I presented a visual essay at the International Union of Archicts (UIA) World Congress of Architects in Copenhagen, 2023. The full paper is available in the proceedings with an open access preprint. If this essay interests you, then you may also be interested in my chapter on “Sensory Issues and Social Inclusion” in the book “Knowing Why: Adult-Diagnosed Autistic People on Life and Autism” published by the Autism Self Advocacy Network (ASAN).

My slides and speaking notes from the session “Design for Inclusivity: Neurodiversity” are below.

I am grateful to Dublin City University and to the Crawford Art Gallery Cork City for their assistance in producing the video material I used to make these images. I am especially grateful to Magda Mostafa for her endless encouragement and the time she spends seeking out and listening to autistic people.

I am an autistic health statistician, a writer and an image-maker. I live in Cork city in Ireland. I make pictures to try to explain my experiences of public places. Today I am displaying images I have made in two places in Ireland. The Crawford Art Gallery in Cork City is a 19th century building in a busy city centre. Dublin City University is a modern pedestrian campus. I am going to briefly outline my motivation for creating these images. You can read more about my methods in the congress proceedings.

I hope my images communicate my experiences of these places. Communication is a two-way process, and must be an ongoing process – as well as sharing images, I want to hear how autistic and non-autistic people respond to my images.

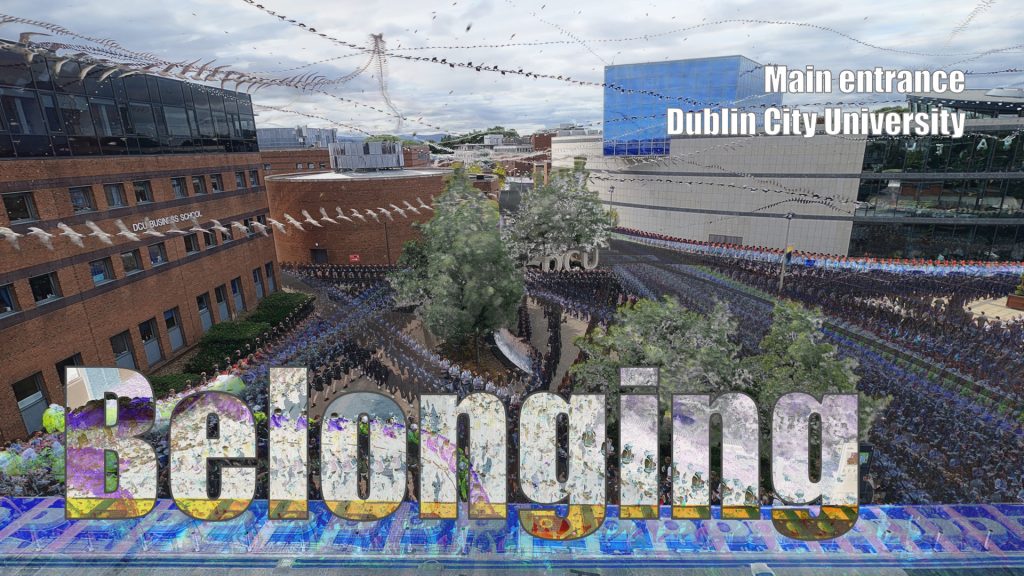

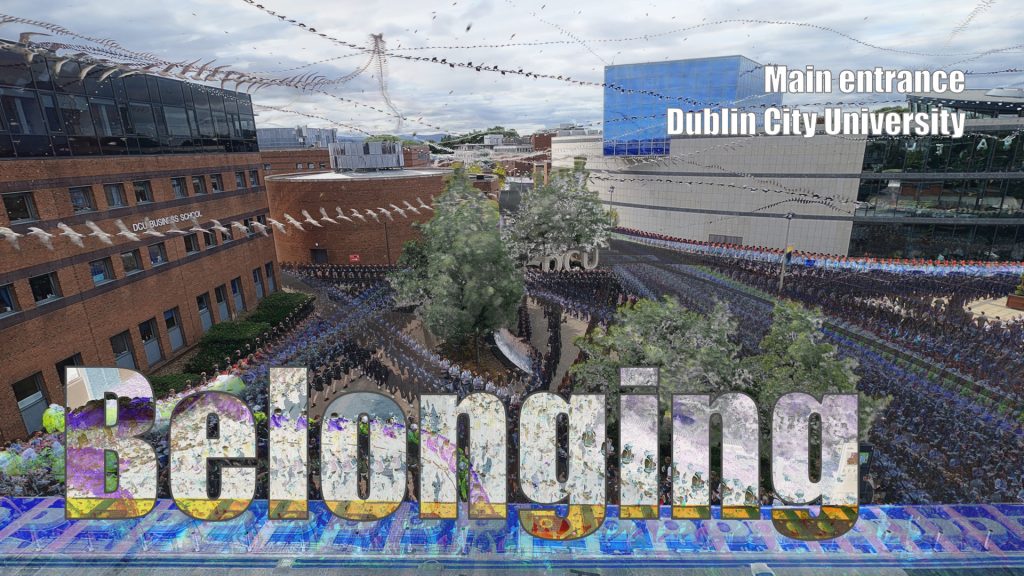

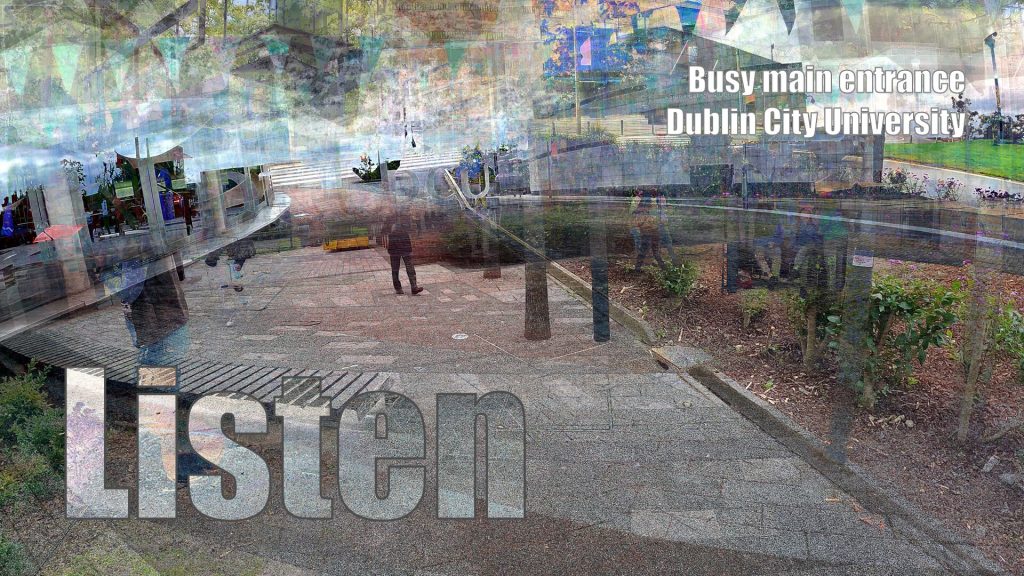

I wonder where I should place myself when faced with all the movement through this busy main entrance to Dublin City University.

Other people seem to navigate public spaces effortlessly, without paying any attention to their features. I am constantly distracted by noise, flicker, moving objects and design features that might (or might not) be significant – for instance a change in font or a change in colour. I am constantly trying to identify where I should place myself, and which paths to take through a place to avoid conflict with other people’s movement, and to avoid close social proximity. I feel a sense of not belonging, in contrast to the vast majority of people who appear to find public spaces welcoming.

