We usually talk about autism and many other aspects of our everyday experience as a disorder, with all the connotations that medical interpretations bring – of disease, individual tragedy and suffering. Autism is a mental disorder within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), a dyad or triad of impairments, a learning or language delay and a set of deficits. All of these words medicalize the everyday experience of people with autism. Some elements of life — particularly the minutes spent in consultation with a doctor — are medical, but as soon as you leave the consultation room, you return to being a child, a boy, a girl, a person, or whatever else is your primary identity. Taking on the belief that you are diseased and in need of cure (especially when there is no cure, nor any immediate prospect of cure for autism) can be very damaging to self-esteem.

Disability is a social condition

In 1975 Vic Finkelstein and the Union of Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) wrote:

“Fundamental principles to which we are both in agreement:

disability is a situation, caused by social conditions, which requires for its elimination,

-

(a) that no one aspect such as incomes, mobility or institutions is treated in isolation,

-

(b) that disabled people should, with the advice and help of others, assume control over their own lives, and

-

(c) that professionals, experts and others who seek to help must be committed to promoting such control by disabled people.”

Vic Finkelstein and others in the Union of Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) irretrievably split the disabled from their non-disabled supporters (professional and academics of the Disability Alliance), fracturing the collective of the Disabled Income Group. Their demand to assume control over their own lives implicitly charges professionals, including professional allies, of conscious or unconscious complicity in oppression of disabled lives.

That was in 1975, and forty years later we still have a situation in which all major decisions about the lives (not just the medical treatment) of autistic people are being made by professionals and experts.

Impairment is NOT disability

Impairment is a medical issue and correct medical labelling is helpful. Carrying that label into the rest of life can itself be disabling. Locating the problem of disablement in an external process is liberating. The problem is not located in the individual or the (medical) impairment. The problem is located in exclusion and lack of accommodation.

“Thus we define:

- impairment as lacking part of or all of a limb, or having a defective limb, organ or mechanism of the body; and

- disability as the disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by a contemporary social organisation which takes no or little account of people who have physical impairments and thus excludes them from participation in the mainstream of social activities.

- Physical disability is therefore a particular form of social oppression.”

— UPIAS (1975, p20) “Fundamental Principles of Disability”

Impairment does not necessarily lead to disablement (social or other exclusion). The process of disablement is a social choice – it is too expensive, too uncomfortable or too inconvenient to be inclusive – and disability is not intrinsic to the individual. For instance, in our society, poor eyesight is mostly accommodated. Compare these circumstances in which the context affects the same impairment in different ways:

Not disabled

- Corrected vision using glasses or contact lenses

- Assisted hearing

- TV, film, theatre and opera (or legal proceedings) supported by sign language and subtitles or surtitles

- Controlled diabetes and availability of safe food choices

- Suitable employment

- Appropriate adult education

Impaired & Disabled

- No access entertainment, or entertainment that requires a specific level of vision and hearing acuity

- Noisy environments and shops or banks with no induction loop hearing assistance

- Communication through speech alone in theatre, the Dáil, news or court proceedings

- Uncontrolled diabetes or lack of adequate healthcare and safe food choices

- No available employment

- No adult employment or training

We can get far too hung up on the words we use – Twitter and Facebook are cautionary examples of well-intentioned people at war over language, and forgetting the good deeds they set out on. Sometimes all the good people seem to be so busily engaged in Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) that a unified voice on important issues is absent.

“If we are not careful we will spend all of our time considering what we mean by the medical model or the social model, or perhaps the psychological or more recently, the administrative or charity models of disability. These semantic discussions will obscure the real issues in disability which are about oppression, discrimination, inequality and poverty.” — Mike Oliver (1990, p2)

Rory O’Neill (‘he’) and homophobia

Rory O’Neill is a (reluctant) gay rights activist from Ballinrobe, County Mayo who appeared on The Saturday Night Show with Brendan O’Connor on 11 January 2014. He described people who make a living out of being horrible and mean about gays, who were then characterised as ‘homophobic’ by the Brendan O’Connor. The discussion was removed from the RTÉ Player, but preserved for posterity at dailymotion.com – the ‘homophobic’ comments begin at about 10’30″.

