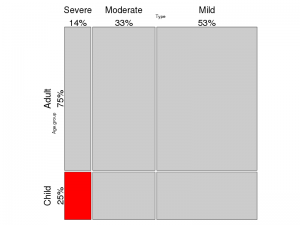

If autism was assumed to affect all people at all ages approximately equally, there are somewhere between 15,000 (1 in 300) and 100,000 (1 in 43) autistic people of all ages in the Irish population of 4.6 million. It should be noted that 75% of the Irish population is older than 18 years and most will not have been assessed or diagnosed, so many autistic people are unrecognized. Recognition is widening from “severe autism in childhood” to “mild autism” and to older ages, which is probably the largest factor driving increased autism prevalence. We have also moved from recognizing approximately one autistic pupil per school to recognizing one autistic child per class in the space of ten or fifteen years.

If autism was assumed to affect all people at all ages approximately equally, there are somewhere between 15,000 (1 in 300) and 100,000 (1 in 43) autistic people of all ages in the Irish population of 4.6 million. It should be noted that 75% of the Irish population is older than 18 years and most will not have been assessed or diagnosed, so many autistic people are unrecognized. Recognition is widening from “severe autism in childhood” to “mild autism” and to older ages, which is probably the largest factor driving increased autism prevalence. We have also moved from recognizing approximately one autistic pupil per school to recognizing one autistic child per class in the space of ten or fifteen years.

The prevalence of autism in Ireland has never been comprehensively assessed, and data collection is one of the aims that will proceed whenever the Autism Bill 2012 completes its passage through the Dáil(see https://asiam.ie/explainer-autism-bill-2012-2 for an explanation of the Bill).

One study in Cork and Kerry screened 2,117 infants for early signs of autism and 7 were ultimately clinically diagnosed, a rate of 0.33% (1 in 300). (Van Den Heuvel et al (2007) Screening for autistic spectrum disorder at the 18-month developmental assessment: a population-based study https://cora.ucc.ie/handle/10468/90). A collaboration between Irish Autism Action and Dublin City University studied 8,138 school pupils in Cork, Galway and Waterford cities. They found a headline prevalence of 1% (1 in 100) in these city school pupils. (‘Autism Counts’ — an Irish Autism Action-funded research project, 17th July, 2013 http://www4.dcu.ie/marketing/staffnews/2013/jul/irishautism.shtml, abstract: http://irishautismaction.newsweaver.com/newsletter/1dqgyva6cjn?a=1&p=48094816&t=22172345, full thesis: http://doras.dcu.ie/view/people/Boilson,_Andrew_Martin.html).

Much larger surveys in the United States and Europe provide good estimates of prevalence in two populations similar to the Irish population.

The most recent large-scale US survey found a school age prevalence of 1.46% (1 in 68). (Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/ss/ss6503a1.htm). The most recent survey in Northern Ireland found a school age prevalence of 2.3% (1 in 43). (Publication of ‘The Prevalence of Autism (including Aspergers Syndrome) in School Age Children in Northern Ireland 2016’ https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/news/publication-prevalence-autism-including-aspergers-syndrome-school-age-children-northern-ireland-2016).

These studies provide a range of somewhere between 15,000 and 100,000 autistic people in Ireland.

The geography of Special Needs (and probably autism)

There is no source of published regional data on autism in Ireland. The NCSE, DES and CSO publish data from 1995 onwards based on the number of mainstream pupils who receive support from Resource Teaching Hours (RTH) or from a Special Needs Assistant, and the number of pupils in Special Schools (http://ncse.ie/statistics). These data are summarised in key statistics each year (Table 6 Number of National School Pupils and Classes Classified by Local Authority Area in 2014-2015 http://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Statistics/Key-Statistics/Key-Statistics-2014-2015.pdf). There is no breakdown by primary need, although the total number of pupils with autism listed as primary need who received Resource Teaching Hours in 2013 was 6,539 (4487 in National School and 2,052 in post-primary school) (Supporting Students with Special Educational Needs in Schools, 2013 http://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Supporting_14_05_13_web.pdf). This is similar to an earlier estimate of 0.56% of school pupils (page 9 of International Review Of The Literature Of Evidence Of Best Practice Provision In The Education Of Persons With Autistic Spectrum Disorders http://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/2_NCSE_Autism.pdf).

