As the prospect grows closer of a continuous cycle and walking route from the Inniscarra Dam to the harbour, this post assesses how many people and schools are within a car-free catchment area around the route. Two boundaries are displayed, a 2 km zone in which most people will be within a 15-minute walk and a 6 km zone in which most people are within a 15-minute cycle ride of the route. The number of post-primary schools and total pupil roll are separately counted.

These figures matter greatly because car park provision will be immediately raised, with the potential to induce additional motorised traffic to and around the route. In reality, large numbers of people, Bed & Breakfast, hostels and restaurants already lie directly on this resource, with large volumes of existing on-street and business parking space.

- The proposed Lee to Sea route provides 46 km of mixed woodland, lake, river and seaside greenway, with an elevation range of just 45 m;

- 157,000 people live within 2 km of the route and 229,000 within 6 km of the route – most could walk or cycle from home within 15 minutes;

- 60 primary schools with 16,922 pupils lie within 2km and 82 primary schools with 24,012 within 6km;

- 34 secondary schools with a total of 16,072 pupils lie within 2 km of the Lee to Sea route, and further 3 schools (Scoil Mhuire, St Aidan’s Community College and Douglas Community School) with a further 1,711 pupils lie within 6 km of the route;

- The route directly connects 37 of Cork County’s 85 secondary schools, with one another, and with the city and sea;

- 19 hotels offering 2,212 rooms lie within 2km of the route.

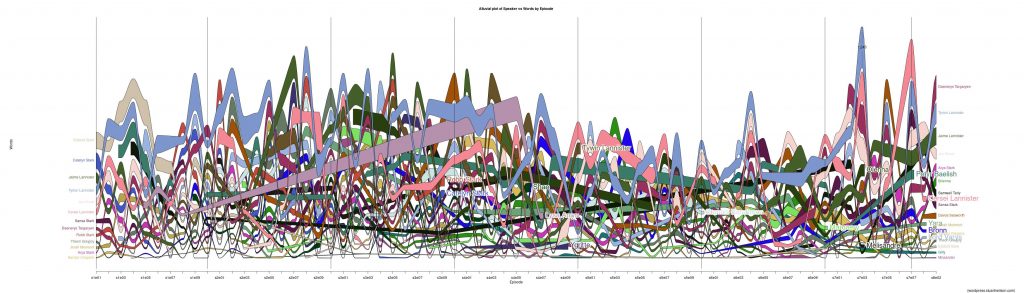

| Within 2km | Within 6km | In Cork City + County | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | 157,356 | 228,731 | 417,211 |

| At Work | 65,439 | 97,103 | 179,890 |

| Primary schools | 60 | 82 | 342 |

| Primary pupils | 16,922 | 24,012 | 63,574 |

| Secondary schools | 34 | 37 | 84 |

| Secondary pupils | 16,072 | 17,783 | 42,893 |

| Hotels | 19 | 23 | 49 |

| Hotel rooms | 2,212 | 2,538 | >3,943 |

All analysis was performed with open source software using publicly available data, and all software and data sources are provided in the links at the end – also annotated R code used to generate these outputs. The technical description may be a helpful tutorial in using public data and mapping sources. This analysis was proposed by Orla Burke and Pedestrian Cork.

Continue reading 15 minutes from the Lee-to-Sea Greenway