There is a transcript of the words at (of all places) The American Conservative. A contemporary news account is Ignorance Isn’t Panti Bliss by Matthew Mulligan, Thursday, January 16, 2014.

RTÉ apology, withdrawal of the video and compensation payment

RTÉ decided to apologize. The statement on air was “Now, on the Saturday night show two weeks ago comments were made by a guest suggesting the journalist and broadcaster John Waters, Breda O’Brien and some members of the Iona Institute are homophobic. These are not the views of RTÉ and we would like to apologise for any upset or distress caused to the individuals named or identified. It is an important part of democratic debate that people must be able to hold dissenting views on controversial issues.” — Brendan O’Connor, 25 January 2014.

The people named threatened legal action and RTÉ took down that section of the interview from the RTÉ Player and, in addition to the public apology, RTÉ paid €85,000 compensation to John Waters and Breda O’Brien of the Irish Times, and David Quinn, Dr Patricia Casey, Dr John Murray and Ms Maria Steen of the Iona Institute. (Independent).

The RTÉ compensation payment was debated in the Dáil, 6 February 2014.

My personal view is that €85,000 (about 2 cents per person in Ireland) was extremely good value for money in enabling the debate, public discussion, engagement and increased social understanding of oppression and acceptance. Not to mention the humiliation and loss of reputation of those by those who chose to be identified as homophobes in the firestorm.

“The Pink Police State” (Rod Dreher)

The international coverage of Irish affairs was amazing. One little reactionary gem (the source of the forbidden transcript above) labelled Ireland The Pink Police State, claiming that “Gay rights fundamentalists have been working hard to push a newspaper columnist who happens to be Catholic to the margins. Rory O’Neill, a Dublin drag queen who performs under the name Pandora Panti Bliss, went on live national TV to denounce O’Brien and others.” — Rod Dreher, 24 January 2014, www.theamericanconservative.com

A senator echoed these sentiments in the official record of the Dáil, “I have a question for the Leader. Can we have a debate on freedom of speech with the Minister for Communications, Energy and Natural Resources? Can we deal with these dangerous, vicious elements in the gay ideological movement? I appeal to those more reasonable voices …” — Senator Jim Walsh, Seanad, 5 February 2014

Pantigate and Panti Bliss (‘she’)

Panti Bliss is Rory O’Neill’s stage persona. She is Ireland’s foremost drag queen. Neither Rory O’Neill nor Panti Bliss apologised along with RTÉ, and instead Panti Bliss delivered the “Noble Call” at the Abbey Theatre on 1 February 2014 (sampled in the record “The Best Gay Possible — Oppressive Dance Mix” by The Pet Shop Boys, 2014). She took her stage show “High Heels in Low Places” on a national tour through 2014 and 2015, with a film ‘Queen of Ireland’ in 2015.

Oppression is a shared experience

Panti “got thousands of emails from gay people” but also from “people in wheelchairs and with autism”, and from women. “Anybody who feels oppressed has the same experience,” says O’Neill. For him, one of the most important legacies has been how it has allowed gay people to start conversations about homophobia within their families. “Most gay people do not go to their families and say ‘Oh somebody called me a faggot today’,” he says. “[So] I get a lot of gay people saying ‘Thank you’ for that.” — Independent

Most disabled people do net talk to their families about the daily events that oppress them. It does not matter what kind of oppression people felt, the words in the “Noble Call” seem to have spoken for many people who heard it, who felt that Panti Bliss was expressing their own reactions to their own specific experiences of oppression.