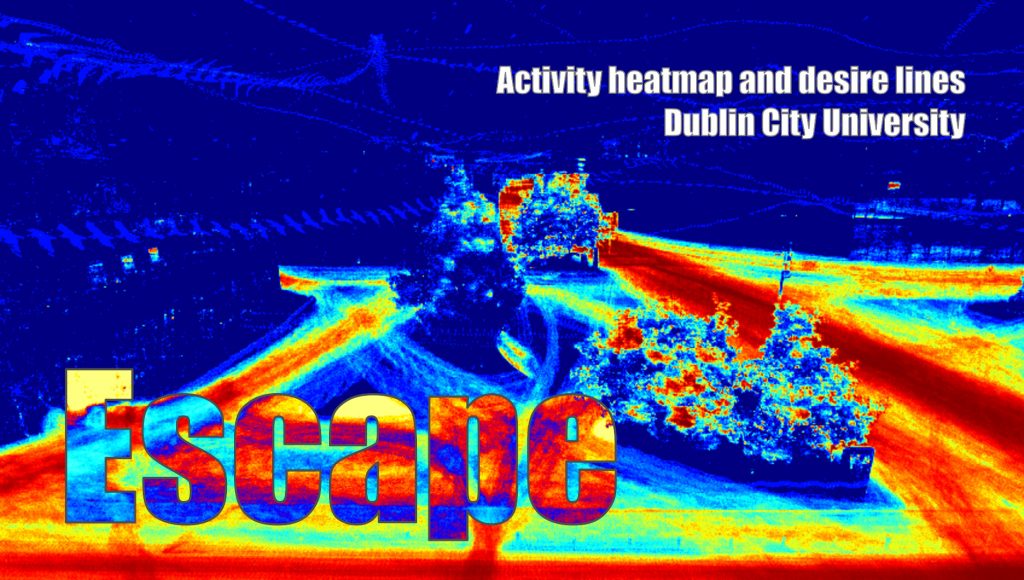

This image uses video processing to expose the network of the busiest desire lines through Dublin City University.

Public places are hard for me to use. Like many autistic people, my executive function limits my ability to plan and sequence activities, or to recover from unexpected change – for instance roadworks closing my path, or a product that is not in stock in the shop. My working memory limits how many steps I can plan and remember to do, unless they are already laid out in a sequence that I can recognise and follow. I experience social anxiety in crowded places. I experience sensory overload from sound, visual change and odour, and I need to find sensory escapes. I feel disabled by design. My image-making is a form of self-soothing, and a way for me to understand and remember my environment.

Images are only one way of representing the experience of public space.

In this composite image I am attempting to represent the sensory and social impact of walking through the busy main entrance to campus. The path ahead is busy, cluttered and anxiety-provoking. It is impossible to avoid meeting people head-on.

Other people might represent their experiences in song, poetry, autobiography, and audio or video documentaries. We should attend to these representations of sensory experiences in whatever medium people feel comfortable to portray their world. We should listen to their needs in their own language, and through dialogue try to determine whether we have understood what they are attempting to communicate.

