The Rosie Result is the final installment of Graeme Simsion’s brilliant, funny and true-to-life observations on the life and love of the quirky, possibly autistic Professor Don Tillman.

Don Tillman is now back in Australia, as quirky as ever and as prone to inadvertent trouble as ever, except he has an 11-year-old son following in his footsteps and at the terrifying threshold before the transition from primary to secondary school. Both Don and Hudson find themselves in different kinds of deep mess, not entirely of their own making. Both cope in their own ways, prioritizing and sorting through with determination.

School

I loved The Rosie Project, which had some acute observation of people like me – people who function well in a whole range of domains, but suddenly come upon the most disabling barriers because of unknown social expectations or an inability to manage the simplest of coordination, memory or sequencing tasks. Don Tillman is clearly a composite based on observations of real people, working (and occasionally spectacularly failing) in a domain like mine.

Now, with Hudson on the threshold of secondary school, Don reflects on a lot of his own parenting and schooling, interwoven with current events in Hudson’s life. Can an autistic person be a good parent? Of course. Does he get it right? No, but which parent does? I certainly didn’t, and continue to try, with (hopefully) happy, well-adjusted offspring.

I desperately tried to avoid repeats of my childhood, which was one of bullying, homophobic taunts and violence, from pupils and staff. My behaviour – pre-Asperger syndrome – was cheeky, obstinate, anti-authoritarian and full of “personality clashes”. I attended 11 different schools (all mainstream, with one brief spell in remedial education) and was moved because I was bullied in addition to being a problem pupil. Alternating between 100% in subjects (or at times) when I just got it, and 0% when I didn’t, was always seen as a deliberate act of rebellion, not a frustration for me as much as the teacher.

As you might guess, I don’t readily believe in “challenging behaviour”. I do believe in “challenged teachers” – one who smacked with the flat of ruler the first time, with the edge the second, and across the knuckles of the dominant hand on the third was a challenged teacher.

There is a lot of real pain behind the episodes, and Graeme Simsion brings out a rich experience of school as I experienced it. One event is uncannily similar to the time my chief tormentor was elevated to prefect – a position that permits teacher-approved bullying – so I researched his favourite sweets, bought him a half pound and presented them in school assembly with the loud message “Thank you for being my friend”. Nobody wants to be seen in the same place as the class queer after that. And, in my case at least, it was a premeditated act to employ homophobia to my benefit for a change (and yes, I should feel shame).

Our own ‘Hudson’

We have two children, who followed two childhood trajectories. From very early on I could see one of them reacted as I did, played as I did and (even at 4) got in trouble at school as I did.

We ignored it at first, thought seriously about the “doen’t contribute in class”, “can’t work in a group” and “doesn’t play nicely in breaktime” comments, and did our best to address them. Unlike most parents, we have access to my professional contacts, my own psychiatrist, occupational therapist and above all my support through the only publicly-funded adult autism support service in Ireland. The first school had a poor response to special needs and resource provision, extracting children from other activities and from social opportunity in order to engage with special needs inside the stationary cupboard. There was more than a strong hint of “will never be able to …” and “might be better served elsewhere”. So we made spreadsheets of the costs and benefits of an assessment – how much limitation and stigma went with being labelled autistic in that school, versus how much resource and additional supports we might gain.

The transition to secondary school went smoothly enough, and the battles with school teachers demonstrated an incredible resilience and personal self-worth that I lacked at the same age. Eventually there was too much similarity to my clumsy use of one hand (or the other, I’m not choosy) to eat because two pieces of cutlery is impossible, the inability to follow a list of more than 2 items, the rigid rule-following, the catastrophizing when events differed from plans or expectations (which is even harder on holiday, overseas, in a strange language when austerity closes the ATM machines) and the frustration of inexpressible emotions. An OT said no child would copy a parent so obsessively, no matter how attached, when doing things the easy way is so much less work. So we went ahead, knowing that – in Ireland – assessment must be completed by age 18 or there is no DARE, no IDEA, no other adult supports at all without a diagnosis before leaving school.

There have been two challenged teachers in particular for whom having a medical diagnosis allowed them to move beyond thinking of our child as bad or lazy and seeing potential where they had not before the diagnosis. I wish teachers did not require children to be assessed by a battery of psychological, occupational therapeutic and psychiatric test just to treat them as individuals, but I am glad it has been a positive step for us.

(Catastrophizing is to make a mountain out of what seems, to others, to be a molehill. Graeme Simsion includes a beautiful vignette of Hudson swapping before- and after-meal time because the meal is served later, but pre-meal time is homework time, not reading time, so he can’t read and “my whole week is messed up. This is totally wrong.” Imagine being in our home with two catastrophizers who back each other up about trivializing our mountains, or in a car that takes a wrong turning, or when guests are inexplicably late – or early.)

Most of all, I don’t want my child, or anyone, to experience the avoidable mental health difficulties I have had. Knowing who you are and why you feel, and are perceived by others as, “different” or “odd” is a big step towards not being hurt, excluded and alone because of those feelings and perceptions.

Diagnosis or identity

The book’s characters struggle with the idea of Asperger syndrome, or autism, or Aspiedom, or whatever you wish to call yourself as an identity, as opposed to a diagnosis. The book does not struggle, it conveys the confusion around stigma, resourcing and self-awareness very well.

Personally, autism only makes sense to me within the context of disability. Society places barriers in the way of people who are different. Disablement – the process of being disabled – is separate from autism. Not being able to mentally juggle a list of more than three items becomes disabling when shopping on Amazon, where you can’t see your list and continue shopping. Not being able to navigate a shopping centre through noise, or pick out actual road signs from advertising, or say the appropriate words in the right order expected by a shopkeeper, are all disabling. I leave the shop about one third of the time I go shopping, because the products have moved, or the person behind the till looks angry to me, or the noise is excruciating. That is a disability.