Social acceptance is sometimes or always absent for some groups of people

“This week in the Oireachtas we were told as gay people that it is a matter of ‘social re-engineering’ by the ‘gay ideological movement’. I am quoting from a Member of the Seanad. I speak not just as a gay person but as a member of society who wants to be treated equally. I have been beaten, spat on, chased, harassed and mocked, like Deputy Lyons, because of who I am. I was born with a gift given to me. I have spent most of my life struggling and am finally at a place in my own country, which I love, to be accepted.” — Jerry Buttimer TD, Dáil 6 February 2014

Deputy Jerry Buttimer (Fine Gael TD, Cork South Central) said in the Dáil debate “I fully accept the Minister’s position regarding involvement in the day-to-day management of RTE. However, we as a society and this Parliament have a role to play in the national broadcaster. RTE got it completely wrong. It folded in its tent . This week in the Oireachtas we were told as gay people that it is a matter of “social re-engineering” by the “gay ideological movement”. I am quoting from a Member of the Seanad. I speak not just as a gay person but as a member of society who wants to be treated equally. I have been beaten, spat on, chased, harassed and mocked, like Deputy Lyons, because of who I am. I was born with a gift given to me. I have spent most of my life struggling and am finally at a place in my own country, which I love, to be accepted. The support from my colleagues in this House and from the Ceann Comhairle is a demonstration of how our society has come forward, but in a tolerant, respectful debate I will not allow people who spout hatred and intolerance to go unchecked.” — Dáil, 6 Feb 2014.

(See also a contemporary news report Buttimer and Panti drown out empty rhetoric in homophobia debate — 8 February 2014).

The Equal Status Act 2000 and other legislation prohibits discrimination

Legislation in Ireland recognizes and prohibits discrimination between people on specific grounds. The nine discriminatory grounds are:

- One is male and the other is female (“gender”),

- Different marital status (“marital status”),

- One has family status and the other does not, or has a different family status (“family status”),

- Different sexual orientation (“sexual orientation”),

- Different religious belief, or one has and the other has not (“religion”),

- Different ages (“age”),

- One is a person with a disability and the other either is not, or is a person with a different disability (“disability”),

- Different race, colour, nationality or ethnic or national origins (“race”),

- Member of the Traveller community (“Traveller community”)

The ‘Other’ is interchangeable in excluding people

People who wish to ‘Other’ an individual or group are able to exploit the grounds interchangeably — for instance a group of young men who have been drinking will shout ‘freak’, ‘weirdo’, ‘queer’, ‘feck off back to your own country’ interchangeably according to circumstances.

In my working life I have had comments from male colleagues to be careful talking to a new female colleague because “She is a lady of a certain age, so she is sensitive”, “She is young and lacks confidence, so she is a little sensitive”, “I think she is frigid (or a lesbian), so she is a little sensitive”, “She is foreign, so she is a little sensitive”. All of these comments are matey, all-blokes-together exclusion of women from the inner circle. They could be (and are) applied in similar ways to foreigners, Travellers, people with a history of mental illness and disabled people. The grounds of ‘Othering’ are not themselves as important as the act of exclusion. The purpose of the bigot or Otherphobe is to create a sense of distance and exclusion.

The US presidential candidates have publicly linked mass shootings with mental illness. One group has set up a web presence for “Families Against Autistic Shooters”. The temperate US presidential candidates have remained silent in debate when the intemperate have made these remarks.

The reluctant activist

Panti Bliss has described herself as an accidental national hero and reluctant activist: “I accept that I opened up a conversation, and I’m proud of that,” he says, “but it’s easy for people to over-estimate my contribution. I’m visible, but I know many people who have dedicated years of their lives to this, who campaigned around the clock, holding meetings at six in the morning, taking calls, making sure canvassers were on the streets. They are the people who should get the praise.” (Galway Advertiser)

In High Heels in Low Places she said “I don’t know anything about disability, or being in a wheelchair. I don’t know anything about autism. But I had letters from people thanking me for talking about their experiences of oppression.”

Are we all obliged to be ‘reluctant activists’ in societies that exclude ourselves or people we advocate for?

