In each of the last two years I have been involved in a film discussion group run by and for people with an Asperger syndrome or autism spectrum diagnosis. The group has fluctuated in membership between four and twelve people, with a core of continuous members. We have watched predominantly feature films and documentaries in which at least one principal character is explicitly identified as ’autistic’ within the film, in publicity material or according to audiences. Our group has displayed a phenomenal knowledge of cinema, television and relevant links to other art forms such as fiction, graphic novels and computer games with the same characters. The film discussion group has been a positive experience with a good reception.

The enthusiasm of the group and the incredible depth and breadth of knowledge about cinema and media shows a huge wealth of systematic learning while viewing, perhaps at a level that family and others are not aware. Reading ’comics’, playing console games and watching ’kid’s TV’ can have undiscovered depths of meaning for people who have limited opportunities to discuss their particular interests.

I hope this blog post might encourage you to start discussion groups of film, fiction or whatever areas interest you, and I would be pleased offer advice or attend further sessions. I would be especially interested in any public screenings of autism-themed films — the Cork Film Festival screening of “Life, Animated” (http://corkfilmfest.org/events/life-animated/) and panel discussion (which I was thrilled to be part of) was packed, and all the feedback that reached me was incredibly positive.

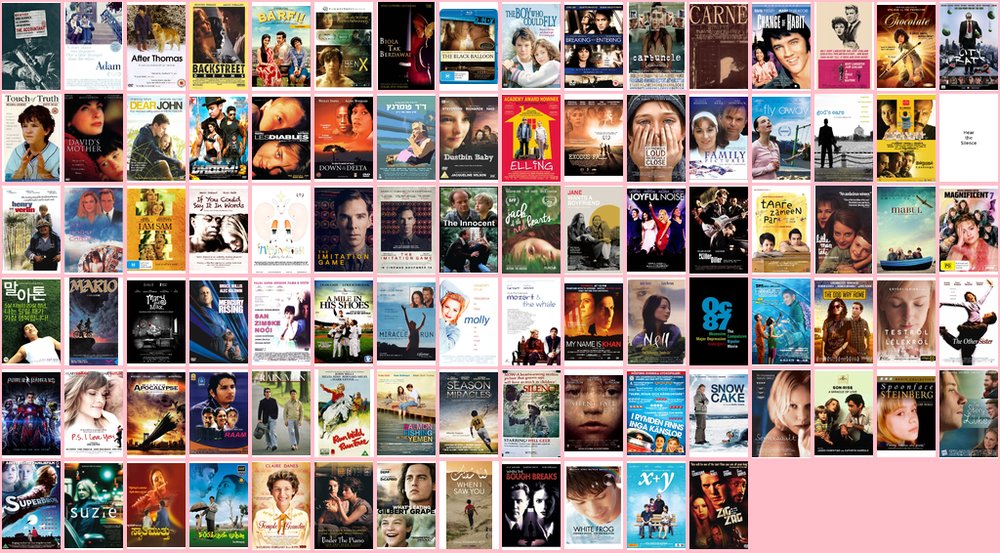

Some initial resources that might help are a Guardian article on “How to start a film club” (https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/sep/12/how-to-start-a-film-club) and a BBC Radio 4 feature on “Running a bookclub” (http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/features/book-club/running-a-club/). You can find a starter list of autism-themed films (http://gallery.stuartneilson.com/index.php?album=Autism-films/Autism-feature-films) and fictional books (http://gallery.stuartneilson.com/index.php?album=ASD-fiction) on my website.

(Thanks especially to those who provided the resources, planning skills and personal support to get our group running, regularly, on time and in a comfortable space).

Introductions

The group is an informal evening event, although we met each other as clients of an Asperger syndrome support service that we all attend. The primary purpose of the group began with discussion of autism in film and the representation of autistic people. Each weekly session starts with a short introduction to the film, followed by the film itself and then an open-ended and often wide-ranging discussion afterwards. Tangents are positively encouraged and have lead to some amazing insights into what films mean to each of us as individuals. Nobody is obliged to contribute, although most have done.

Why films ’about autism’?

