I have talked and written about ‘social calories’ to describe the impact that social interaction has on me, usually in terms of trying to limit my intake of social calories. This would often mean a choice between one activity with lots of gentle socialising or another with shorter, intense interaction. Too many social calories make me (physically) sick if I don’t pace myself. In short, Daisy wrote of one social occasion, “a surfeit of ‘social calories’ – the effort of making social contact with so many unfamiliar people in such a short time, and eating unfamiliar food, made me feel sick.” The Enchanted Doors, “A Book to Read When You Have Asperger Syndrome”. You can watch a presentation with visuals — about 13 minutes in, I talk about social calories and social misunderstandings in The Spooky Powers of Normal People).

A wonderful post by Sonia Boué on ‘social libido’ brought social calories to mind, and how social contact might be managed with this concept — I assume it is better to remain in the world, rather than become socially-avoidant and exclude myself from it. Sonia Boué writes about an intense day travelling and taking part in a three-hour refugee solidity march, with 90,000+ other people and their high emotions, and how this experience affects people across the neurodiverse spectrum to different degrees.

Rather than accepting the limitation and pacing myself to match the limitations, the concept of ‘social libido’ implies mechanisms that could modify social-seeking, social reward and tolerance of social calories. Sometimes (e.g. the modern-day airport experience) complete strangers will insist on intimate intrusions, and sometimes (e.g. a job interview) the rewards of putting yourself out there are too great to miss.

Autism and the social instinct

In Kanner’s worldview, autism is defined by an inability to relate to the self and to others, an autistic aloneness where self-isolation is the preferred state. By contrast, Asperger identified a social awkwardness that could be nurtured into social inclusion. Lorna Wing defined the autistic triad as deriving from “an absence or impairment of the social instinct”, from which arise the three impairments of social interaction, social communication and social imagination. Asperger and Wing did not believe that autistic people have no interest in social interaction, but that they have a difficulty in finding social engagement that is positive.

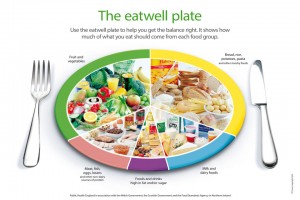

In my opinion, everyone craves human contact and people who lack human contact feel that lack. Children with autism are far more likely to hover at the boundaries of social engagement, and often make ‘socially inappropriate’ overtures. The experience of rejection drives people further and further from the boundaries with age, and many adults with autism are more reclusive than they were in childhood. They tried to be social, in their own ways, and were not understood. Just as everyone needs sufficient food for sustenance, and food that is in balance, so everyone needs positive human contact. The Eatwell Plate recommends one-third of diet from fruit & vegetables, one-third from starchy foods and the remaining third from dairy, proteins and ‘treat’ foods. This is a guideline, and should be varied to match personal build, physical exercise and general health — we are not all the same. Some people crave more and crave greater intensity, some are satisfied with simplicity and moderation.

In my opinion, everyone craves human contact and people who lack human contact feel that lack. Children with autism are far more likely to hover at the boundaries of social engagement, and often make ‘socially inappropriate’ overtures. The experience of rejection drives people further and further from the boundaries with age, and many adults with autism are more reclusive than they were in childhood. They tried to be social, in their own ways, and were not understood. Just as everyone needs sufficient food for sustenance, and food that is in balance, so everyone needs positive human contact. The Eatwell Plate recommends one-third of diet from fruit & vegetables, one-third from starchy foods and the remaining third from dairy, proteins and ‘treat’ foods. This is a guideline, and should be varied to match personal build, physical exercise and general health — we are not all the same. Some people crave more and crave greater intensity, some are satisfied with simplicity and moderation.

Sonia Boué’s ‘social libido’ post arose from a brief exposure to intense contact with others, in a way that many people seem to find not merely “enabling, fruitful and highly enjoyable”, but essential to their well-being. Aspects of the excursion, the people and the solidarity march raise interesting questions about how to modify social libido — are there settings, structures and attitudes that increase the ‘social instinct’ or improve the autistic response to social interaction? Greater acceptance from other people and common purpose help turn attention away from difference and ‘inappropriateness’. Neurological diversity does not stand out against the incredible cross-section of society at the refugee solidarity marches (much as some people describe their autism disappearing in a foreign country, where all foreigners — including their discomforted parents — are ‘other’). The protest banner acts as a totem to focus the attention of everyone, away from the individual and towards the common purpose.