But equally, there are so many positive life lessons to share – the comfort objects that people keep in their pockets, the tips of which quiet places are out of the rain and open on a Sunday, how to get into a shop by a side entrance that few people notice, or little rules that make social transactions into a knowable code. That becomes an identity.

Hudson is clearly disabled by the requirement to contribute in class, make friends, play sport or do mathematics in the way expected of him by his teachers. Hudson’s teachers and Hudson’s school are challenged. Hudson does not “have a disability”, he is actively disabled by the choices that school makes in educating and assessing people according to an unnecessary set of expectations. Hudson can achieve the required outcomes, if only the processes and expectations reasonably accommodate all children.

Life lessons

Another episode in Don’s life reminds me so much of the effort to fit in, to be “one of the boys” and do do what “normal” people do – the dress codes that any sensible person would look back at and laugh (you’ve seen 70s and 80s fashion and hair). And all of it so transient, unnecessary and irrelevant. Yet so many children, right now, are desperately unhappy trying to fit in, to make friends and to be friends.

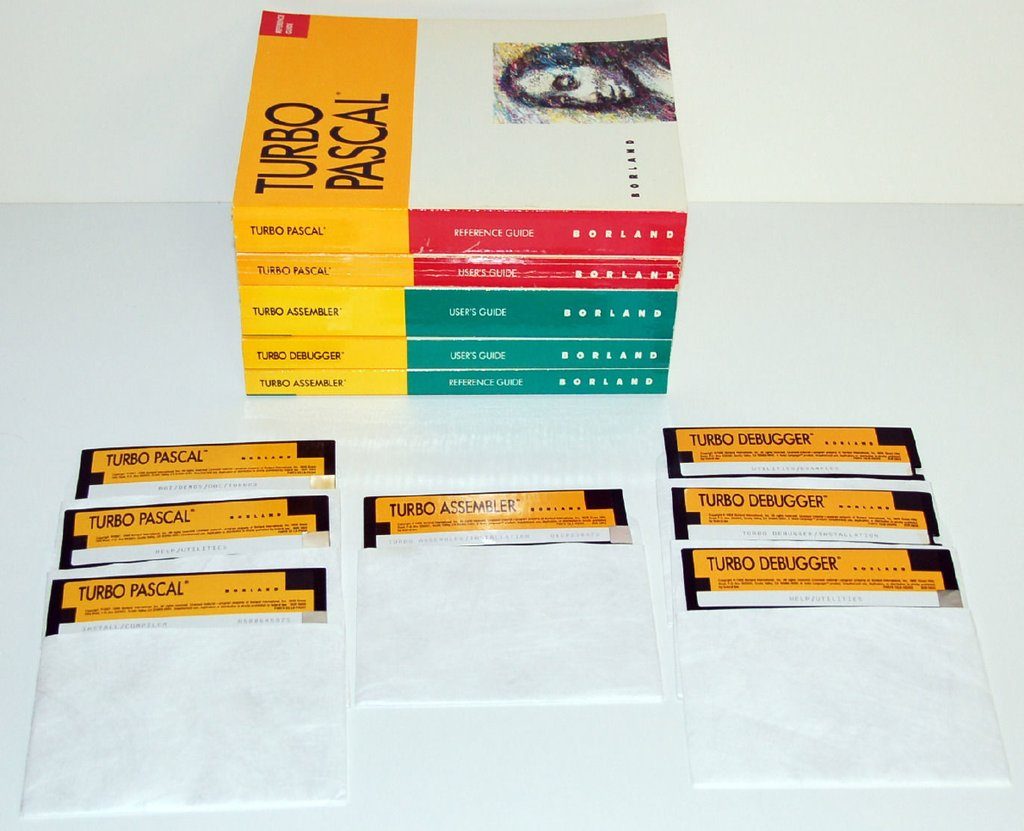

There is no magic in friends, or in romance. Relationships take care and commitment, and they are hard work. I remember the lace episode in my own life, an anniversary gift that went straight back to the shop to be exchanged. My wife, bless her, took me in as a useful lesson in things that actually matter. Before the lace episode was the Borland Turbo Pascal episode – in which, of course, I would have been thrilled to receive a computer language compiler at least as good as the one at work, so it would have to make an excellent anniversary gift:

That one didn’t fly as well as the lacy underwear.

You can’t buy friends, or bribe them, or convince them to like you by force of argument. It takes effort from both sides, but more (I suspect) from me than most others. There are people who accept you for who you are, and the strange, quirky and occasionally misguided attempts to display affection.

Some people have noticed and commented on my NC lapel pin (Vibes & Scribes for beads, plus a Greek eye). The label was written on my medical notes by an angry, challenged psychiatrist, after which I was treated like dirt for 4 years until my wife challenged a throwaway comment about me being a “non-compliant, non-attender”. She, strangely enough, is not labelled with “challenging behaviour”, even though she is incredibly militant and effective. The eye is a common theme in Greece and the Middle East, a magical symbol that has power to both attract and to ward off evil. Superstition seems an appropriate counterpoint to the misguided scientific / medical label.

Concluding remark

If you went through school as an undiagnosed autistic pupil, or suffered the wrath of adults who found it easier to call non-compliance a problem behaviour, or are trying to work through the same problems with your own kids now, you will find this a timely novel.

But above all, it is funny.

The Rosie Result is not released until April here, but you can buy a paperback right now from Text Publishing or instantly download a Kindle copy from Amazon.co.uk .

What a remarkable expose of both the Rosie project trilogy underlay and your own experiences. Thank you for helping me understand autism as a disability a bit better. My DIL will thank you for that.