When we do this — like Vic Finkelstein — are we in danger of alienating our key workers, psychiatrists, teachers, parents and others who currently exercise decision-making on behalf of people with autism? If our service provider is the only service provider (an HSE psychiatrist, for example), is activism likely to result in a loss of service? Will people in a position of power over us use coercion (apologies, withdrawal of service, the threat of therapies we fear, such as ECT or antipsychotics) to obtain consent to their decisions?

If we stand up, potentially alone, against bullying and harassment in school or workplaces, are we going to be the targets of even more unwelcome attention?

“Carry the Ocean” by Heidi Cullinan

“Carry the Ocean” by Heidi Cullinan is a young adult romance featuring a love affair between an autistic man and a depressed man:

- Emmet is autistic and speaks bluntly about his impairments, lifelong disability and the attitudes of others

- Jeremey is hospitalized due to clinical depression and panic disorder, an acquired disability

Both sets of parents react badly to the affair, in different ways. Emmet’s father tells his largely supportive mother “You can’t tell him he’s as normal as everyone and then act like he’s retarded [when you disagree with a life-choice he makes]”

There are multiple, interacting grounds of discrimination. The ‘retarded boy’ is first accused of a non-consensual sexual assault on the ‘vulnerable younger boy’. The ‘mentally unstable’ boy is then accused of ‘taking advantage of the retard’. When both boys confirm that their contact was consensual, both sets of parents collude in keeping them apart. Perhaps it is a phase they are going though, and certainly they are not capable of making the decision for themselves. The later tolerance of their contact is not equivalent to acceptance (e.g. that disabled people or gay people have relationships of equal value). Some is not ‘badly’ intentioned, but based on patronising views that these two people need to be protected and cosseted, from themselves as well as external threats. The views do not accept them as self-actualizing decision-makers in their own life choices.

“People saw us walking down the street to the grocery store or wandering the aisles of [the supermarket] and acted as if we were escapees from the Island of Adorable, puppies dressed up in people clothes. Like we weren’t really boyfriends, like we were fake.”

Tolerance is not the same thing as acceptance. Tolerating the cute, trick-performing autistic person does not translate into (and may prevent) acceptance of autonomous capacity to make life choices.

The Best Gay Possible

“Have you ever been on a crowded train with your gay friend and a small part of you is cringing because he is being SO gay and you find yourself trying to compensate by butching up or nudging the conversation onto ‘straighter’ territory? This is you who have spent 35 years trying to be the best gay possible and yet still a small part of you is embarrassed by his gayness.

And I hate myself for that. And that feels oppressive. And when I’m standing at the pedestrian lights I am checking myself.”

— Panti Bliss, “The Noble Call”

- In psychology, the superego reflects criticisms, prohibitions, inhibitions and other rules of the culture in which we live

- Introjection is the process of replicating behaviours and characteristics, absorbing cultural norms into individual behaviour

- ‘Checking yourself’ for signs of looking gay, mad, autistic or disabled is an introjection of society’s discomfort with or hatred of those signs

- Panti Bliss says she hates herself, identifying her ego with the hated characteristics

- Constant vigilance over appearance and anticipation of negative reaction is fatiguing — even if the negative events are rare, the vigilance is continuous

- It is said that you never hear the bullet that kills you, or see who threw the brick that fells you, but the (internally conceived, or remembered) threat of an adverse event causes continuous fear and fatigue

Moderating reactionary responses to the Other – “Recognize your tendencies and work on that”

What Rory O’Neill actually said on RTÉ was a nuanced description of homophobia, cautioning against the impact that the words have on people accused of prejudice and discrimination.