Social calories — in the food and in the context

The idea for social calories came to me after I was diagnosed with Asperger syndrome. I have always had difficulty eating some foods — ‘a sensitive gut’ (if I’m lucky) or ‘a picky eater’ — but had little success in narrowing down the cause of the food intolerance. Some foods almost invariably caused problems, but not in a way that made biological sense. I have a diagnosis of IBS, which essentially confirms that I have a sensitive gut, without identifying practical steps to resolve the symptoms.

One of the foods which invariably made me physically ill is the Greek and Middle-Eastern pastry baklava (left, in the photographs), sheets of filo pastry stuffed with nuts and honey, cut into appetizing diamonds. The flavour is divine, the consequences are not. An enduring mystery for me was that I love another sweet called kadaïfi, made from (strangely) filo pastry, stuffed with nuts and dripping in honey syrup. I have never had difficulty eating the second sweet, despite their similarity. The ingredients for these two pastries varies, but usually goes something like this:

One of the foods which invariably made me physically ill is the Greek and Middle-Eastern pastry baklava (left, in the photographs), sheets of filo pastry stuffed with nuts and honey, cut into appetizing diamonds. The flavour is divine, the consequences are not. An enduring mystery for me was that I love another sweet called kadaïfi, made from (strangely) filo pastry, stuffed with nuts and dripping in honey syrup. I have never had difficulty eating the second sweet, despite their similarity. The ingredients for these two pastries varies, but usually goes something like this:

Baklava

- filo pastry

- chopped walnuts, almonds, pistachios

- unsalted butter

- ground cinnamon, clove, cardamom

for the syrup:

- sugar

- honey

- water

- lemon juice

- cinnamon

Kadaïfi

- kataifi pastry

- chopped walnuts, almonds, pistachios

- unsalted butter

- ground cinammon, clove, cardamom

for the syrup:

- sugar

- honey

- water

- lemon juice

- cinnamon

Within weeks of diagnosis, I went to the fabulous Mr Bell’s in the English Market and ordered some fresh baklava from a well-known Greek patisserie (no room for unknown variables here) and ate them, in comfort, at home, with an enjoyable film. And waited. There was no unpleasant outcome at all, so the mystery ingredient is not in the cake, but in the aura around it.

Modifying social libido

If the basic intolerance is a limited capacity for social interaction, there must be ways to burn off the calories without being ill, to exercise for greater capacity and to choose the composition of social interaction. Perhaps there is even an autism-friendly condiment, like guessing the purpose or origin of an unusual object placed in the middle of the dining table, or socialising around a common purpose.

At the same time, there is not a ‘healthy amount’ of social interaction that everyone must be forced to achieve (although psychologists and psychiatrists sometimes do insist on meeting a quota). One definition of sexual health is “having the sex that you want — including none — in a safe way, without risk of harming yourself or others physically or emotionally”. Health is not defined by quantity or intensity, but by quality and meeting the individual libido.

Book extract

Book extract

On a purely practical note, “Living with Asperger Syndrome and Autism in Ireland” has a chapter on sensory experiences, and learning to live with sensitivity. The following paragraphs are very relevant to the sensory aspects of the places that we socialise:

Learning to handle unpleasant sensory experiences, whether noise, smell or any other, comes down to managing exposure, increasing personal tolerance of the experiences and having coping strategies for your own aversive reactions. The first issue — managing exposure — is something that you will never have complete personal control over, unless you wish to become a hermit. Some exposure is open to compromise with people you live, study or work with — for instance it may be reasonable to expect not to have to listen to loud music or power-tools at times when you should be studying or working. It should also be reasonable to ask that people do not eat food with strong smells (or that involve a lot of mouth noises, like crisps or bubble-gum) in a shared work space — and that they dispose of food waste in an appropriate place, like the kitchen or outside bins, rather than an office or bedroom waste paper basket.