I personally set out to explore the identity of people with an autism spectrum diagnosis, especially adults like ourselves, and how autistic people are identified and represented in film. We are a very diverse group of individuals who share a few common characteristics, in different combinations, amongst ourselves, and are more different than alike. Outside our own homes and support services we are largely reduced to identification by the public by popular (mis)perceptions of what the labels ’Asperger syndrome’ or ’autistic’ mean. On occasion we have all been forced to fit an image that comes from “Rain Man” or “The Big Bang Theory”, because these are how most people are familiar with the autism spectrum. This ranges from the fairly benign (“What is his special skill?”) to the damaging (such as being talked about in our own presence as if we can’t understand, or being discouraged away from the arts and into STEM subjects at school).

Films have a great power to shape perceptions of autism, not just reflect reality, and they affect how (or even whether) people receive assessment or appropriate services. Not fitting the popular image of autism can be detrimental — especially for women, people with good verbal skills, non-mathemeticians, or Asperger syndrome combined with a cognitive or reading impairment. Viewing films as a group is a step towards identifying ’good’ and ’bad’ representations, and a step towards collectively endorsing the positive images and rejecting the negative images that shape our lives.

The group has been evolving towards a broader objective of viewing films that members identify with, whether or not there is any reference to autism in the film. Films, like clothes or music, are personal choices that reflect and express identity, so a broader view of films with meaning to individual members is likely to be our next step.

Setting

The setting we have been using is a comfortable, quiet room with a large flat-panel television with a DVD player and USB video. There are enough comfortable armchairs on most evenings, with spare padded chairs if numbers rise, and enough space for us to spread comfortably. Many people have brought a drink or snack because the sessions are long — with an introduction and a discussion they can last three hours or more if we watch a film like “Power Rangers”, with a running time of more than two hours. We switch the main lights off during the film and back on for the discussion session. We have used subtitles on most films, which many people seem to find helpful. At home I watch everything with subtitles on, and I find that I follow the narrative of films and drama far better with the text of the subtitles.

Watching together, like eating together is social and adds to the pleasure of watching a film. I occasionally find cinema quite overpowering, with large crowds, human odours (especially after it has rained), popcorn and snack odours, the sound system volume and (in the newer cinemas) seats containing low-frequency rumble speakers. Even so, my memories of the collective recoil at some of the stunts in “Borat” and the collective shock at one scene in “Jagged Edge” are wonderful and have almost always added to my understanding of my own responses to the scenes. Our relatively small cohesive group meeting in a safe space is about as good as collective viewing can get.

Access to material

As an informal group that is not charging any fees or selling anything (members bring their own food or drink), I assume that we count as non-commercial personal viewing, just as any group of friends meeting privately to watch a film. At least one of use already owns most of the films we have viewed on DVD and we have purchased others on DVD from retail shops or online suppliers. Screenings that are open to the public, or for which any membership fee is charged, would need to observe licensing and copyright conditions carefully.

Our film selections last year included animation, drama, some TV comedy and a historical documentary:

- “Inside Out” (2015)

- “Mary & Max” (2009)

- “Snowcake” (2006)

- A variety of TV series (“The Big Bang Theory”, “Alphas” and “Community”)

- “The Wild Child” (1970)

- “X+Y” (2014)

Our film selections this year included hero and super-hero action films, a biopic, a documentary, drama and one new TV comedy:

- “The Accountant” (2016)

- “Aspergers are Us” (2016)

- “Killer Diller” (2004)

- “Power Rangers” (2017)

- “Run Wild, Run Free” (1969)

- “Temple Grandin” (2010)

- New Netflix TV comedy “Atypical”

Representations of autism

In general, the portrayal of autism on screen is woeful. On-screen autism is conveyed by clichés and stereotypes gathered from earlier film tropes or, in the worst cases, a point-by-point rote-acting of the DSM criteria for an autism diagnosis (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/hcp-dsm.html). We could have played ’autistic bingo’, with a prize for the first person to spot a qualifying set of DSM tick-boxes. Some scenes look like they were scripted from examples in the DSM commentary section, such as “e.g., a toddler strongly attached to a pan; a child preoccupied with vacuum cleaners; an adult spending hours writing out timetables”. There are no films in which autistic people act in autistic roles (other than Jovana Mitic in the Sebian-language “Midwinter Night’s Dream” and Lizzy Clark in the BBC TV drama “Dustbin Baby”). Few films are made under the direction of, or even with direct input from, the experience of autistic people. A couple of startling exceptions are “Temple Grandin”, to which Temple Grandin herself made a large contribution, and “Aspergers are Us”, a documentary featuring the members of an autistic comedy troupe.