“The problem is with the word ‘homophobic’, people imagine that if you say “Oh he’s a homophobe” that he’s a horrible monster who goes around beating up gays, that’s not the way it is. Homophobia can be very subtle. It’s like racism is very subtle. I would say that every single person in the world is racist to some extent because that’s how we order the world in our minds. We group people. It’s just how our minds work, but you need to be aware of your tendency towards racism and work against it. And I don’t mind, I don’t care how you dress it up if you are arguing for whatever good reasons or whatever your impulses, because you’re worried about society as a whole and all this rubbish. What it boils down to is if you’re going to argue that gay people need to be treated in any way differently than everybody else or should be in anyway less, or their relationships should be in anyway less then I’m sorry, yes you are a homophobe and the good thing to do is to sit, step back, recognise that you have some homophobic tendencies and work on that.”

— Rory O’Neill’s original RTÉ comments

The Social Model is not a personal attack

Almost identical sentiments were expressed by Mike Oliver in 1990 about the risks of alienating medical professions when discussing the oppressive impact of medicine upon disabled people:

“The problem arises when doctors try to use their knowledge and skills to treat disability rather than illness. Disability as a long-term social state is not treatable and is certainly not curable. Hence many disabled people experience much medical intervention as, at best, inappropriate, and, at worst, oppression. This should not be seen as a personal attack on individual doctors, or indeed the medical profession, for they, too, are trapped in a set of social relations with which they are not trained or equipped to deal.

The problem is that doctors are socialised by their own training into believing that they are ‘experts’ and accorded that role by society. When confronted with the social problems of disability as experts, they cannot admit that they don’t know what to do. Consequently they feel threatened and fall back on their medical skills and training, inappropriate as they are, and impose them on disabled people. They, then appear bewildered when disabled people criticise or reject this imposed treatment.”

— Oliver (1990, p4)

Excluding the ‘Other’ — what ‘looks gay’?

“Have you ever been standing at a pedestrian crossing when a car drives by and in it are a bunch of lads, and they lean out the window and they shout “Fag!” and throw a milk carton at you?

Now it doesn’t really hurt. It’s just a wet carton and anyway they’re right — I am a fag. But it feels oppressive.

When it really does hurt, is afterwards. Afterwards I wonder and worry and obsess over what was it about me, what was it they saw in me? What was it that gave me away? And I hate myself for wondering that. It feels oppressive and the next time I’m at a pedestrian crossing I check myself to see what is it about me that “gives the gay away” and I check myself to make sure I’m not doing it this time.”

— Panti Bliss, “Noble Call”

What ‘looks autistic’?

Autistic people also know that their behaviour can be embarrassing to other people and attract negative comment. Many autism therapies actively teach or enforce ‘normal’ behaviours to replace or disguise:

- Socially inappropriate behaviours

- Lack of eye-contact

- Unusual speech prosody

- Limited facial expressions, hypotonia or unusual posture

- Echolalia, palilalia, pedantic speech

- ‘Non-functional’ routines (adaptive and maladaptive sensory regulation)

- Perseveration, obsessions, intense interests

- Stimming, spinning, hand-flapping

- Toe-walking

Autistic people know that you can’t teach body language. It looks fake, and (being failed ‘normal’) is worse than being authentically different.

The dangers of looking Autistic in front of police

One blog, amazingadventuresautism.blogspot.com, discussed the brutality of US police forces on 15 April 2015:

I had a chat with my son. I told him that if he is confronted by police he must:

- do what they say — put your hands up, put your hands behind your back, let them put handcuffs on you, get in their car — even if you don’t know why;

- do his best to speak aloud, even if he feels like he can’t;

- try not to stim;

- try to point his face in the direction of their face;

- not yell.

He asked, “is it OK to ask what I did wrong?” I had to say, “probably not”, probably the only safe thing to say is “I am Autistic. I need help.”

You might think this is an over reaction. But Autistic people are way too often hurt by police who do not understand how to help someone who does not have the ability to advocate for themselves in the way the police are expecting.

This is like telling girls and women to dress down and not attract unwelcome attention from sex pests.

