Urban space is changing fast and despite the potential to increase urban space through growth, technology and social progress, the reality is often increasing exclusion and isolation. My own experience is one of a city increasingly paved over, squared off, noisier and lacking in calm spaces. Traffic, busy people and blank commercial facades have replaced more welcoming districts, because accessibility and family-friendly features are not a developer priority – they maximise borrowings, ramp up local property prices, take the increase in plot value and move on. Sustainable community is not a short-term money-spinner.

My perspective is very much the social exclusion and sensory impact of unsympathetic development. This post includes some images of Cork City and data maps of changing city demographics, at the level of the 74 electoral districts, to outline how the city is changing.

Further reading:

- Department of Housing “Review of Delivery Costs and Viability for Affordable Residential Developments“

- Dubin City Council “Maximising the City’s Potential“, particularly Paul Keogh’s presentation on “Urban Design“

- An Taisce “Building Height Guidelines 2018 Consultation“

- An Taisce “Urban Development and Building Heights Guidelines for Planning Authorities“, particularly section 6.0 on “High Density – Low Rise” development

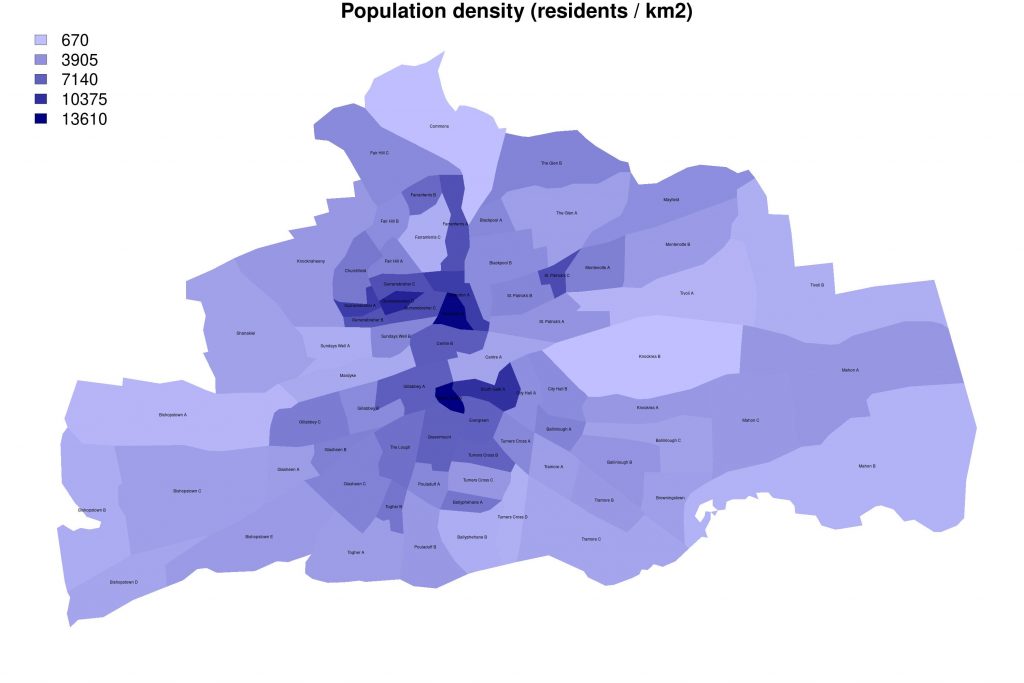

First off, population density and growth are not a bad thing. There is a dire homelessness problem (and Ireland is about the 10th richest in the world). The distribution of high-density housing – greater than 10,000 people per km2 in South Gate, Shandon, Gurranebraher and St Patrick’s – may surprise some people, as these are traditional terraced disctricts rising to 3 or 4 stories. The low-density areas – below 2,000 people per km2 in Knockrea, Commons, Bishopstown, Tivoli and Mahon – may equally surprise. Most city people, most city families and most city children live in higher density dwellings.

In addition, 80% of Ireland’s housing stock is more than 40 years old, built before 1980 and before modern mandatory accessibility, energy and space requirements. Some can be retrofitted and some will never be sufficiently accessible, energy efficient or large enough.

The Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, An Taisce and Dublin City Council all agree that sustainable communities are an essential core of future urban space, and that the optimal height for the delivery of affordable housing is six stories. This is both a human scale at which sensory, accessibility and community connectivity issues are potentially well-addressed, and it is sympathetic with the existing scale of the denser districts of terraced housing within Cork and other Irish cities.

