I love statistics and numerical analysis, a love that many people do not share — statistics is one of quickest ways to halt a dinner conversation. Statistics is a style of argument that is neither right nor wrong, as useful as any other logical process and has a beauty in summarising or visualizing the subjects under examination in ways that allow two or more things to be compared.

I love statistics and numerical analysis, a love that many people do not share — statistics is one of quickest ways to halt a dinner conversation. Statistics is a style of argument that is neither right nor wrong, as useful as any other logical process and has a beauty in summarising or visualizing the subjects under examination in ways that allow two or more things to be compared.

In the case of film, it can be hard to communicate the incredible experience of sitting for an hour or two, absorbed in action, dramatic tension and emotion. Critics reviews and plot summaries (like those on IMDb) are one method of side-by-side comparison, or even more briefly in the star-ratings (e.g. 8.5 out of 10 for “Psycho”). This post describes some numerical and sampling techniques that I use to create single-image summaries of films and books. These images make stunning wall posters and I have had a few printed as big as 30″ by 20″ to display.

The opening image of this post is a sampled summary of the opening episode of Marvel’s The Defenders (Marvel / Netflix, 2017). The episode is just under 52 minutes (3,120 seconds) long. I wanted to create a montage of equally-spaced frames from the beginning to the end of the episode, with 13 frames across the poster (which is large enough to see each frame clearly on a poster). This required 29 rows of images to make a montage close to the proportions 3 by 2, the standard photo proportions for printing. Processing the video to extract a total of 377 (13×29) frames is just over one frame every 8 seconds. The montage as a whole is a systematic sample of the whole episode, displaying one frame for each 8 seconds, or 1 minute and 47 seconds along each row, starting from the opening title in the top-left and ending with the credits in the bottom-right.

It is beautiful to see the character introductions in this single-image summary of the opening episode. Jessica Jones is filmed predominantly in the blue light of dawn or twilight, Luke Cage in orange or red tones with sunlight or incandescent bulbs, Daredevil appears in dark scenes that almost invariably have a red focal point in the background, and Iron Fist in the yellow-green of indoor strip-lighting. Their enemy Alexandra, in contrast, is devoid of hue and her scenes are brightly lit with white clothing and pale backgrounds.

It is beautiful to see the character introductions in this single-image summary of the opening episode. Jessica Jones is filmed predominantly in the blue light of dawn or twilight, Luke Cage in orange or red tones with sunlight or incandescent bulbs, Daredevil appears in dark scenes that almost invariably have a red focal point in the background, and Iron Fist in the yellow-green of indoor strip-lighting. Their enemy Alexandra, in contrast, is devoid of hue and her scenes are brightly lit with white clothing and pale backgrounds.

It is also easy to look at the montage as a whole, the individual frames, or the titles and prompt recall of the feelings and intensity of watching the original episode. Placing two or more of these montages side-by-side is a method of comparing the overall mood and the changing mood of films.

You can extract frames from a DVD using the mplayer command, but only to the nearest number of whole seconds apart: mplayer dvd://1 -vo jpeg -sstep 8 -frames 377 If your jurisdiction permits home copies of DVDs that you own, it may make more sense to create a video file on hard disk (with mplayer) and extract frames from that using the ffmeg command: mplayer -dumpstream dvd://1 -dumpfile title1.mpg ffmpeg -i title1.mpg -vf fps=8.28 "frame%03d.jpg" The montage command, part of the Imagemagick suite, will create the poster from the set of extracted frames: montage "frame*.jpg" -geometry +0+0 -tile 13x "title1-poster.png"

Slit-camera summaries

Another useful technique is to take every frame of a film, extract only the central vertical column of pixels and join these into a new image that represents the film timeline, from start to finish, as seen by a narrow slit centred on the screen. This produces some eerie and wonderful imagery as the camera pans past objects, or objects move across the image. If the object passes smoothly and without rotating or changing shape, the image it leaves is a reasonably faithful representation of itself. Humans and other objects are animated, rotating, moving limbs, changing shape and leaving traces that vary over time with the slit faithfully capturing a kind of motion-trace. The motion-trace does not faithfully recognize the shape we might know. slit-scan cameras are used in judging close finishes in races, as well as in art. This image is taken from one movement by the Dutch gymnast Sanne Wevers during her gold medal-winning routine at the 2016 Rio Olympics. It shows a relatively stationary background and an animated gymnast as she moves past the camera, flips direction and returns.