Looking the wrong kind of disabled

Lisa Hammond (Donna Yates in EastEnders) is 4ft 1in and has pseudoachondroplasia with joint hypermobility. She can stand and walk (with pain) and uses a wheelchair

Lisa Hammond (Donna Yates in EastEnders) is 4ft 1in and has pseudoachondroplasia with joint hypermobility. She can stand and walk (with pain) and uses a wheelchair

“I’ve been shouted at. I’ve had people say, ‘Oi, why are you in a chair when you were walking on EastEnders last night?’ It makes me sad that people can have such closed minds. People always think I’m this feisty girl and I can hold my own but in those moments you just don’t think of anything to say. It’s shock and disbelief. I have to laugh it off.” (OK)

Public expectations of how disabled people should behave are often wrong. The image of autism is a little boy, or a withdrawn genius. Behaving outside the stereotype can be met with extreme prejudice. For instance in the 2011 NDA survey of public attitudes, 52% of people did not agree that people with autism have the same right to sexual relationships; 63% did not agree they should have children; many were uncomfortable with the propsect of a colleague with autism or ID, citing “Personal discomfort, Suitability of work or work environment, Behavioural concerns, Safety concerns for person with disability, Safety concerns for self or others, More work for self or other work colleagues, Having to make accommodations around the workplace”; and many were uncomfortable at the prospect of having neighbours with autism or ID.

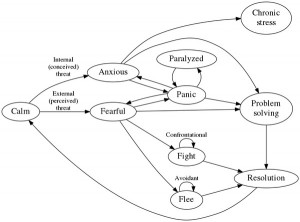

Fight-or-flight to responses to external (perceived) and internal (conceived) threat

If we distinguish between feeling ‘fearful’ in response to an external, perceived threat and ‘anxious’ in response to an internal, conceived threat, the available responses are more limited for anxiety. If you perceive (e.g. see or hear) some drunk lads looking for trouble, you can stand up to them or cross the road to avoid them (fight or flee). You can problem solve the meaning of the threat (e.g. choose to ignore their words). Sometimes both fear and anxiety tip into panic, or paralyzing panic.

You can’t fight or flee from a conceived threat — you have to problem-solve and use logic, otherwise the consequence is chronic stress (and depression, clinical anxiety and panic attacks). Panic attacks, like sensory meltdowns, are acutely embarrassing experiences for adults with autism. The public loss of control can be perceived as bad behaviour, deviance or a threat — security staff or others may worsen the situation.

Anxiety, hypervigilance and paranoia

- Is anxiety a comorbidity or a core feature of autism?

- Does ‘checking yourself’ make it become a core feature in adolescents and adults?

- Hypervigilance is always on, even when there is no threat, with the appearance of paranoia and ideas of reference

- A vicious cycle: anxiety, hypervigilance and ideas of reference feed one-another

- The hot-cross-bun model (emotion — thoughts — behaviour — physiological)

My own behaviour is sometimes perceived to be ‘different’ and it takes very little ‘difference’ to atttract negative attention, especially from drinkers. They are out to abuse someone, anyone, with the slightest devaition from their perception of ‘normal’. I have been verbally abused as a ‘freak’, ‘weirdo’ and ‘queer’, and told to ‘feck off back to your own country’, I have been spat at, and have had (unopened) beer-cans and boots thrown at me and I have had my property vandalized. The (internally conceived) fear that I will not see who throws the next object is always present, even when I am safe from (external) threats. You can’t run away from your thoughts.

The hot cross bun model of anxiety can help with managing anxiety. The important take-away message of the hot cross bun model is that any of the links (between thoughts, emotions, physiology and behaviour) can be cut. For any one person or in any specific context some links are easier to access and cut than others.

Owning your label – educational and medical professionals devalue the essential identity of autistic people

Professionals, experts and educators currently own and control the labels of autism. They direct life, education, interventions, employment and future research. They do so from a deficit model in which autistic people are disordered and Other than normal.

“The devaluation of people with autism also impacts basic research goals. Even as researchers in other areas of disability have replaced the expectation of institutional solutions with the normalisation paradigm (Chappell, 1992), and then replaced normalisation with models like social-role valorisation, inclusion and empowerment, much education research continues to hold out making children with autism ‘indistinguishable from their peers’ (Lovaas Institute, 2007) as an appropriate goal for interventions.”