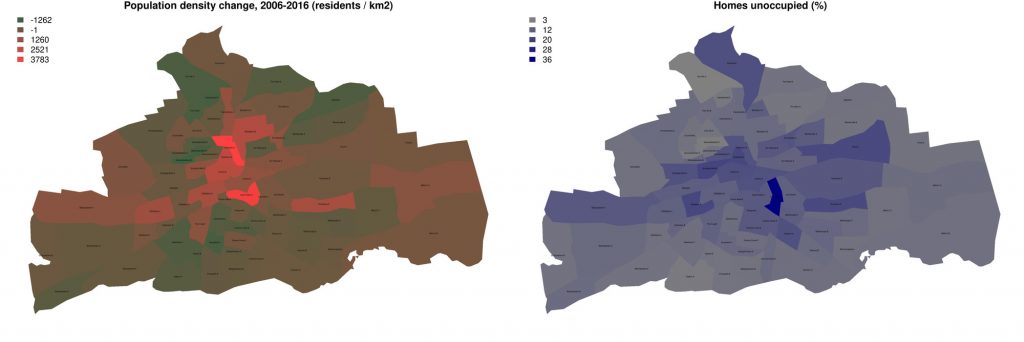

The population of Cork City is currently increasing, following a long period of decline – from 136,000 in 1986 to 119,000 in 2011 and 126,000 now. The current increase disguises the fact that the population is continuing to fall throughout most of the city (in 42 of 74 electoral districts) with increasing numbers of unoccupied and derelict properties. Most shockingly, the proportion of unoccupied completed dwellings is as high as 36% in City Hall and greater than 15% – 1 in every 6 properties – across large parts of the city. Almost 6,000 completed dwellings (only 70 of which are registered as hoilday homes) are unoccupied, and it is not possible to determine how many of these are unaffordable or cuckoo-banked new units.

Growth, concentrated along the river in Bishopstown, Gillabbey, Centre and Tivoli (docks), is overwhelmingly commercial and single-occupancy residential, with a growing emphasis on high-rise buildings. The style of high-rise rising in Cork is much the same, in topology, as a gated estate and is inaccessible to outsiders, unwelcoming to children and hard work for disabled or older people. High-rise (and especially moderate-rise) need not be inaccessible, this is a choice for maximum gain on a site, made by developers with a short-term outlook and interest.