Another useful technique is to take every frame of a film, extract only the central vertical column of pixels and join these into a new image that represents the film timeline, from start to finish, as seen by a narrow slit centred on the screen. This produces some eerie and wonderful imagery as the camera pans past objects, or objects move across the image. If the object passes smoothly and without rotating or changing shape, the image it leaves is a reasonably faithful representation of itself. Humans and other objects are animated, rotating, moving limbs, changing shape and leaving traces that vary over time with the slit faithfully capturing a kind of motion-trace. The motion-trace does not faithfully recognize the shape we might know. slit-scan cameras are used in judging close finishes in races, as well as in art. This image is taken from one movement by the Dutch gymnast Sanne Wevers during her gold medal-winning routine at the 2016 Rio Olympics. It shows a relatively stationary background and an animated gymnast as she moves past the camera, flips direction and returns.

![]() We can extract a similar slit-camera image from an entire film, even the 2 hours and 28 minutes (about a quarter of a million frames) of Spectre (2015), although the resulting image is 1,080 pixels high and nearly 250,000 wide. Short elements can be interesting, such as the scene shortly after the opening tracking shot over the Mardi Gras parade and into the reception where James Bond (Daniel Craig) kisses Lucia Sciarra (Monica Bellucci) goodbye before stepping into explosive battle on the parapet outside. Compressing the width of the slit-camera image into a useable size creates a “movie barcode” that summarises the changing colour, brightness and variability of a film in a small space.

We can extract a similar slit-camera image from an entire film, even the 2 hours and 28 minutes (about a quarter of a million frames) of Spectre (2015), although the resulting image is 1,080 pixels high and nearly 250,000 wide. Short elements can be interesting, such as the scene shortly after the opening tracking shot over the Mardi Gras parade and into the reception where James Bond (Daniel Craig) kisses Lucia Sciarra (Monica Bellucci) goodbye before stepping into explosive battle on the parapet outside. Compressing the width of the slit-camera image into a useable size creates a “movie barcode” that summarises the changing colour, brightness and variability of a film in a small space.

The opening episode of Marvel’s The Defenders again shows the hues representing the five principal characters as they are introduced, along with smooth or brittle changes in brightness indicating scene changes. A calm sequence of film results in a smooth tone, while action sequences have abrupt variations in brightness. Marvel has also used the intensity of colour as a means of conveying the emotional intensity of the narrative.

Placing a whole group of these barcodes together summarises a group of films and allows some contrast and comparison between their use of light and colour. This image contains 10 film barcode summaries, with the film poster. American Gods (Starz / Amazon Prime, 2017) has clearly delineated, relatively long scenes in blues (prison), red (Bilquis) and greens (driving with Wednesday). Dead Ringers (1988) has intense red (surgery) and blue (nightmare) sequences involving Jeremy Irons’ two characters. Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 (2017) has super-saturated hues of space travel and science-fiction battle. The Handmaid’s Tale (MGM / Hulu, 2017) is coloured by the uniform clothing, with the exception of an intensely blue flashback to the aquarium. It is fascinating to place Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) against the colour remake of http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0155975/ Psycho (1998) by Guy Van Sant, showing the scene-by-scene alignment of the narrative in the two versions of the same film. Rear Window (1954) has many rapid, voyeuristic changes of imagery as Jeff scans across his neighbors’ windows. Strike (The Cuckoo’s Calling and The Silkworm, BBC, 2017) captures the close, gritty atmosphere of the city centre. Wonder Woman (2017), like Guardians of the Galaxy, has super-saturated colours representing the Pacific blue of Themiscyra against the gloom and fiery warfare of the world of men.

