channel is also at odds with its present use, even though it influences the current geography.

The second image might be called a heatmap, showing footfall or traffic intensity. It also shows desire lines – people do not approach the pedestrian crossing, stop, turn at right angles and wait patiently to cross. They take paths of least resistance and least energy, crossing in curves and at angles that flow from their origin to their destination. They avoid obstacles like street furniture and other desire lines. They impatiently cross at a diagonal if they are late to the crossing signal. The urban design does not support these desire lines, which don’t map onto the urban grid. Some of the street furniture and safety infrastructure is badly placed on the heatmap, which shows how people do use their environment, as opposed to how they are intended to use it. Their story and the architect’s are at odds. The road’s history as a water-filled shipping channel is also at odds with its present use, even though it influences the current geography.

If we placed this motion-averaging camera in a classroom it might produce a very interesting story of a child’s eye view of learning. We are drawn to action, not importance. We have windows, doors, other people, unintended motion of unfixed objects (posters in the breeze, lamps swinging, floors that squeak) all of which change a child’s conscious perception of learning. Morwenna Banks played the Little Girl, explaining those self-evident truths that we forget as we grow up in the comedy series “Absolutely” (1989-), such as where babies come from, what the Queen is or what school is for. In one episode she is sitting on a table explaining ‘family’, while swinging her legs, patting her knees and touching her ear. The heatmap shows the draw of these movements for the eye. The comedy sketch can be seen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qOStl6rk12o.

If we placed this motion-averaging camera in a classroom it might produce a very interesting story of a child’s eye view of learning. We are drawn to action, not importance. We have windows, doors, other people, unintended motion of unfixed objects (posters in the breeze, lamps swinging, floors that squeak) all of which change a child’s conscious perception of learning. Morwenna Banks played the Little Girl, explaining those self-evident truths that we forget as we grow up in the comedy series “Absolutely” (1989-), such as where babies come from, what the Queen is or what school is for. In one episode she is sitting on a table explaining ‘family’, while swinging her legs, patting her knees and touching her ear. The heatmap shows the draw of these movements for the eye. The comedy sketch can be seen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qOStl6rk12o.

(As an aside, there are other kinds of camera that can capture the motion of an event, or a whole cinema film, and present it as a still image. A slit camera – sometimes used to identify race winners – stores only the narrow central strip of the image, continuously adding copies of it to the end as it changes in time. A bus on Parliament Bridge, Cork, leaves its impression on a vertical strip as it passes a vertical slit camera (looking very much like a bus, as this captured its direction of motion, against the horizontal stripes of the unchanging background), or on a horizontal strip (looking quite unlike buses as we generally know them, against the vertical stripes left by an unchanging road surface).

(As an aside, there are other kinds of camera that can capture the motion of an event, or a whole cinema film, and present it as a still image. A slit camera – sometimes used to identify race winners – stores only the narrow central strip of the image, continuously adding copies of it to the end as it changes in time. A bus on Parliament Bridge, Cork, leaves its impression on a vertical strip as it passes a vertical slit camera (looking very much like a bus, as this captured its direction of motion, against the horizontal stripes of the unchanging background), or on a horizontal strip (looking quite unlike buses as we generally know them, against the vertical stripes left by an unchanging road surface).

Capturing the entirety of a cinema film on a slit camera creates a “movie barcode”, and interesting summary of colour and light intensity that contains so much information that it is almost possible to tell the genre, style or even director from the barcode alone.

We can make an image that looks like a bus in motion – and like images some artists draw of motion – by dragging the slit from top-to-bottom, distorting the bus because the wheels are drawn later, and further forward, than the roof, just like a speeding vehicle. Or we can drag the slit from right-to-left, elongating the length of the bus as the rear is drawn earlier, and further behind, then the front, with the bus now curving along its path like a living thing.)

We can make an image that looks like a bus in motion – and like images some artists draw of motion – by dragging the slit from top-to-bottom, distorting the bus because the wheels are drawn later, and further forward, than the roof, just like a speeding vehicle. Or we can drag the slit from right-to-left, elongating the length of the bus as the rear is drawn earlier, and further behind, then the front, with the bus now curving along its path like a living thing.)

Intentional stories

Intentional stories

This final image a meditational labyrinth in the graveyard of St Finn Barr’s Cathedral, Cork. Visitors can walk the labyrinth from periphery to centre and back again, whilst reflecting. There is only one path, although there must be an almost uncountable number of stories that could be laid out along its path. It is also non-linear and (unlike mazes) the whole path is visible from all points, each accessible in consciousness at the same time, wherever you stand.