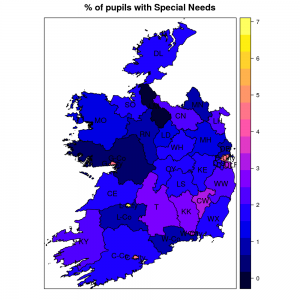

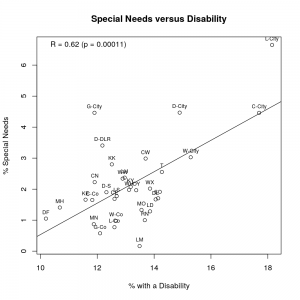

Mapping the total number of pupils with Special Needs support by Local Authority in 2014-2015, that is the sum of pupils receiving Special Needs support in mainstream school and the pupils in Special Schools, there is a marked geographic variation. The highest rate is 6.7% of pupils in Limerick City and the lowest rate is 0.17% of pupils in Leitrim and the — a factor of 40 between the highest and lowest Special Needs provision in Local Authorities.

Mapping the total number of pupils with Special Needs support by Local Authority in 2014-2015, that is the sum of pupils receiving Special Needs support in mainstream school and the pupils in Special Schools, there is a marked geographic variation. The highest rate is 6.7% of pupils in Limerick City and the lowest rate is 0.17% of pupils in Leitrim and the — a factor of 40 between the highest and lowest Special Needs provision in Local Authorities.

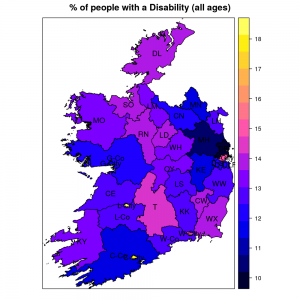

An interesting parallel is the number of people, of all ages, who are disabled according to the 2011 Census results. Most people with a disability are elderly and it seems plausible that some Local Authorities are better resourced than others, and either more likely to assess and recognize disability (and autism), or more attractive as destinations for services, or both. It seems likely that people send their children from low-resource Local Authorities to high-resource Local Authorities and that they may physically relocate in order to access resources. It is also plausible that autism and disability are under-reported in low-resource regions.

An interesting parallel is the number of people, of all ages, who are disabled according to the 2011 Census results. Most people with a disability are elderly and it seems plausible that some Local Authorities are better resourced than others, and either more likely to assess and recognize disability (and autism), or more attractive as destinations for services, or both. It seems likely that people send their children from low-resource Local Authorities to high-resource Local Authorities and that they may physically relocate in order to access resources. It is also plausible that autism and disability are under-reported in low-resource regions.

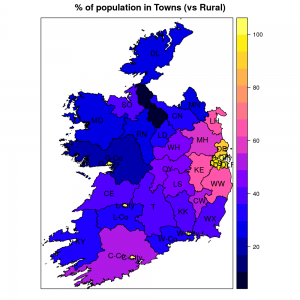

One simple factor affecting the economic viability of resources is size and available population. This is summarized by the CSO census measure of Town and Rural residence — the most rural Local Authority is Leitrim, with just 10.4% of the population living in Town areas. Fewer than 1.5% of National Schools are Special Schools in Cavan, Donegal, Galway County, Laois, Leitrim, Limerick County, Offaly and Roscommon, compared to 4.2% (138 of 3,262) schools nationally. Fewer than 7% of National Schools provide any Special Needs support in Cavan, Donegal, Kilkenny, Leitrim, Roscommon, Sligo and Waterford County, compared to 12.4% (386 of 3,124) of ordinary National Schools. Small schools can not support a specialist post, which in turn drives pupils in needs of resources further from home, which in turn increases resourcing to schools that already provide at least one specialist support post. This appears to also drive multiple disavantages together because specialist posts are more frequent in schools in disadvantaged communities within more populated regions. This may be a good outcome if it is recognized and adequate resources are provided to fund specialist centres, and so long as people in rural areas have access to education. At present it seems that some Local Authorities are not providing adequate supports and other Local Authorities are supporting large Special Needs provision without matching funds.