Placing a whole group of these barcodes together summarises a group of films and allows some contrast and comparison between their use of light and colour. This image contains 10 film barcode summaries, with the film poster. American Gods (Starz / Amazon Prime, 2017) has clearly delineated, relatively long scenes in blues (prison), red (Bilquis) and greens (driving with Wednesday). Dead Ringers (1988) has intense red (surgery) and blue (nightmare) sequences involving Jeremy Irons’ two characters. Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 (2017) has super-saturated hues of space travel and science-fiction battle. The Handmaid’s Tale (MGM / Hulu, 2017) is coloured by the uniform clothing, with the exception of an intensely blue flashback to the aquarium. It is fascinating to place Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) against the colour remake of http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0155975/ Psycho (1998) by Guy Van Sant, showing the scene-by-scene alignment of the narrative in the two versions of the same film. Rear Window (1954) has many rapid, voyeuristic changes of imagery as Jeff scans across his neighbors’ windows. Strike (The Cuckoo’s Calling and The Silkworm, BBC, 2017) captures the close, gritty atmosphere of the city centre. Wonder Woman (2017), like Guardians of the Galaxy, has super-saturated colours representing the Pacific blue of Themiscyra against the gloom and fiery warfare of the world of men.

You can create film barcodes from extracted frames using a combination of Imagemagick tools. The first line crops (full HD) images to the centre column of pixels, retaining the original height. These are joined into a wide montage and, to make it possible to compare multiple films, resized to postcard aspect ratio: mogrify -crop 1x1080+960+0 "frame*.jpg" montage "frame*.jpg" -geometry +0+0 -tile x1 "barcode.jpg" convert "barcode.jpg" -resize "3000x2000!" "barcode-postcard.jpg"

Visually summarising texts

Wonder Woman (2017) was accompanied by an official novelization by Nancy Holder, which provides an opportunity to look at essentially the same narrative in two different media — a third if anyone can think up some methods for visually summarizing the graphic novels as well.

Wonder Woman (2017) was accompanied by an official novelization by Nancy Holder, which provides an opportunity to look at essentially the same narrative in two different media — a third if anyone can think up some methods for visually summarizing the graphic novels as well.

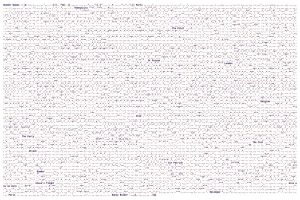

Punctuation is a guide to speed, with fullstops ending a sentence and intermediate punctuation indicating pauses, narrative complexity and (if you feel like it) nested sub-sentences in brackets, clauses separated by hyphens and spoken words in quotation marks. “Machine-gun prose” is a term for the rapid-fire, breathless style of many thrillers and action stories. The image above shows some sequences of rapid prose in Wonder Woman, with slower sequences marked by commas, questions and other forms. The image is annotated with the principal segments of the narrative of the book and film.

