Hans Asperger published his first paper on autism in 1938 in German in the journal Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift [The Vienna Clinical Weekly], five years before Leo Kanner’s first publication in 1943 in English. These were by no means the first papers about “autism“, because the term was already used in the description of schizophrenia by Eugen Bleuler in German in 1913. Four strands of work – about autism and schizophrenia, in German and English – continued to both enhance and confuse the understanding of autism for decades. Most notably Asperger’s 1938 contribution was ignored as the pre-war prominence of Viennese medicine gave way to post-war shame and disgrace.

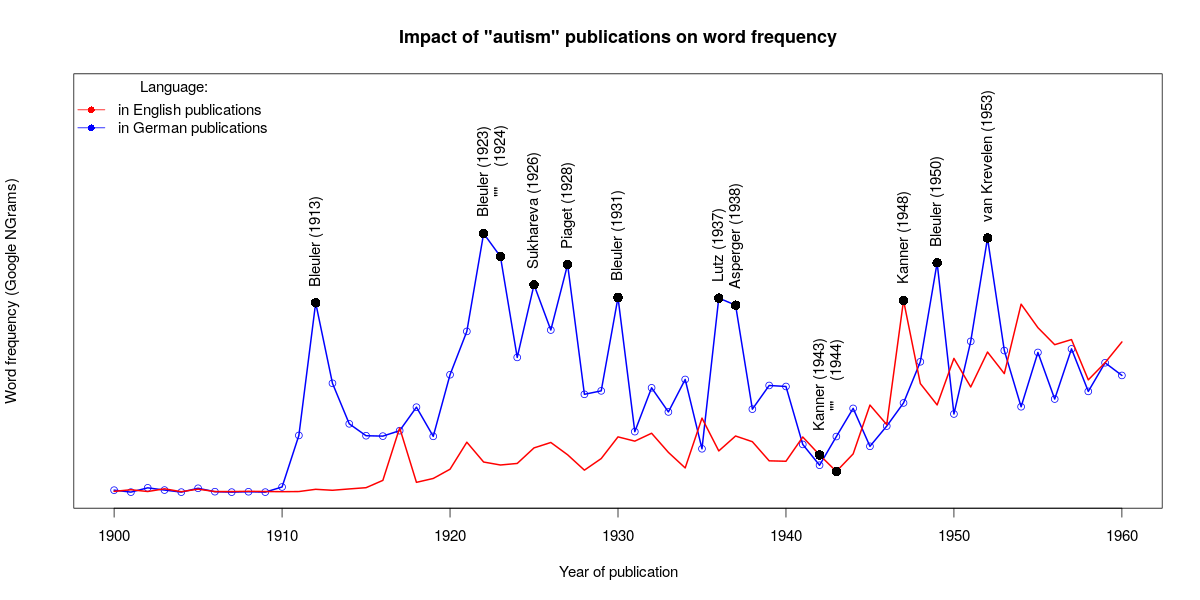

The transformation of “autism” from a predominantly German term in schizophrenia, to the predominantly English term we undersatnd is summarised well in the word-frequency plot of the publication sequence.

This plot displays the frequency of the words “autism” and “autistic“, and their German analogues “autismus” and “autistische(n)” in a large number of printed works analysed by Google NGrams. (These works are papers, magazines, books and library holdings scanned by Google – they include both general and scientific texts). The frequency in German rises suddenly in 1913, peaking throughout the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. In the post-war decades the English word frequency equals and occasionally exceeds the German word frequency, until firmly overtaking German from the 1950s onwards.

Autism words in English are currently about 8.5 times more frequent than autism words in German, reflecting the wider range of scientific publications, films and newspaper reports about autism in the English language. The earlier period is interesting and had a great impact on the understanding of autism and treatment of autistic people for many decades.

The beginning

The Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler published one of the most complete descriptions of schizophrenia and schizophrenic thought processes in German in 1912. Bleuler’s conceptualisation described the loosening or disturbance of four core thought processes, “The Four As“, and the splitting (schism) between them:

- affect – expression of emotions appropriate to context

- autism – social withdrawal

- ambivalence – simultaneously holding conflicting attitudes and emotions

- associations – thought associations and order

The term “autistic thinking” as defined by Bleuler is an aspect of healthy functioning, one four that are loosened or disturbed in schizophrenia. Bleuler’s autistic thinking is “detaching oneself from outer reality along with a relative or absolute predominance of inner life”. In excess, you would lose your connection to environment and other people, and the distinction between dreams and external things.

Autistic thinking can be healthy, in balance with the other three core thought processes. Without autistic thinking we would have no art, philosophy, fantasy, daydreams, the drive for knowledge, the quest for human origins, religion, prayer, superstition and magic ritual.

Bleuler published a well-received Textbook of Psychiatry in German in 1923, translated into English in 1924, which cemented the terms and concepts of his description of schizophrenia.

Bleuler was widely referenced in later prominent publications, including a book by the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget in 1928 and his own English language work on schizophrenia in 1950.

The origins of the “autism” we know

A number of different authors – in Austria, Russia, Switzerland and the United States, writing in German and English – have described cases of “childhood schizophrenia” and “infantile autism” leading up to the definitions we have now.

Their prominence does not match the chronological order of publication (which you can trace through German and English in the graph above), in part due to the language difference and (post-war) to the opprobrium of German psychiatry and medicine.

Grunya Ssucharewa (as spelt in her German publication of 1926) was a Russian child psychiatrist who described children who were probably autistic, as we now understand the term. Her name (Груня Сухарева) is also spelled Suchareva or Sukhareva.

Jakob Lutz was a Swiss child psychiatrist who published a description of cases and an overview of childhood schizophrenia in German in 1937.