While most representations are simply misleadingly stereotypical (e.g. “The Big Bang Theory”), some are harmful in depicting a kind of autism that is unrealistic or therapy that is violent and abusive (“The Accountant”). Real audiences are more often informed about autism through fictional cinema, TV comedy and other media than by contact with a diverse variety of real autistic people. Public and professional interactions with and therapeutic approaches towards autistic people may well be influenced in ways that cause harm or deny opportunity to autistic people. Challenging fictional portrayals is an important form of self-advocacy.

Cinematic quality

I was surprised that most of the group are far more concerned by the screenplay, direction, camera-work, action and pacing of the films than by the representations of autism. As self-confessed film buffs, the group as a whole enjoyed “The Accountant” as a ’good film’ within the genre of action films, with a rounded central character and well-paced action sequences. The misrepresentation of autism and appalling presentation of parental abuse as an effective autism therapy were secondary to these cinematic qualities, and most members have positive anticipations for a sequel of this ’autistic action hero’. The Netflix comedy “Atypical” was also recognized as a potentially ’good series’ in the genre of TV comedy for lively action, good scripting and the depth of plot — despite presenting a highly medicalised view of the central characters life, and traits that seem to be assembled by a psychiatrist quoting the DSM. The problematic portrayals are again secondary to the cinematic qualities, which are more important in gaining recognition. This group feel confident of being able to use topics from these films and TV series in discussions about autism and their own lives.

In contrast, the group was critical of the pacing in “Temple Grandin” and the uneven plotting and character in “X+Y”, and the overall quality of made-for-television films. A poor portrayal in a mainstream cinema release has more value than a sensitive portrayal in a niche or made-for-TV production with limited impact.

The quality of the film as cinema was therefore at least as important, and far more important to some members of our group, than the portrayal of autism.

Knowledge — breadth and depth

The breadth and depth of knowledge about almost every aspect of media was astounding. The super-hero action film “Power Rangers” brought out knowledge about the entire range of English-language Power Rangers TV series, the Japanese series on which they were based and the original Japanese graphic novels in which the characters first appeared. In addition, there was a wealth of knowledge about viewership figures and the funding issues that influenced the TV and film productions, the director’s entire CV and insights into the personal lives of the original TV actors that were incorporated into the latest film production. This last point raised a passionate discussion about identity politics and gender, and how Hollywood appropriates and re-presents gender identity. The new “Power Rangers” production was also compared and contrasted with the 1985 John Hughes comedy “The Breakfast Club”, which blew me away at the wonderful scope of cinematic awareness possessed by group members.

Many of these individual facts might be dismissed as ’trivia’, and spending time watching TV or reading Manga might be dismissed as wasteful time-filling behaviours. This would be to dismiss an incredible quantity and quality of learning that has been experienced by our group members. There are probably few opportunities in life where someone can comfortably express this kind of knowledge and share pleasure with like-minded people with equivalent experience. There are considerable life and employment skills in evidence which are rarely displayed simply for the lack of a relevant and welcoming context to express them.

Reactions

We established early on that we feel old enough and ugly enough to stand up for ourselves, and able to endure (and even to enjoy) ’bad’ representations within ’good’ movies. The one consistent theme that came up was representations of self on screen. I can honestly say there is no autistic character on screen who represents me well — the one I like most is Lisbeth Salander as portrayed by Noomi Rapace in the 2009 Swedish original of “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo”, because I would like to be as confident and effective as her. The 57-year-old narrator, Ray, of Sara Baume’s award-winning 2015 novel “Spill Simmer Falter Wither” is so close to many of my own experiences that I almost felt the author looking over my shoulder as I read it. But in film, sadly, none of us feel that we are represented, either by characters that realistically portray our lives or by autistic actors.

This is very like the erasure of women, Black and Asian people, LGBT+ people and disabled people in portrayal. It is a long time since women were portrayed by boys on stage, as in Shakespeare’s time, although women first gained prominence only in the 17th century through opera and the late 19th century in theatre. ’Blacking up’ is within my own memory (“The Black and White Minstrel Show” was produced until 1978) and ’yellow face’ erasure of Asian characters portrayed by white actors causes regular outrage now (https://thenerdsofcolor.org/2015/06/01/hollywoods-strange-erasure-of-asian-characters/), although the sensitivity of portrayal has climbed up from the depths of Boris Karloff’s “Fu Manchu” or Mickey Rooney’s Yunioshi in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” (http://www.complex.com/pop-culture/2016/11/asian-roles-played-by-non-asian-actors/breakfast-at-tiffanys and society has moved forward from a time when “Mickey Rooney’s bucktoothed, myopic Japanese is broadly exotic” (New York Times review, 1961). Disabled or mentally ill characters are almost always portrayed by actors who are neither disabled nor have the life experience that they are attempting to portray. Hollywood remains a straight, young, white man’s world where all other identities are paid less, employed less, on screen less and have little control over their own image.