Narrative flow and punctuation

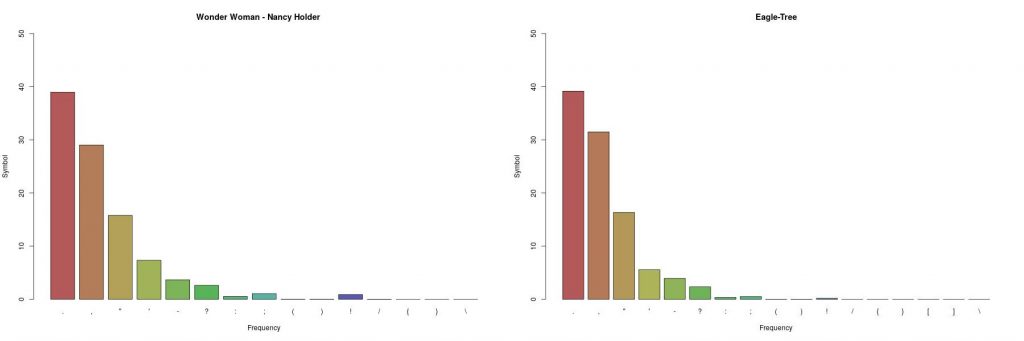

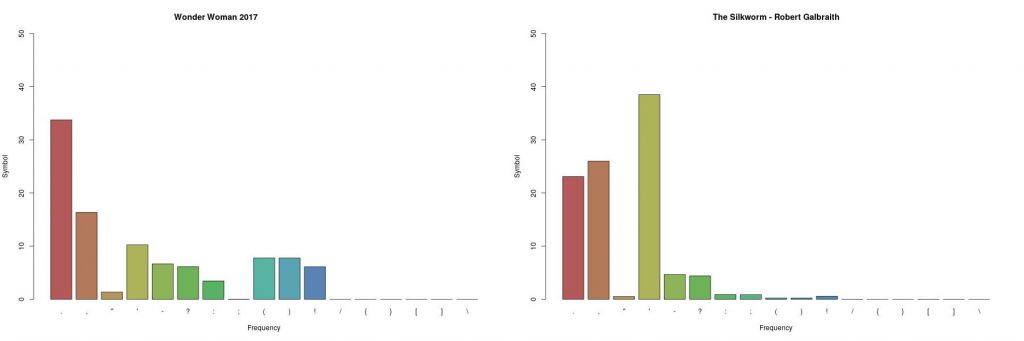

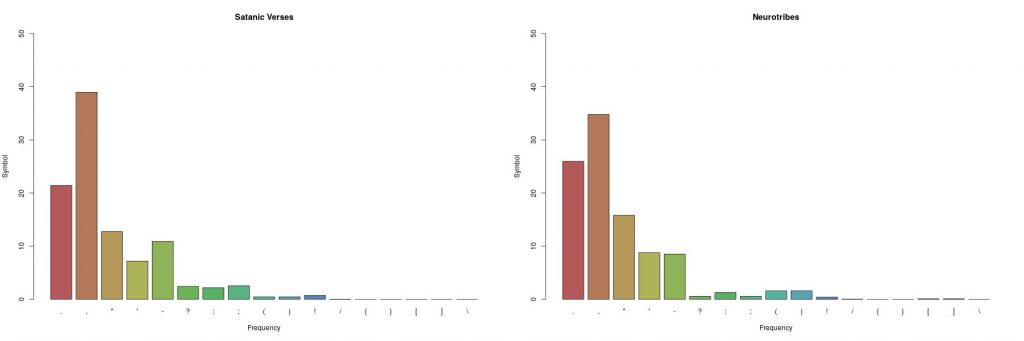

Nancy Holder’s use of punctuation is representative of fiction, as shown against the use of punctuation in The Eagle Tree by Ned Hayes.

Punctuation can be distinctive to a style of prose or even to a specific writer, like a kind of biometric ID. The text of the subtitles to the film Wonder Woman is quite different from the text of the book, because almost all the subtitles represent speech within the events on-screen. In the BBC adaptation of The Silkworm by Robert Galbraith (JK Rowling’s alter ego), a plot element revolves around forensic stylistics of a manuscript supposedly written by “the notorious writer Owen Quine”. His editor says “Now, I’ve edited his stuff for 20-odd years and I never once saw him use a semi-colon. And in that manuscript, there are several. Now, that is not the kind of thing a writer embraces late in his career.” Robert Galbraith also departs from mainstream fiction with more commas than fullstops, indicative of literary writing, and a choice of single rather than double uotation marks for speech. These fingerprints can be enough to classify a text within a specific style of writing, or within the style of a specific author. Variations of forensic stylistics are used to assess authorship attributions and authenticity of documents.

Academic writing is characterized by longer, more complex sentence structures and more variation in punctuation. It is common to cross-reference and note using both round and square parentheses, and to use exclamation marks far less. NeuroTribes by Steve Silberman shows this varied distribution of punctuation, as does much of Salman Rushdie’s magical realism, such as The Satanic Verses.

Semantics and visually extracting themes

It is possible to find several online and offline tools (such as the classic Wordle to create word charts. The frequency of the words in a text give a guide to the topics within the text, especially after extremely frequent stop-words (and, the, etc) have been removed. The image created by word clouds or tag clouds are unigrams, the frequency of single words. Another technique is to count pairs of words that appear in sequence, and graph the most frequent word-pairs.