Hans Asperger published the first description of children firmly within the modern autism spectrum, including many of the features essential to current descriptions. This was published in Austria, in German in 1938, shortly after the Nazi annexation (anschluss) of Austria. This paper has not been published in English and is widely cited incorrectly (for instance it is volume 49, not 51 as most commonly stated).

The French-born US psychologist J. Louise Despert published a description of schizophrenia in children in English in the same year, 1938.

Kanner and autism

Leo Kanner was Austrian-born and working in English in the US when he published the seminal work on “autistic disturbances of affective contact” in 1943, followed by “early infantile autism” in 1944. These works clearly delineate a different group of people than those encompassed by schizophrenia, with an exclusively early onset.

Asperger’s most widely quoted work on “autistic psychopathy in childhood” was published in 1944, translated into English by Uta Frith in a chapter in her book on autism and Asperger syndrome in 1991. This brought out the wider spectrum of autism and established the diagnosis of Asperger syndrome as a distinct entity within the spectrum.

It is really important to note that the word “psychopathy” used by Asperger means disorder (-pathy) of the mind (psyche), as opposed to a physical or organic disorder of the body (soma). The word also has nothing to do with the crime-writers’ favourite word “psychopath” (more correctly “sociopath” or antisocial personality disorder). Asperger’s “psychopathy” would be rendered in English as a “mental“, “psychiatric“, “psychological” or “personality” disorder and “autistic psychopathy” as “autistic personality disorder” or simply “autism“.

Separating the strands

Kanner’s 1948 textbook of child psychiatry in English in 1948 was quickly followed by Bleuler’s 1950 English book of his schizophrenia conceptualization. Bleuler took the opportunity to criticize the misuse of “autistic thinking” within medicine and carefully define his terms. Works by the Dutch child psychiatrist D. Arn van Krevelen were also significant in 1952, describing Kanner’s description of autism as quite distinct from Asperger’s description of “autistic psychopathy“.

By this point in the history of autism it should have been clear that autism is lifelong, does not develop in adolescence or early adulthood (although it may be recognized late) and does not progress or remit and relapse. Other differences should have been clear in distinguishing between autism and schizophrenia on assessment, but unfortunately the early intertwining of autism and schizophrenia has had a lasting impact on the understanding of autism and autistic people. There are, of course, common features in both conditions and it seems highly probable that some genes are related to function in both conditions. But autism is not “childhood schizophrenia“.

Impact in medical literature

The recognition accorded to each author and title can be assesed by the number of times the work has been cited – primary works, important authors and influential ideas are more frequently cited. This is an alternative to the response in word frequency summarised in the graph above, and reflects a notional sense of scientific worth.

Google Scholar is a public searchable database of scientific papers that includes a rough-and-ready citation count. There are paid services that provide much more comprehensive and accurate citation and impact measures, but Google is good enough for these purposes.

The number of times each of the 16 papers outlined in the text is plotted in the chart above. These are the same 16 papers as graphed in chronological order in the word frequency diagram earlier. Kanner (1943) is far ahead with nearly 10,000 citations, followed by Bleuler (1950 – the English text) with nearly 6,500 citations. Asperger (1944) lags far behind at just under 2,500 and Asperger (1938 – the untranslated German paper) at just 66 citations.

Context

The context of this sequence of papers in their languages, geography, disciplinary boundaries and professional relationships have had a profound impact of the respective recognition of the concepts they contain. This has impacted the definition of autism, the speed of adoption of useful concepts and the important distinction between different conditions – and the appropriate responses to them.

It has also, of course, impacted the public and professional understanding of autism and autistic people. The current concept of “autism” remains fluid and it is critical that the term and its boundaries encompass people in ways that relate directly to appropriate supports.

Papers mentioned

- Bleuler, Eugen (1912) Das autistische Denken. In Jahrbuch für psychoanalytische und psychopathologische Forschungen (Leipzig and Vienna: Deuticke), Vol. 4: 1-39.

- Bleuler, Eugen (1923) Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie. Berlin: Julius Springer.

- Bleuler, Eugen (1924) Textbook of psychiatry. New York: Macmillan.

- Ssucharewa, Grunya (1926) Die Schizoiden Psychopathien im kindesalter. Monatschrift fuer Psychiatrie und Neurologie, 60:235-261.

- Piaget, Jean (1928) Judgment and reasoning in the child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Bleuler, Manfred (1931) Schizophrenia: Review of the Work of Prof Eugen Bleuler. Archives of Neuropsychiatry, 26(3):610-627.

- Lutz, Jakob (1937) Über die Schizophrenie im Kindesalter. Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie und Psychiatrie, 39:335-372.

- Asperger, Hans (1938) Das psychisch abnorme Kind. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 49:1314-1317.

- Despert, JL (1938) Schizophrenia in Children. Psychiatric Quarterly, 12:366-371.

- Kanner, Leo (1943) Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact. Nervous Child, 2:217-250.

- Kanner, Leo (1944) Early Infantile Autism. The Journal of Pediatrics, 25(3):211-217.

- Asperger, Hans (1944) Die ‘autistischen Psychopathen’ in Kindesalter. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten, 117:76–136.

- Bleuler, Eugen (1950) Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. New York: International Universities Press.

- Kanner, Leo (1948) Child psychiatry. Springfield: Charles C Thomas.

- van Krevelen, D Arn (1952a) Early infantile autism. Zeitung für Kinderpsychiatrie, 19:91-97.

- van Krevelen, D Arn (1952b) Een Geval van ‘Early Infantile Autism’. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde, 96:202-205.

2 thoughts on “Historical context of Asperger’s first (1938) autism paper”

Comments are closed.