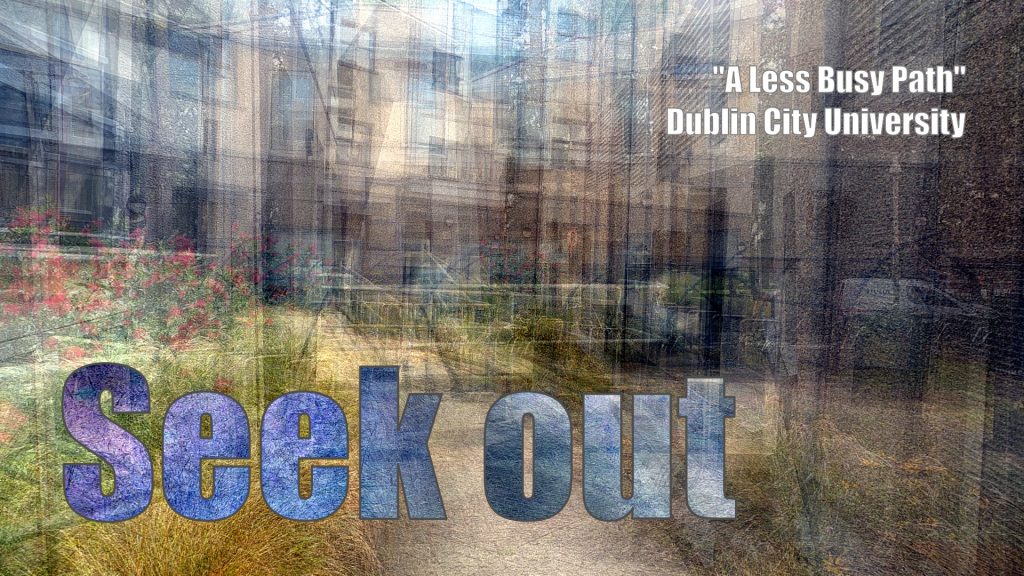

I have used photographs, audio, and video recordings of public places for several years to illustrate my lectures about sensory issues and social inclusion of autistic people. I did not think of these images as related to architecture, until I was guided to recognise them in that way. My image-making has progressed to representations of public space, and I am here today with these images, because Magda Mostafa has actively sought out voices of autistic and neurodivergent people.This, for instance, is a less busy path identified by autistic students for a sensory friendly intervention. Listening should not be a passive exercise designed to tick boxes to report that all the relevant stakeholders were consulted – like an environmental assessment that excludes the opinions of wildlife. We need to actively seek out and actively listen in this dialogue.

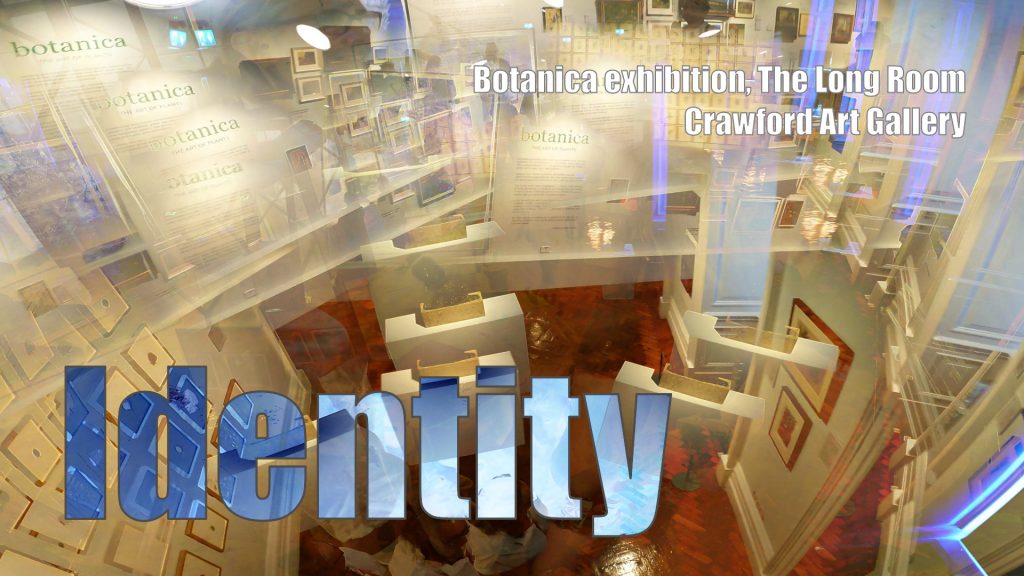

This is a recent exhibition in the Crawford Art Gallery. Some of the artworks are on spindly pedestals. The gallery space is both enticing and scarily precarious, but both we and the artwork are made safe by conscious direction of footfall through the exhibition.

Humans are neurodiverse. There is a wide range of anxiety, executive function, working memory and sensory sensitivity in the population. All of these affect our ability to function, and fluctuate over time and in response to stress and demand. Neurodivergent people sometimes can not identify the affordances in our environment, or exploit the opportunities these affordances create. The degree to which we experience sensory overload, social proximity, sequencing demands and insecurity are all design choices. Much of the world I experience contains design choices that magnify inequality and magnify social exclusion.

