Creating Autism – a four-part posting

1 History – 2 Geography – 3 Perspective – 4 Conclusions

Autism: Nature, Perception, Word

Autism is a collection of natural phenomena, a syndrome of traits and behaviours that arise from neurological variations in early development. A combination of sufficiently clear autistic signs, in a particular set of combination, will be perceived by a trained observer as ‘autism’ and then assigned a particular diagnostic label for future intervention.

Autism is a set of perceptions and portrayals of autism, as specific characters in fiction, as stereotypes of what autistic people are like, and as psychiatric and educational expectations of how this diagnosis is managed.

Autism is a word, a symbolic shorthand used to simplify communication about a complex world of perceptions and phenomena into clear and concise language. ‘Autism’ is a special educational need and a residential care plan.

Autism exists simultaneously in multiple, overlapping plains – natural phenomena, perceptions, and words – that serve to both highlight and to obscure the people who inhabit the label. Being autistic means having some elements of the diagnostic criteria that make up autism, but in a unique and individual combination. Being labelled ‘autistic’ is a key to intervention and understanding, but the label also obscures the human complexity of the person who has been labelled. No two autistic people are alike.

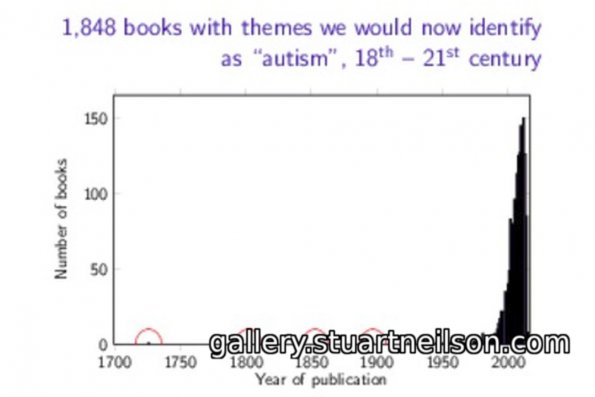

Autism has changed dramatically since it was first used in its modern sense, and the label continues to evolve with scientific enquiry and professional experience. As a result, when two different people say ‘autism’ they are probably saying two different things. The autism of 2019 is not the same set of phenomena or perceptions as the autism of 1952. The autism portrayed by the character Raymond Babbitt (Dustin Hoffman) in ‘Rain Man’ in 1988 is not the same as the autism portrayed by Billy Cranston (RJ Cyler) in ‘Power Rangers’ in 2017.

Autism, being bound to perceptions, portrayals, individuals and events, means different things in different places. The presence of genetic research, community support, special educational resources, personal tragedy or charismatic autistic speakers all colour the reporting and representation of autism at specific times and in specific places. Self-image and self-worth are also coloured by public representations of others who share the same label. The attitudes toward people labelled with autism are shaped by public representation.

Choosing how to talk about autistic people – and the words are most definitely a choice – has a profound impact on how interventions for autism operate and how autistic are perceived and integrated within society.

