Fictional films and books about autism

What do people write about when they are writing about “autism”?

Autism is the disease of our age. Susan Sontag introduced “Illness as Metaphor” in 1978, identifying tuberculosis as the disease of the 19th century and cancer as the disease of her own time. HIV and AIDS are the disease of the decade afterwards. Autism is a metaphor for current global concerns – all our fears of Pollution, Viral pandemics, Political aggression, Terrorism, Internet addiction and Natural disasters are encapsulated in ‘autism’ as a metaphor.

People often write “about” autism, using it as a plot device or to add depth to a (usually another) character. Occasionally people write about autism as a lived experience. Only rarely is the lived experience portrayed in film or by actors with autism.

- Are people with autism Character (with agency) or helpless Baggage?

- Is autism being used as a metaphor, e.g. for solipsism?

- Is the experience of living with autism represented?

- Do people with autism direct the narrative?

- Are autistic roles played by people with autism?

- Is it possible to modify a Bechdel Test for autism in fiction?

(For a more detailed discussion see Hacking (2010) “Autism Fiction: A Mirror of an Internet Decade”)

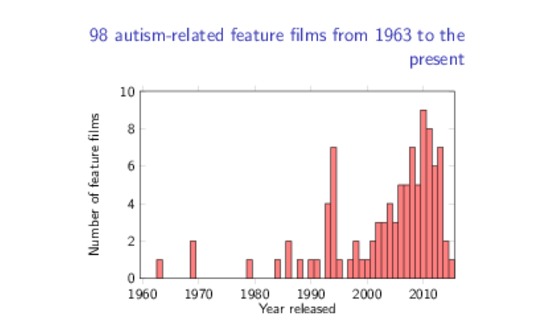

98 Autism-related feature films from 1963 to the present

Feature films have a pivotal role in forming public perception of what ‘autism’ means, and in educating psychiatrists, first responders (police, paramedics and frontline staff). I w as surprised not just by the sheer number of feature films ‘about’ autism, but also by how many films preceded “Rain Man” (1988), which is often seen as the turning point in autism films.

The list here deliberately includes any film that people believe to be ‘about autism’ (whether I agree or not), because these beliefs are the public perception that defines what ‘autism’ is.

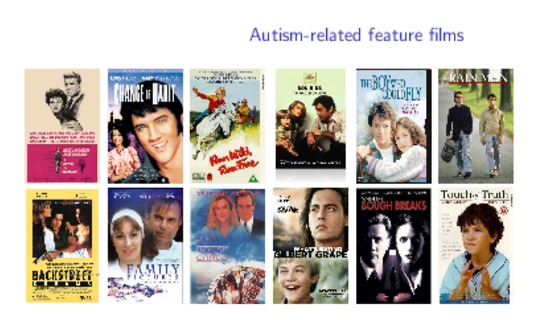

Autism-related feature films – the first “autism film” is probably one of these:

- 1963: “A Child Is Waiting” with Burt Lancaster as Dr. Matthew Clark and Judy Garland as Jean Hansen

- 1969: “Change of Habit” with Elvis Presley as Dr. John Carpenter and Mary Tyler Moore as Sister Michelle

- 1969: “Run Wild, Run Free” with John Mills as The Moorman (Colonel) and Mark Lester as Phillip Ransome

- 1979: “Son-Rise: A Miracle of Love” with James Farentino as Bears Kaufman, Kathryn Harrold as Suzi Kaufman and (twins) Michael and Casey Adams as Raun Kaufman

- 1986: “The Boy Who Could Fly” with Lucy Deakins as Amelia “Milly” Michaelson and Jay Underwood as Eric Gibb

- 1988: “Rain Man” with Dustin Hoffman as Raymond Babbitt and Tom Cruise as Charlie Babbitt

- 1990: “Backstreet Dreams” with Jason O’Malley as Dean, Brooke Shields as (Dr) Stevie and John and Joseph Vizzi as Shane

- 1993: “Family Pictures” with Anjelica Huston as Lainey Eberlin, Sam Neill as David Eberlin, Kyra Sedgwick as Nina Eberlin, Dermot Mulroney as Mack Eberlin and Jamie Harrold as Randall Eberlin