One simple factor affecting the economic viability of resources is size and available population. This is summarized by the CSO census measure of Town and Rural residence — the most rural Local Authority is Leitrim, with just 10.4% of the population living in Town areas. Fewer than 1.5% of National Schools are Special Schools in Cavan, Donegal, Galway County, Laois, Leitrim, Limerick County, Offaly and Roscommon, compared to 4.2% (138 of 3,262) schools nationally. Fewer than 7% of National Schools provide any Special Needs support in Cavan, Donegal, Kilkenny, Leitrim, Roscommon, Sligo and Waterford County, compared to 12.4% (386 of 3,124) of ordinary National Schools. Small schools can not support a specialist post, which in turn drives pupils in needs of resources further from home, which in turn increases resourcing to schools that already provide at least one specialist support post. This appears to also drive multiple disavantages together because specialist posts are more frequent in schools in disadvantaged communities within more populated regions. This may be a good outcome if it is recognized and adequate resources are provided to fund specialist centres, and so long as people in rural areas have access to education. At present it seems that some Local Authorities are not providing adequate supports and other Local Authorities are supporting large Special Needs provision without matching funds.

The provision of Special Needs resources correlates signicantly with Town dwelling and with population Disability, i.e. Local Authorities with a greater proportion of urban residences report higher levels of Special Needs provision and higher rates of Disability. The underlying rate may include unassessed (and unreported) needs for resources and disability in some Local Authorities, particularly those with large Rural residences.

The provision of Special Needs resources correlates signicantly with Town dwelling and with population Disability, i.e. Local Authorities with a greater proportion of urban residences report higher levels of Special Needs provision and higher rates of Disability. The underlying rate may include unassessed (and unreported) needs for resources and disability in some Local Authorities, particularly those with large Rural residences.

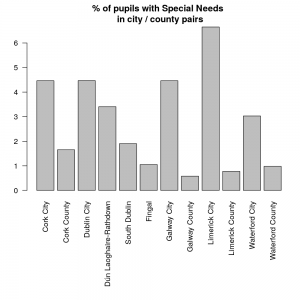

The relationship between Special Needs and urban location is striking when pairing cities with their surrounding counties. Not only is the rate of Special Needs pupils higher in the five largest cities of Cork, Dublin, Galway, Limerick and Waterford, but also they appear to have drawn a disproportionate number of Special Needs pupils from their counties, in which the rate is lower than the national average of 2.2% of National School pupils. The rate is 2.7 times higher in Cork City than Cork County, 3.1 times higher in Waterford City than County, 7.7 times higher in Galway City than County and 8.6 times higher in Limerick City than County. It should be noted that Limerick City lies near the boundary between Limerick and Clare counties, drawing pupils from both. There is a gradient from a high in Dublin City (13.6%), through Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown and South Dublin to a low in Fingal (4.3%).

The relationship between Special Needs and urban location is striking when pairing cities with their surrounding counties. Not only is the rate of Special Needs pupils higher in the five largest cities of Cork, Dublin, Galway, Limerick and Waterford, but also they appear to have drawn a disproportionate number of Special Needs pupils from their counties, in which the rate is lower than the national average of 2.2% of National School pupils. The rate is 2.7 times higher in Cork City than Cork County, 3.1 times higher in Waterford City than County, 7.7 times higher in Galway City than County and 8.6 times higher in Limerick City than County. It should be noted that Limerick City lies near the boundary between Limerick and Clare counties, drawing pupils from both. There is a gradient from a high in Dublin City (13.6%), through Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown and South Dublin to a low in Fingal (4.3%).