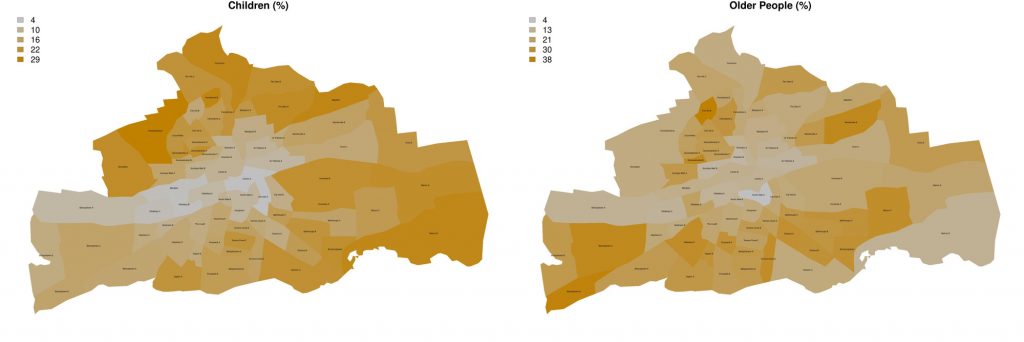

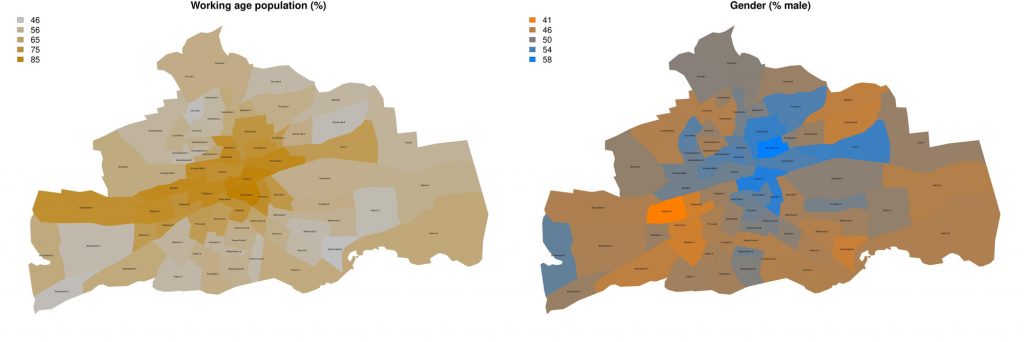

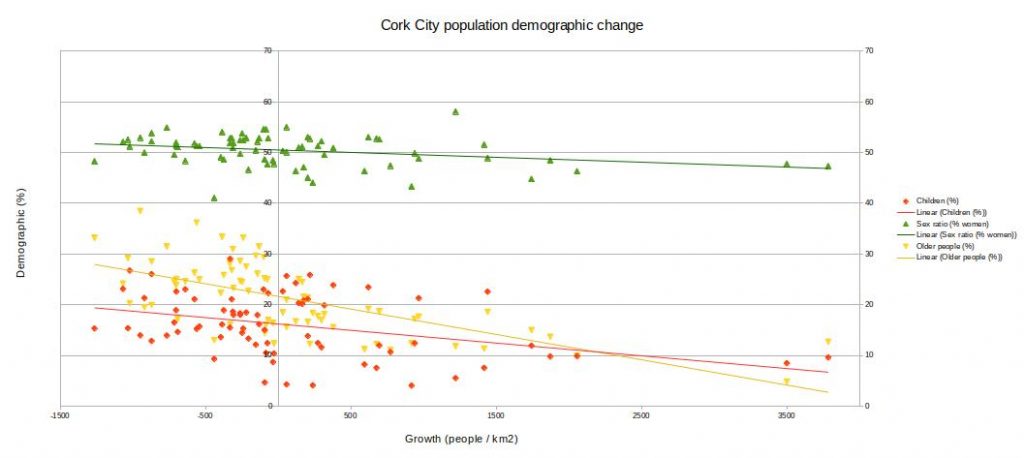

The horizontal growth area has displaced children (0-17 years), older people (60+) and women. The percentage of children and older people has fallen to just 4% in Centre, City Hall, Gillabbey, Mardyke and Bishopstown. Old people are just 4% of the population in South Gate and around 10% of the population in central districts. Where new residential developments have been created, they are largely single occupancy and inaccessible. The proportion of children in the city as a whole is four times higher, 16%, and as high is 29% in remaining traditional community areas. The proportion of older people is 21% in the city overall and up to 38% in sustained community districts.

In stark contrast to the gradual expulsion of families, children and older people from the city centre, the incoming population is largely single, working age (18-59) and more frequently male. The starkest change is in South Gate, which is 87% working age, 48% female and has few children (8%) or older people (5%), but this is reflected across a horizontal band cutting the city in two and dividing individual communities with large, private monoliths.

The gender ratio is as low as 42% (1.4 men to each woman) in Gilabbey and below 45% across several electoral districts. A number of possibilities for the gender difference include lower income of women pricing young single women out of new dwellings, fear of greater insecurity and isolation in apartment structures, less pressure to leave parental homes and greater probability of women being sole parent. Whatever the cause, there is a structural inequality in building dwellings that are not attractive to women in increasingly young, male districts.

A single-image summary of the decline of family-friendly, accessible urban zoning is given above. Most (42 of 74 electoral districts) of the city is in decline, and most children, older people, women and families live in declining areas. The areas in which the population has risen are increasingly working age and more often male.

Accessible space

Most current developments are solid facades with a secure entry to commercial buildings and blocks of single-occupancy units, without internal or external amenity space. Where “space” has been included in a development it is typically pseudo-public private space, lacking in secluded quiet zones and paved as a rapid transit thoroughfare, not as a garden or park. Seating is not designed to encourage loitering, privacy or calm. Open spaces are often within a broad thoroughfare and are not bounded from traffic to contain children, or to separate fast walkers, joggers and cyclists from seating. They are not easy or relaxing places to be.

If we want an accessible, community-centre future city, we need to develop, or include within all developments, family-sized dwellings, disability-accessible dwellings, elderly-accessible dwellings and local amenities that attract and retain community. We need open spaces – and existing spaces are at risk with council describing the Peace Park as “under-utilised space” and proposals to convert the Peace Park into a plaza and thoroughfare serving the Event Centre. We need shops, quiet space, play space and clinics. We need safe routes to navigate between individual dwellings without crossing roads, passing through security gates, negotiating with security staff or irritating busy workers.

As you walk around your own geography, think about how children could play unsupervised, older people read or eat outdoors, wheelchairs or buggies navigate entries and paths, or just lying in the sunshine yourself. What would it be like to raise a child and to grow old where your live?