(Re)Creating Autism: Autism Narrative

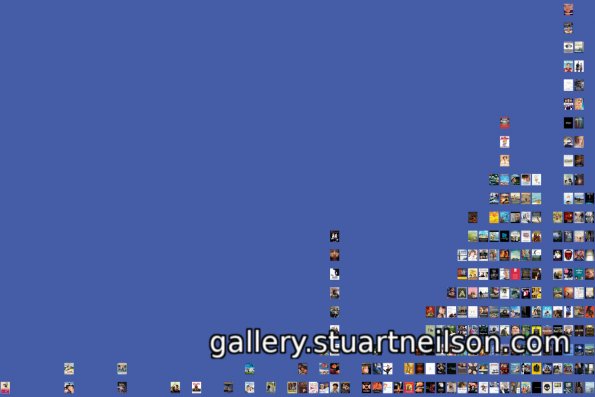

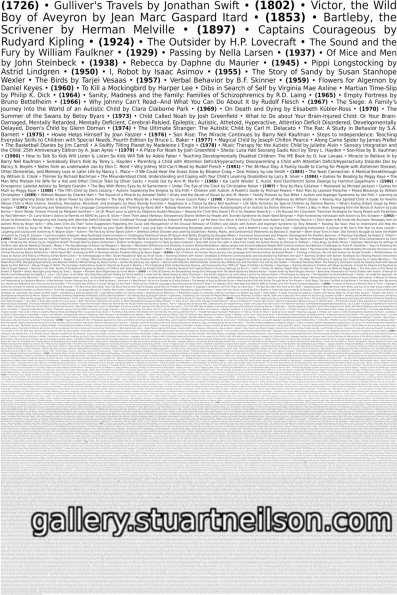

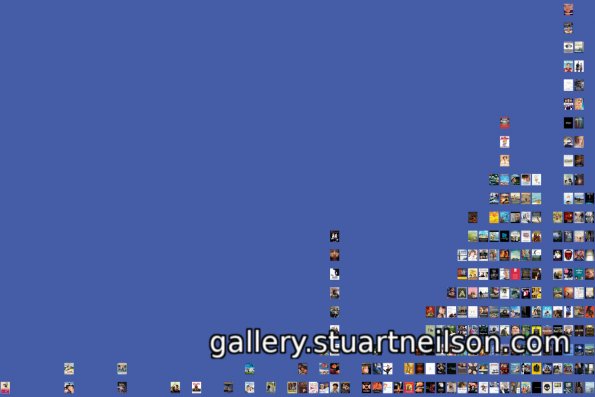

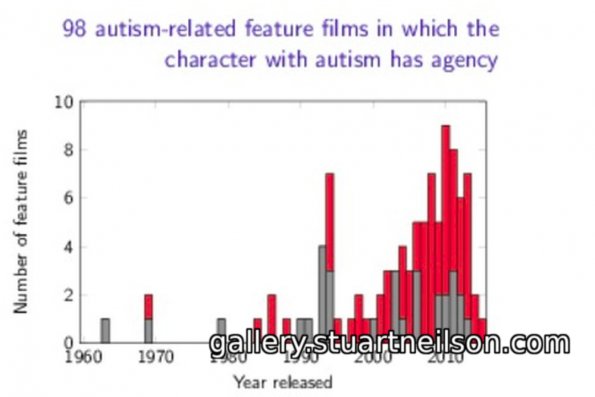

The number of books published ‘about autism’ or including more-or-less ‘autistic’ characters has risen from 1 or 2 titles per century to tens or even hundreds of titles per year now. Twenty or more mainstream films with an autism theme are released every year. Autism fiction has surpassed text books and non-fiction as the overwhelming source shaping autistic identity.

The pre-eminent publisher of autism and Asperger syndrome related books is Jessica Kingsley Publishers, with 847 titles in their current book catalogue.

The Goodreads book review website lists about 6,207 autism-related fiction and non-fiction books, currently adding more than 150 newly published titles every year.

The vast majority of ‘autism’ in fiction is written by, and intended to entertain, a mainstream majority of non-autistic viewers and readers. Autism and autistic characters in fiction are most often metaphors of hardship, social exclusion, global change and other mainstream themes. Fiction rarely depicts the experience of real autistic lives.

Fiction succeeds or fails on the degree to which we, the audience, affirm or reject themes and depictions. Fiction is also a product of imagination and experience — in this case, experience with real autistic lives. Autistic writers, actors and documentarians are gradually being recognized, bringing their own perceptions and priorities with them.

We can reclaim the metaphors, affirm and reject depiction, and offer up our own experiences for imaginative writing that creates a better autistic future.

Stuart Neilson

I received a diagnosis of Asperger syndrome in 2009, at the age of 45, which was the culmination of several years of unpleasant and ineffective in- and out-patient psychiatric treatment. The diagnosis, for me, was a lightbulb moment that made sense of my feelings of anxiety in public spaces and in social settings, as well as explaining my lifelong feelings of isolation and exclusion.

_595_stuartneilson.jpg)

_595_stuartneilson.jpg)

Asperger syndrome is a part of the broader autistic spectrum. From my own experiences, I feel that autism maintains a strong connection with sensory experiences, at the expense of language. I can be easily distracted, or I can be intensely preoccupied by my senses. I notice changes that many people do not notice, but find it hard to cope with unexpected change. Busy places with lots of lights and noise can be very hard, and make communication very hard work. These pictures try to capture my sense of place and movement.

The word pictures use articles about autism from the Irish Examiner, Irish Times and Irish Independent over the past fifteen years and text from medical textbooks to examine how people talk about autism. Written portrayals not only describe autism, but also shape how autistic people are perceived and treated. Careful use of language helps to shape a more inclusive, respectful and tolerant attitude to difference.

_595_stuartneilson.jpg)

I lecture and write about the autism spectrum, both as a health statistician and from my personal perspective. I was a founder member of the team that developed the innovative Diploma in Autism Studies at University College Cork, Ireland. I have a degree in computer science and a doctorate in mathematical modelling of inherent susceptibility to fatal disease.

My most recent publications include ‘Living with Asperger syndrome and Autism in Ireland’, ‘Painted Lorries of Pakistan’ and a chapter on sensory issues and social inclusion in the anthology ‘Knowing Why: Adult-Diagnosed Autistic People on Life and Autism’.

You can read more about some of these ideas at my website, wordpress.stuartneilson.com and about the exhibits in “Creating Autism” at stuartneilson.com/creatingautism/.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to so many people who have supported and encouraged me in producing the material displayed here, and for valuable criticism in paring everything down to the final display. Firstly, my family and especially Chryssa Dislis who has been a constant eye for detail and structure. Secondly to Danielle Sheehy who has seen this material through from a pile of unsorted, scruffy printouts to the panels on the walls – and especially for seeing the potential to exhibit this as anything other than academic writing.

The wonderful group of people who agreed to present talks did so without hesitation and are amazing for having faith in the outcome. Thank you Megan Goodale, Gillian Harold, Katerina Karanika and Danielle Sheehy for your enthusiasm.

Finally, I would never have managed to achieve any of this without the support of Aspect, the Adult Asperger Syndrome Out-Reach Service of the Cork Association for Autism, who have supported me for the past decade. My key worker Yvonne Scriven has always promoted a sense of autonomy and self-advocacy, andcounsellor Tom Ryan has always been prepared to listen to and engage with ideas and discussion.