“Soft barriers”

It has been stated that some schools, communities and principals erect “soft barriers” to prevent or discourage parents from enrolling children with special needs, identified as an issue by the NCSE in 2013 (Independent, 2013). The majority religious-run secondary schools are more likely to erect “soft barriers” than the minority State schools (RTE, 2016). The Education (Admission to Schools) Bill may end some practices that limit access to schools (Irish Times, 2016).

(Barriers in Ireland include having a sibling at the school, a parent at the school in the past, residence, having attended a specific feeder school, religion, fees and “voluntary contributions”, academic ability, remaining on a lengthy waiting list and others. Many of these barriers are “hard barriers” for Travellers, migrants and families who move to access services).

The 2016 NCSE/ESRI report stated that “Special class provision and provision for students with SEN more generally is also influenced by greater levels of demand for SEN provision in certain school contexts. Some school principals interviewed raised concerns about school admissions policies creating soft barriers to accepting students with SEN and thus concentrating these students in other, often disadvantaged schools. This in turn, principals felt, impacted on the reputation of the school in the community and morale within the school itself.” (page 4, (Special Classes in Irish Schools Phase 2: A Qualitative Study).

The 2013 NCSE report stated that “The most fundamental need of all is that a child can be enrolled in a school. While most schools do welcome and enrol children with special educational needs, the NCSE is disappointed that some schools erect overt and/or ‘soft’ barriers to prevent or discourage parents from enrolling their children in these schools. We consider that schools are funded and resourced to provide an educational service to all children in their locality. Exclusionary practices cannot be permitted in any national system of education.” (page 4) and “The consultation highlighted practices whereby schools place ‘soft’ barriers to enrolment by advising parents that a different school is more ‘suitable’ for their child or has more resources for supporting students with special educational needs. In other examples, schools have refused to enrol a child on the basis that they are not being allocated all the resources, particularly health-funded resources, they consider are required for a particular child. The NCSE is also aware of situations where schools have simply refused to open a special class for a cohort of students, where a need has already been identified, where there is space and where additional resources can be made available.” (page 90, Supporting Students with Special Educational Needs in Schools).

“Dollars for diagnosis” of ADHD and Special Needs labels

Last week (19 November 2016) the head of the NCSE was quoted as saying that parents were shopping for diagnostic labels that enable access to the resources to support their children, “playing the system” for support (Independent, 19 Nov 2016 and Independent, 15 Nov 2016). I doubt anyone would choose to label their child with ADHD if there was adequate support for their child’s learning, and that most “misdiagnosis” is substition of labels that do enable access to resources (ADHD or autism) for labels that provide limited or no resources (dyslexia). It would be far better if schools were resourced adequately to cope with whatever needs a child has, on whatever dimensions, without labelling some as “Special” and without forcing families to seek professional labels for their children.

There is little doubt that motivated, affluent or highly educated families are more able to commit to multiple assessments, pursue private diagnoses and use terminology that affects the final outcome of assessment. Those families are much more able to shop for well-resourced schools. There is no blame attaching to parents who obtain the education their child needs. There is blame attaching to the political and social processes that lead to poor resources, especially over entire Local Authorities in which Special Needs resources are not available.

The impact of resource provision on geography

Over the past two decades there was a substantial growth in Special Needs and dramatic relocation of resources into specific Local Authorities and into the five largest cities. Special Needs included Resource Teaching for Travellers until 2010-2011, when 6,000 Traveller pupils were reclassified and no longer included in Special Needs provision. The concentration of Special Needs provision therefore drops dramatically in 2012, and continues its concentration into the five cities.

Over the past two decades there was a substantial growth in Special Needs and dramatic relocation of resources into specific Local Authorities and into the five largest cities. Special Needs included Resource Teaching for Travellers until 2010-2011, when 6,000 Traveller pupils were reclassified and no longer included in Special Needs provision. The concentration of Special Needs provision therefore drops dramatically in 2012, and continues its concentration into the five cities.

One thought on “The geography of special needs (and autism?) in Ireland”

Comments are closed.