— Mitzi Waltz (2014, pp355-356)

Who owns homophobia?

Panti Bliss described a surreal situation in which people like Breda O’Brien appropriated and inverted the language of oppression. They took ownership not merely of oppression, but of the language of oppression and its potential for liberating oppressed lives.

“And for the last three weeks I have been lectured by heterosexual people about what homophobia is and who should be allowed identify it. Straight people — ministers, senators, lawyers, journalists — have lined up to tell me what homophobia is and what I am allowed to feel oppressed by. People who have never experienced homophobia in their lives, people who have never checked themselves at a pedestrian crossing, have told me that unless I am being thrown in prison or herded onto a cattle train, then it is not homophobia.

And that feels oppressive.”

— Panti Bliss, “Noble Call”

The medicalization of everyday experience

The deficit model is more than labelling impairments, it is a lens through which the person is distorted. If we look through a telescope at the constellation of the Unicorn (Monoceros), we do not imagine for an instant that we are seeing a real unicorn. We don’t imagine that the stars star Alpha Monocerotis is part of a unicorn, or an essential feature of real unicorns. And yet when a child is labelled with an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis, every aspect of that child’s life is seen through the distorting lens of the expected autistic. The child is expected to conform in behaviour and life trajectory according to the concept of an autistic life.

A half a century ago, Thomas Szasz made this comment about the negative impact of medical progress on the people whose lives were medicalized:

“In the initial decades of this century much was learned about epilepsy. As a result physicians gained much better control of the epileptic process (which sometimes results in seizures). The desire to control the disease, however, seems to go hand in hand with the desire to control the diseased person. Thus, epileptics were both helped and harmed; they were benefitted insofar as their illness was more accurately diagnosed and better treated; they were injured insofar as they, as persons, were stigmatised and socially segregated … It has taken decades of work, much of it still unfinished, to undo some of the oppressive social effects of ‘medical progress’ in epilepsy, and to restore the epileptic to the social status he enjoyed before his disease became so well understood. Paradoxically then, what is good for epilepsy may not be good for the epileptic.”

— Szasz (1966, p453)

And you could substitute “what is good for autism is not good for the autistic individual”. (Abraham Maslow wrote that “If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to treat everything as if it were a nail”, which is what some counselling, medicine and psychiatry feels like at the receiving end).

Neurodiversity and the autistic distinction

Sick people need cures. The parents of sick children feel a burden to cure their offspring, and guilt are their inability to effect a cure (along with guilt for all the imagined decisions that might have lead to autism).

“Assertions that autism can and must be ‘cured’ create unrealistic expectations, promote the exploitation of parents made desperate by dire predictions, and perpetuate a climate of negative judgment towards children and adults who are not or do not strive to become “indistinguishable from their peers,” those who look and behave like the autistic people that they are. The insistence that autistic citizens must modify harmless idiosyncrasies for the comfort of others is unreasonable and oppressive. Such idiosyncrasies often serve a productive purpose for the autistic person. Placing the burden of adaptation on autistic citizens only serves the purpose of enabling others to avoid the discomfort of confronting their own fears, their vulnerability, and their destructive attitudes towards difference.”

— Kathleen Seidel (2014, www.neurodiversity.com

Different models of ‘disability’

“The British social model therefore contains several key elements. It claims that disabled people are an oppressed social group. It distinguishes between the impairments that people have, and the oppression which they experience. And most importantly, it defines ‘disability’ as the social oppression, not the form of impairment.

North American theorists and activists have also developed a social approach to defining disability, which includes the first two of these elements. However, as is illustrated by the US term ‘people with disabilities’, these perspectives have not gone as far in redefining ‘disability’ as social oppression as the British social model. Instead, the North American approach has mainly developed the notion of people with disabilities as a minority group, within the tradition of US political thought.”

