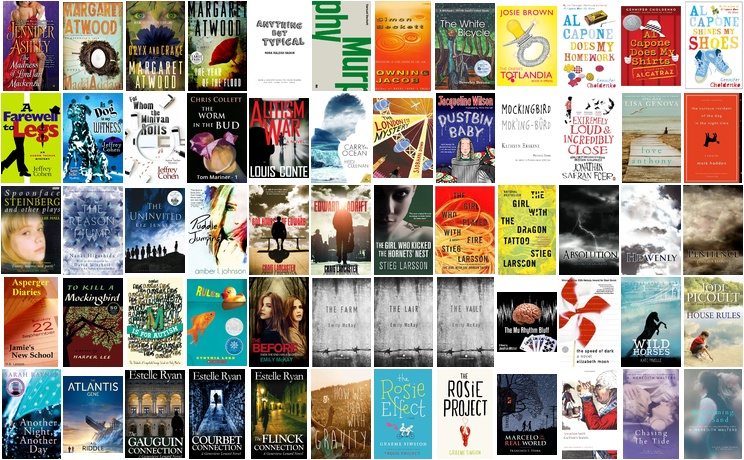

I spent the summer of 2015 reading over thirty of the many, many fiction titles that relate, in some way, to autism. My personal reviews of individual titles will follow in a sorted gallery, where I can continually add and update the collection. Each review includes a link to a longer review in a newspaper or blog and a link to the author’s site, sorted by author surname. These are widely varied titles, from children’s to adults’ fiction, from romance to vampires, and from thrillers to science fiction. Most of these books state or strongly imply that a central character has an autism spectrum diagnosis, or it has been stated in publicity material or related films. The autistic character is not always the lead, and is not always painted positively – both negative and positive characters and events can be equally meaningful representations of most people’s real lives.

My interest in these books is whether they portray autism in realistic ways, or at least in useful ways. A few of the books are unduly negative, inaccurate or both. Some of the books portray life in a way that people with autism can relate to, some portray inspirational role models and some present scenarios that people with autism can use to share their life experiences with others.

Adult content warning

Although some of the books are children’s or young adult’s fiction, there are others with strong adult themes. All of these books could be of interest to a mature adolescent or a mature adult with an autism spectrum diagnosis, or for use in talking about autism. Violence, swearing and explicit sex in a few titles might be offensive or upsetting to some readers.

Diagnosis, identity and public disclosure

In each review I try to identify the age, gender and diagnosis of the character with autism, preferably using the book’s own wording. Some characters are explicitly not diagnosed, some are strongly implied to be “somewhere on the spectrum” and some books state a specific diagnosis of autism or Asperger syndrome. (I have written elsewhere about the non-diagnosis of Professor Don Tillman). For instance Christopher Boone (“The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time” by Mark Haddon) is never stated to be autistic, although publicity and jacket material has identified both autism and Asperger syndrome. It is a rich book about the dislocation of family relationships and Christopher is a rich character, but reading it as a book ‘about’ autism may disappoint, unless Christopher’s life and challenges relate to you – and for many individuals, they will.

Often we ‘know’ that a book is about autism because society tells us that it is so, picking out eccentrics, geniuses and loners as either part of the spectrum’s rich tapestry or, worse, definitive descriptions of autism. Mark Haddon has stated very clearly that Curious Incident “is not a textbook”, but it is a book that works on many levels for many readers. The disclosure of autism is usually explicit somewhere, in publicity material, author interviews and related books or films. Sometimes the exact diagnosis or its accuracy may be left hanging, just as it is in real life.

With authors I take a strict line that diagnosis must have been publicly disclosed by the author, and we have no right to discuss the undisclosed private life of living people. This leaves only three published works of fiction about autism – Naoki Higashida with “I’m Right Here” (a short story in “The Reason I Jump” translated by David Mitchell), Jonathan Mitchell with “The Mu Rhythm Bluff” and the students of Limpsfield Grange School with “M is for Autism”. There are many autobiographical and factual books by people with a public diagnosis of autism, which I intend to cover in two separate posts.

Importance of accuracy in the portrayal of autism

Not all fiction is positive or uplifting, just as real life has negative experiences and depressing times. Not all characters with autism are nice people, just as not all people with autism are nice in real life. Boo Radley is a malevolent presence throughout “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, yet we only meet him and discover what he is really like in the final scenes. It is important that depictions are accurate, or at least are depicting the interaction of autism and life events in a way that readers can relate to. The credibility of autistic characters varies widely, from barely believable to highly realistic.

Some books are included despite having very little to say about autism – Jacob has no presence in “Owning Jacob” by Samuel Beckett, Asperger University makes only the briefest appearance in “Oryx and Crake” by Margaret Atwood and Natalie is the absent sister throughout “Al Capone Shines my Shoes” by Gennifer Choldenko – but they are important in showing that autism affects so many lives. Non-verbal people are, as one would expect, rarely depicted in the first person and most widely as secondary characters in other people’s stories. The bravest exception is Lisa Genova’s channelling of the voice of a non-verbal autistic child in “Love Anthony”, presenting something we might read if a non-verbal child could write to us about their feelings.