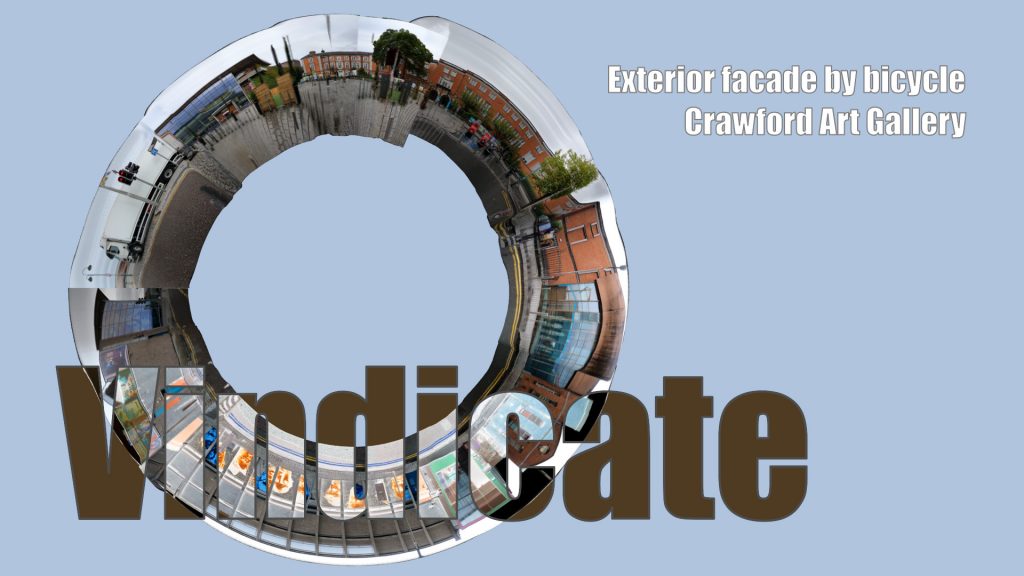

There is only one entrance to the gallery, through a heavy wood and glass door, closely observed by a security staff booth. The anxiety-provoking entry is worth the challenge in order to enjoy the sanctuary from the busy city that exists inside the gallery.

This image is a circuit by bicycle of the perimeter of the Crawford Art Gallery. The building has a forbidding exterior with only one entrance through a heavy door, and a security desk. I feel anxious navigating from the busy city streets to the inner refuge, but in this case I feel the benefits are worth the discomfort caused by its design.

Human rights only exist when they are recognised and upheld by people with the power and the energy to vindicate them. Disabled people are often asked not only to outline their needs, but also to design the solutions that enable their own access to education, work and social inclusion. This is a constant load, like having a second job. People with the technical skills, experience and decision-making power must vindicate disabled people’s rights to inclusion.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we need to:

- Ensure that everyone belongs, somewhere. This does not mean every space must cater equally for every divergent individual.

- Public spaces should include safe escape spaces and connected escape networks, so people can navigate between refuges.

- We need to seek out the full range of (neuro)diversity in society and

- Listen to (neuro)divergent experiences of public space.

- Active seeking and active listening require an ongoing dialogue and communication.

- We must vindicate the rights of all people to inclusion in education, work, leisure and social life.

Side note – further opportunities

Most of the images I use are made outdoors, either in a public place or in a place open to the public, with explicit permission to video. My own negative experiences in education, health settings and other areas of life suggest that these places – which are all places where people have a reasonable expectation of privacy – are also well worth studying. I have used a small number of publicly shared educational training videos to look at classrooms, and the sensory load in these videos is very interesting. For instance I processed this Teacher Support and Assessment video into a motion intensity map, showing how much visual attention lies elsewhere than learning or socialising. I have previously posted a full description of this processing.

A pre- and post-intervention analysis of a classroom, hospital lobby or waiting room, or an open plan office would be revealing, if appropriate privacy safeguards were in place.

More information

- You can see more of my images on my exhibition link.

- “Sensory Issues and Social Inclusion” in the book “Knowing Why: Adult-Diagnosed Autistic People on Life and Autism” published by the Autism Self Advocacy Network (ASAN).

- Interview with Stuart Neilson, on the Lived Experience of Asperger’s Syndrome, by Marie Walsh in Lacunae, the International Journal for Lacanian Psychoanalysis.

- I covered closely related issues in my previous post, derived from my presentation at the AsIAm Ireland Conference 2023: “Picturing Inclusivity in Public Spaces“.

- About 8 years ago, I covered a much less focused set of issues, using photography and sound around Cork City, in “Sensory issues in public spaces“. It is interesting for me to reflect on how my representation of space has developed, and the areas – especially sound sensitivity – where it has not progressed.