— Shakespeare and Watson (2002)

You cannot be a person ‘with’ a disability in the perspective of the Social Model

- Disabled people are an oppressed social group

- Impairments and disability are separate

- ‘Disability’ is defined as social oppression, not impairment

— Shakespeare and Watson (2002) - People become ‘disabled’ through a social process of disablement

- Can you be a person ‘with’ autism? (Pure medical model)

- Is autism not an impairment?

- Is autism not intrinsic? (e.g. do other people create the concept of autism around you?)

In the British Social Model of Disability, the impairment is a tangible medical issue. Disablement excludes impaired people from participation.

In the North American approach, disability (or autism) is seen as identity of a minority group.

Neurodiversity, language and identity

- Accepting or rejecting ‘disease’, ‘illness’, ‘disorder’, (especially the DSM definition of autism as a ‘mental disorder’) and other medical terms, whenever used outside a medical context

- Accepting or rejecting the label ‘disabled’ (NB: claiming ‘disability’ may be a prerequisite for legal protection under disability legislation)

- Neurodiversity encompasses neurotypical (NT) and neurodivergent (ND) people

- Autistic (from autos + istic) — means oriented inwards, to inward self

- Allistic (from allos + istic) — means oriented socially, towards others

- Identity-first language and person-first language (PFL and IDFL) are choices

- Disabled person (IDFL) versus person with a disability (PFL) – implies social oppression, in the Social Model of Disability

- Autistic person (IDFL) versus person with autism (PFL) – imples autistic identity is primary, in the North American model of minority inclusion

Temple Grandin

When we consider the goals of most medical interventions – the cure and prevention of disease – what happens to the autistic? And what are the consequences for humanity?

“What would happen if the autism gene was eliminated from the gene pool? You would have a bunch of people standing around in a cave, chatting and socializing and not getting anything done.”

— Temple Grandin, The Way I See It: A Personal Look at Autism & Asperger’s

Links and reading

- Rory O’Neill on the Saturday Night Show https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R0-y9ZqiY90

- Panti Bliss delivering “The Noble Call” at the Abbey Theatre https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WXayhUzWnl0

- Attwood, Karen (2015) “Drag queen Panti Bliss on the Irish same-sex marriage referendum, international fame and the changing gay scene”. Independent, 11 April 2015.http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/comedy/features/drag-queen-panti-bliss-on-the-irish-same-sex-marriage-referendum-international-fame-and-the-changing-10168417.html

- Connolly, Shaun (2014) “Buttimer and Panti drown out empty rhetoric in homophobia debate”. Examiner, 8 February 2014.http://www.irishexaminer.com/viewpoints/columnists/shaun-connolly/buttimer-and-panti-drown-out-empty-rhetoric-in-homophobia-debate-258117.html

- Cullinan, Heidi (2015) ”Carry the Ocean”. Cincinnati, OH: Samhain Publishing. http://www.heidicullinan.com/Carry_the_Ocean

- Grandin, Temple (2008) The Way I See It: A Personal Look at Autism & Asperger’s. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons.

- NDA (2011) A National Survey of Public Attitudes to Disability in Ireland http://nda.ie/Publications/Attitudes/Public-Attitudes-to-Disability-in-Ireland-Surveys/Public-Attitudes-to-Disability-in-Ireland-Survey-2011.html

- Oliver (1990) “The Individual and Social Models of Disability”. http://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/

- Seidel, Kathleen (2004) “The Autistic Distinction”. http://neurodiversity.com/autistic_distinction.html

- Shakespeare and Watson (2002) “The social model of disability: an outdated ideology?”. http://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/

- Szasz, TS (1966) “Whither Psychiatry” Social Research, 33(3):439-462.

- UPIAS (1975) “Fundamental Principles of Disability”. http://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/

- Waltz, Mitzi (2014) “The relationship of ethics to quality: a particular case of research in autism”. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 30(3):353-361.