Our group was therefore very conscious of self portrayal whenever and wherever it did occur — an accountant thrilled to see the profession on screen in “The Accountant”, Abed’s realistic student experience in “Community”, the bullying we have all experienced in “X + Y”, living alone as portrayed by “Mary & Max”, the sense of ’stage-fright’ that public spaces evoke in “Aspergers are Us” and the workplace dynamics and harassment in “Temple Grandin” are all real experiences that we have had. Some are hard to talk about and film is an effective means of opening dialogue, or at the very least displaying situations that impact our lives.

Sometimes little vignettes from a film can be powerfully moving. Philip’s parents in the 1969 drama “Run Wild, Run Free” are not uncaring or negligent, but their cluelessness and the complete absence of professional support (apart from suggesting he be placed in an institution) leads to a neglected childhood. This would be a tough thing to say to a parent, whereas watching the film together and comparing the adults in Philip’s life to my own childhood and schooling in the 1960s and 1970s, when I was regarded as wilfully defiant, inattentive and insolent (there was no diagnosis of Asperger syndrome then) could have good bonding potential.

Autistic adults (any post-education age) are not common in film, nor are women. The two films with women, both adults, were probably the least similar to any of our collective life experiences. “Temple Grandin” is a wonderful advocate and role, but she is a model and not the model of autism, and we need more diverse representations if people are to be able to recognize themselves on screen. Because they were not like ourselves both “Temple Grandin” and “Snow Cake” were subjected to a level of detailed criticism that some of the other films were spared. In contrast “Power Rangers” contained a consciously diverse range of ethnicity and gender identities, with an excellent performance by RJ Cyler as Billy (Blue Ranger) “an autistic and intelligent loner who is the classic nerd and has become a bully magnet”, a reality many of us have experienced. Billy was also not characterized by savant skills (which are not characteristic of autism), superhuman intelligence or mainframe-power mathematical skills.

So if we are old enough and ugly enough to feel confident of challenging, using and interpreting autism on screen, good or bad, what about other autistic people who do not have our education, verbal skills or comprehensive communicative language? I imagine they feel exactly the same. We all need to see more autism on screen, portrayed or written from life experience of autism, paying autistic actors and accepting their input in decision-making on portrayal.

Women, Black, Asian, LGBT+ and disabled people do not advocate for ’good’ representations of themselves. They want to be on screen, good, bad and ugly — just like the straight, white men.

Future direction

Overall the people who attended seem to have had a positive experience and to have enjoyed the opportunity to talk about individual films and talk about film in general with others who share their passionate interest. The issue of portrayal of autism was interesting, but my initial focus on the representation of autism as the central theme has not been shared equally by everyone in the group. Film and cinematic quality were more important.

In future the group as a whole would be interested in sharing their own film interests — whether or not autism is featured — perhaps with individuals volunteering to present one or more of their own favourite films and presenting their reasons for choosing particular films or genres. The choices of film and personal presentations are likely to be just as useful in expressing autistic identity and self-image, and just as important as affirming or rejecting explicitly autistic identities projected by media portrayals.

I would be thrilled to be involved in other groups, and especially in any form of public screenings, perhaps even an autism film season. Please contact me if you have any ventures underway or would like a guest speaker, panellist etc in your own film or book group. I do not drive and don’t travel well, especially to places or to people I have never encountered before, so meeting in Cork first would be a good first step.

Resources

- Cork Film Festival — http://corkfilmfest.org/

- “How to start a film club” — https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/sep/12/how-to-start-a-film-club

- “Running a bookclub” — http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/features/book-club/running-a-club/

- Autism-themed feature films — http://gallery.stuartneilson.com/index.php?album=Autism-films/Autism-feature-films

- Autism in fiction books — http://gallery.stuartneilson.com/index.php?album=ASD-fiction