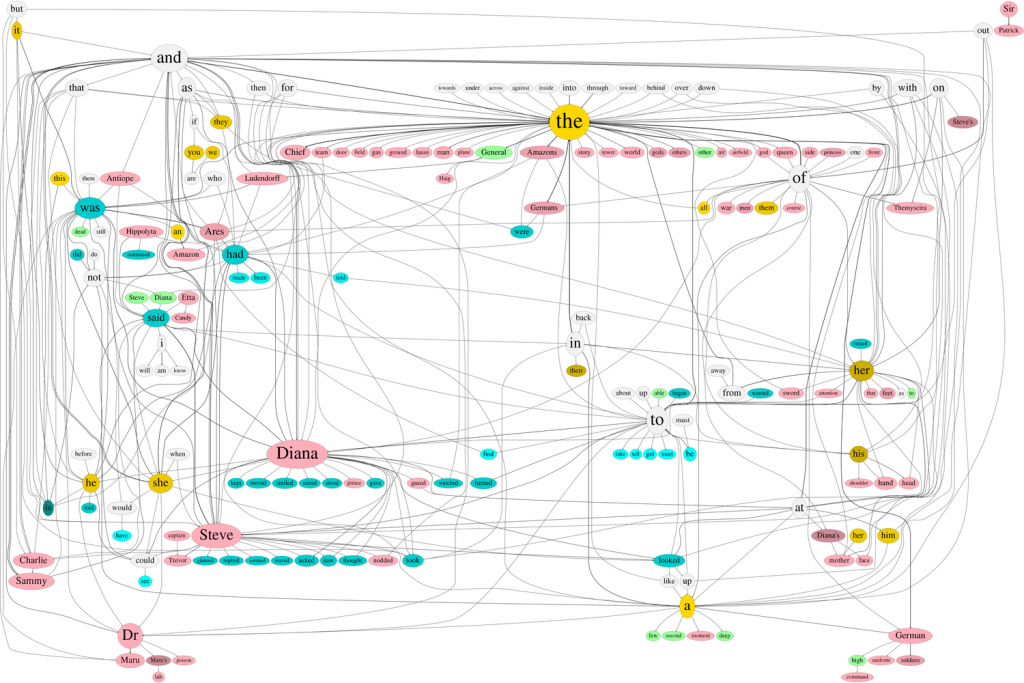

My bigram generator uses the Tagger module of the Perl library Lingua to identify parts of speech — nouns, verbs, adjectives and so on — which would be a monumental task by hand. I have coloured nouns, including proper nouns, in pink. It is easy to locate the principal characters Diana and Steve, which are the most frequent proper nouns in the book and the largest pink ellipses. I use Graphviz to automatically lay out the bigram graph, and Graphviz tries to create the shortest possible links (showing two words that are used together) and the closest packing of words on the page.

My bigram generator uses the Tagger module of the Perl library Lingua to identify parts of speech — nouns, verbs, adjectives and so on — which would be a monumental task by hand. I have coloured nouns, including proper nouns, in pink. It is easy to locate the principal characters Diana and Steve, which are the most frequent proper nouns in the book and the largest pink ellipses. I use Graphviz to automatically lay out the bigram graph, and Graphviz tries to create the shortest possible links (showing two words that are used together) and the closest packing of words on the page.

You can extract a reasonable list of potential proper nouns (characters and places) by descending frequency using a combination of grep, sed and sorting: grep -o "[a-Z] [A-Z][a-Z’’-]*" "book.txt" | sed -e ’s/^[a-Z] //’ | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr

Diana and Steve therefore appear next to each other, simply because the names appear either together or next to words that both are adjacent to. The male characters (Captain Trevor, Charlie, Sammy) and female characters (Antiope, Hippolyta, Etta Candy) tend to cluster in distinct groups. Dr Isabel Maru is strikingly a woman, but isolated from the other gendered characters, in keeping with the depiction of asexuality and disability in the film. Diana and Steve use different verbs (in blue) — Diana kept, moved, smiled, stared, stood, gave and watched; Steve more actively glanced, replied, waved, asked, saw, thought and took. There is a rare use of adjectives (green), which the Perl Tagger has in any case mis-classified on occasion.

I have coloured pronouns in yellow, with some revealing gender associations. His is located with shoulder, hand and head; while her is located with attention, face, feet and (in this book) Mother and sword. This pattern is consistent with the (Male) Gaze, a phenomenon describing power imbalances in constructing film or fiction portrayals. The camera is drawn to the exposure of Diana’s body, available for voyeuristic gratification. Steve is reassuringly muscular, for a hug or a gun.