Autism presents in widely varying forms, and “if you have met one person with autism, then you have met one person with autism”. I find it hard to relate to some of the characters, for instance Mel in the vampires-and-zombies series “The Farm” by Emily McKay or the uniquely talented Genevieve in “The Gauguin Connection” by Estelle Ryan. I can relate to Hesketh Lock in “The Uninvited” by Liz Jensen, who is equally unusual, but may have limited resonance with other readers. This diversity of portrayals is vital to finding meaning in fiction.

Some books present damaging, inaccurate messages about autism – Jacob in “House Rules” by Jodi Picoult is a sociopathic teenager, written without warmth or care. If we read “Oryx and Crake” by Margaret Atwood as anything other than allegory, then Crake (Glenn) is also a supremely rational, heartless sociopath whose logic takes the world to the brink of destruction. “The Worm in the Bud” by Chris Collett posits a medication for insomnia during pregnancy that causes autism (or something like it) in the unborn children of women taking it, with distorted anti-medication messages throughout – Jamie is quite a realistic character, but it is unfortunate to portray his autism as an injury caused by pharmaceutical negligence. “The Atlantis Gene” by AG Riddle presents a disembodied autism gene over which powerful forces fight, with autistic children reduced to research subjects. These books are worth mentioning for completeness, and to include the diversity of genres in which autism is used as a plot device.

It is worth taking to heart Neil Gaiman’s statement that “there is no such thing as a bad book for children”, echoing Oscar Wilde’s statement that “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.” Books about autism can be helpful if they are well-written, engaging and resonate with their readers. The best autism fiction has the potential to bring greater understanding between those who have and do not have autism.

Academic and teaching interest

Some literature has useful messages that have been linked with autism. Sometimes these books predate the diagnostic categories of autism, by decades or by centuries, but they contain scenarios that are good discussion points. I like the characterisation of Murphy, whose lunch is such a fantastic description of rigid thinking and routine in “Murphy” by Samuel Beckett – I illustrated this episode in my post on autism in fictional and factual books and film. Jonathan Swift describes social friction based on the ‘othering’ of different people throughout “Gulliver’s Travels” by Jonathan Swift, which brought to life his real-world experience of social attitudes to mental illness and the display of ‘freaks’ in shows. We continue this tradition, perhaps more subtly, by displaying ‘special skills’ without necessarily considering the autistic person who is made to perform (in both fiction and life).

Where these portrayals and messages make a contribution to understanding autism, or helping people with autism understand the world, they are a welcome addition. It does not particularly matter if the depiction is a diagnostically complete and accurate one, so long as it does not mislead.

Life-enhancing fiction

Some of these books had a positive impact on me as an individual, because they speak about characters and events that I can identify with. These life-enhancing books are not always ‘positive’, describing very difficult events and (sometimes) very negative character traits that are, nevertheless, useful to me. These are my favourites:

- Anthony, the voice of a non-verbal child with autism, is a particularly moving character in “Love Anthony” by Lisa Genova.

- “The London Eye Mystery” by Siobhan Dowd presents 12-year-old Ted investigating the disappearance of a relative from a locked room, attempting to be taken seriously by his sister, parents and adults.

- Oskar Schell in “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close” by Jonathan Safran Foer is working through the difficult loss of his father, fear of the outside world and establishing intimacy with his family.

- Lisbeth Salander in “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” by Stieg Larsson is a wonderful model of a young woman overcoming a horrendous childhood, daily battles with social convention and a society that is routinely violent towards women.

- “M is for Autism” is a beautifully illustrated collaborative fiction project by the students of Limpsfield Grange School, detailing the events in the life of a teenage girl leading up to a diagnosis with autism.

- In “The Rosie Project” by Graham Simsion Don Tillman is an older man facing challenges navigating a complex and devious social world.

- Flynn Hendrick is a 22-year-old virgin in “Reclaiming the Sand” by A Meredith Walters, dancing a romantic ballet with a partner totally unlike himself.

It happens that Lisbeth and Don are explicitly not diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. The diagnosis is merely implied with Oskar and diagnosis is not central to the portrayals of Ted and Flynn. These are all real people, struggling with real challenges that affect everyone (autistic or not), embedded in stories that are interesting, funny, sad and thrilling.

Autistic people want to be portrayed in fiction and to read fiction that relates to their own lives, not as objects of curiosity, but because the story they inhabit is interesting.

You can access the gallery of reviews here. The books are sorted by author surname and then by title.

Your thought about the “Importance of accuracy in the portrayal of autism” is very true.

I could not agree more with you.