However, not all unpleasant sensory exposure is ever going to be within your control if you wish to live a fulfilled and involved life. Some people will not understand your sensory issues, others will trivialise them and on many occasions the noise, flickering light and smell are an unavoidable consequence of everyday activities that people take for granted. Keeping sight of the benefits can often make the unpleasant much more bearable. Going to work, earning an income and having a relationship with colleagues is a huge incentive to put up with the sensory issues that almost any workplace involves.

An important part of managing exposure, when exposure can be moderated, is the ability to predict both what your own issues are and the activities that are your personal triggers. You might not even be aware of the precise sensory issues that you have because sensory exposure so often occurs as a collection of related experiences. Finger-food or buffets are often a feature of stand-up social occasions with a lot of strangers, brief conversations and dressing for show, including wearing perfume and after-shave. A roomful of these different exposures from so many people can leave you dazed and nauseous, without knowing which elements of the social occasion make you feel unwell and you might blame everything from the jumbled conversation to the rich food. I blamed my own food intolerance and nausea on buffet food for years until I realised that I was suffering from an excess of ‘social calories’, the sheer emotional effort of making and breaking social contact with so many people in a short space of time. The food itself, as I know now, is perfectly edible to me, as long as I limit the event to just showing my face and leaving as soon as it is polite to do so. An occupational therapist can be an excellent source of help in pinpointing your own specific sensory issues and separating the issues that cause the most personal distress from other sensory exposures that you usually feel with them.

Some methods of building tolerance include progressive exposure, a ‘sensory diet’ (often supervised by an occupational therapist) and sound therapy (auditory integration training). These methods have mixed results, and while some people report great success, others report no benefit whatsoever. We are not aware of any reports of having worse sensory issues after therapy, so they do not do any harm — except, of course, that private therapy can be very expensive and can run for many sessions.

Methods of improving your coping skills when you do experience unpleasant sensory situations include meditation or yoga, progressive muscular relaxation (PMR), mindfulness therapy and controlled breathing. All of these can be used ‘in the moment’ to cope with anxiety or rising panic that occurs during a stressful sensory experience, but all are very much more effective if they are practised regularly, preferably at times of peace and calm in a safe environment. The recall of the safe, peaceful environment helps during exposure to anxiety and chaos elsewhere. Meditation or yoga are taught in many health centres, in some schools and through GP or HSE services. There are many books on using yoga to achieve personal calm, and although some yoga books are associated with religious beliefs, it is unlikely to conflict with most people’s religious (or even atheist) beliefs. Progressive muscular relaxation is a method of progressively tensing and then relaxing each set of muscles in your body, from toes to face, in time with slow breathing and thinking about a pleasant and safe place. Progressive muscular relaxation is an effective way of reaching a state of calm while retaining a sense of personal control, which can be recalled during times of stress. Progressive muscular relaxation is used within anxiety management courses and other therapies in the HSE and other health centres — there are very many CDs available in bookshops containing spoken instructions and mood music to listen to and practice PMR in your own bedroom or other safe place. Mindfulness is another form of meditative therapy that has come to the fore in recent years as an effective method of getting in touch with bodily sensations and emotional feelings, often using quiet and slow breathing to become aware of the immediate surroundings and then aware of the sensations within your body. Mindfulness is one of the most frequent techniques used within psychological therapy practised by the HSE, and there are many books in general bookshops explaining the techniques used. The last technique, and the most immediate, is something that can be practised in moments of stress as well as during calm — breathe in while slowly counting to, perhaps 5, and then out while slowly counting to 5. Repeat the cycle of in and out for ten breaths. The more often that you use a technique like this (there are many variants), the more effective the results will be.

Most of us are too old or too self-conscious to get away with carrying a Linus blanket or comforter, but there are plenty of adult alternatives that can provide a familiar, predictable sensory comforter. This might be an article of clothing like a scarf, but key-fobs or strings of beads (like a rosary) are very good sensory comforters that you can hold in your hand, in or out of your pocket, without attracting any attention — counting through beads, especially sets that have marker beads, can be combined with slow breathing.

3 thoughts on “Social calories and autism”

Comments are closed.