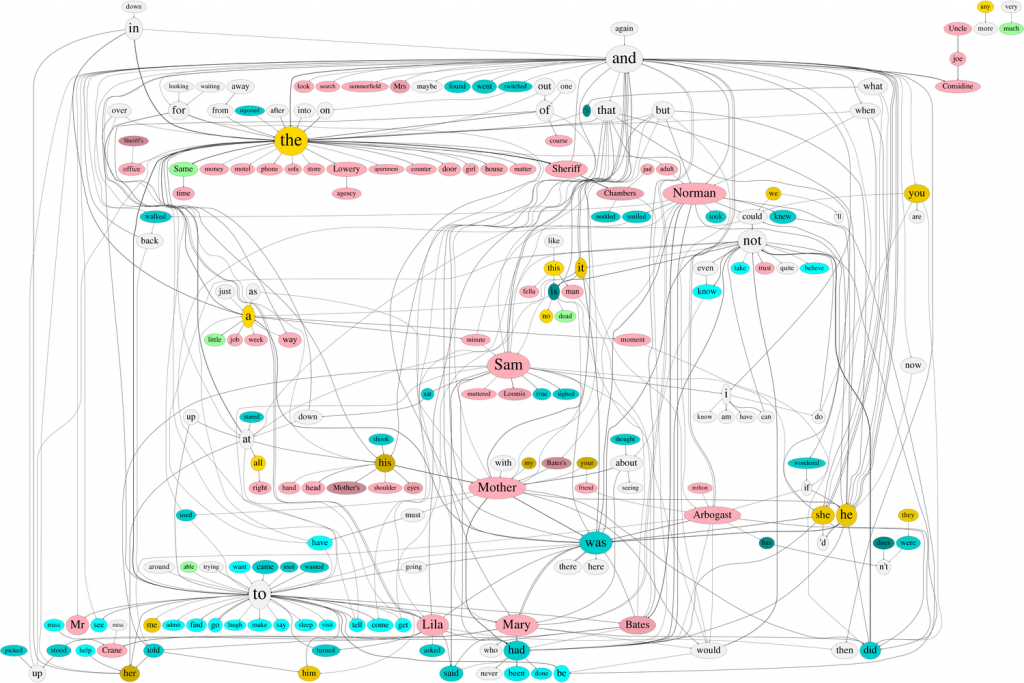

Note that this is repeated pattern across many texts. A bigram graph of the novel Psycho by Robert Bloch places the male characters (Sam Loomis, Sherrif Chambers, Norman) in one cluster, the female characters (Mary, Lila, Mother) in another because these words are linked to the same verbs. Men rose, sighed, nodded, knew and took. Women stood, told, turned, asked. We read about his hand, head, shoulder, eyes and (in Psycho!) Mother.

Note that this is repeated pattern across many texts. A bigram graph of the novel Psycho by Robert Bloch places the male characters (Sam Loomis, Sherrif Chambers, Norman) in one cluster, the female characters (Mary, Lila, Mother) in another because these words are linked to the same verbs. Men rose, sighed, nodded, knew and took. Women stood, told, turned, asked. We read about his hand, head, shoulder, eyes and (in Psycho!) Mother.

Nerdgasm

For me personally, this kind of analysis is a total nerdgasm. I can spend hours immersed in analysis of texts and imagery and find, after the concentration on technique, quite unexpected revelations about the material. In statistics I frequently find myself dissociated from the humanity of the topic, looking at difficult health or social issues purely within a frame of numerical analysis, until I reach the conclusion and start to narrate the meaning within the results. Numerical analyses have a great power to distance from a topic, to allow objective analysis, to compare seemingly different subjects, and then return (often with a crash) to the reality of what, subjectively and emotionally, the outcomes mean.

I have had some of the images above printed out as fabulous 30×20 inch (almost 3 feet tall) photographic posters, and they are stunning. I quite often see something new when I look at them again, as well as having a very evocative reminder of the films themselves.

It is fascinating how different people can manage to bring their own understandings and perspectives to film and fiction. In our film discussion group I am constantly amazed, challenged and forced to rethink by the incredible depth of knowledge and breadth of perspectives that each participant brings to the discussion.

Books, films and tools

- The Eagle Tree by Ned Hayes

- NeuroTribes by Steve Silberman

- Psycho by Robert Bloch

- The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie

- Wonder Woman by Nancy Holder

- IMDb

- American Gods (Starz / Amazon Prime, 2017)

- Dead Ringers (1988)

- Marvel’s The Defenders (Marvel / Netflix, 2017)

- Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 (2017)

- The Handmaid’s Tale (MGM / Hulu, 2017)

- Psycho (1960)

- Psycho (1998)

- Rear Window (1954)

- Strike, The Cuckoo’s Calling & The Silkworm (BBC, 2017)

- Wonder Woman (2017)

- The (Male) Gaze