- 1993: “House of Cards” with Kathleen Turner as Ruth Matthews, Tommy Lee Jones as (Dr) Jake Beerlander and Asha Menina as Sally Matthews

- 1993: “What’s Eating Gilbert Grape” with Johnny Depp as Gilbert Grape, Juliette Lewis as Becky and Leonardo DiCaprio as Arnie Grape

- 1993: “When the Bough Breaks” with Ally Walker as Special Investigator Audrey Macleah, Martin Sheen Martin Sheen as Captain Swaggert, Ron Perlman as Dr. Douglas Eben and Tara Subkoff as Jordan Thomas / Jennifer Lynn Eben

- 1994: “Cries from the Heart” with Patty Duke as (Dr) Terry Wilson, Melissa Gilbert as Karen Barth and Bradley Pierce as Michael Barth

The underlined actor and character are the one with a diagnosis of autism. “Rain Man” (1988) was preceded by “A Child Is Waiting” (1963), “Change of Habit” (1969), “Run Wild, Run Free” (1969), “Son-Rise: A Miracle of Love” (1979) and “The Boy Who Could Fly” (1986).

We could decide, looking at these, what it means to say “about” autism, and whether these films are describing the same thing as we are describing, and whether the film is useful in dialogue (to speak for us) in explaining autism. There is no absolute right or wrong answer.

I am interested in whether films attempt (or can be co-opted) to speak for people with autism, or are written from the perspective of living with autism, or use actors with autism to portray autism.

(It is important to note that films are used to educate psychiatrists, which has a very real effect on mental health services if those films are inaccurate or stereotypical – for instance Dave & Tandon (2011) “Cinemeducation in psychiatry” includes “Box 1: Useful films for teaching psychiatry – Rainman (1988), Autism” and continues “Rainman (1988), starring Dustin Hoffman and Tom Cruise, is an Oscar-winning film. Hoffman won the award for his sensitive portrayal of autistic savant Raymond Babbitt, based on the real-life story of Bill Sackter, a friend of Barry Morrow, the director of the film. The film can be used to stimulate discussion on a variety of topics, including diagnostic criteria of autism‐spectrum disorders, impact on carers and the role of institutional care, but is also excellent to demonstrate the range of verbal and motor tics and mannerisms displayed by Babbitt (0:36:30–0:38:24). Alexander’s (2004a) suggestion of playing a clip without the audio and then with sound to aid the understanding of non‐verbal communication is particularly relevant here.”)

A Bechdel Test for autism-related fiction

The Bechdel Test is named after the American cartoonist Alison Bechdel who, in 1985, had a character in her comic strip “Dykes to Watch Out For” voice the idea. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bechdel_test). The Bechdel Test requires a work of fiction to feature:

- at least two women

- who talk to each other

- about something other than a man

The Bechdel Test is a quick method of determining if films or fiction speak for women, or merely incorporate them as a plot device. A Bechdel Test for autism would require (on the basis of the films listed above):

- a character with autism

- who speaks

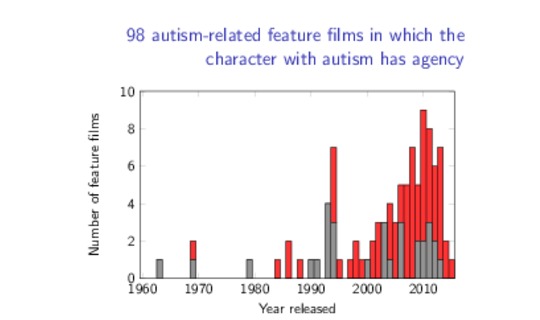

Characters with autism are often portrayed as the children of the leading actors, providing emotional crises and opportunities for the adults to express their character. The films, in the main, are not driven by the wishes of the character with autism and do not portray life with autism from their perspective. They are certainly not made by people with a diagnosis and do not employ actors with a diagnosis.

31 out of 98 (30%) autism-related feature films in which the character with autism has no agency

Films with “helpless” autism characters happen to peak at each change in the DSM – DSM-II in 1968, DSM-III in 1980, DSM-III-R in 1987, DSM-IV in 1994, DSM-IV-TR in 2000 and DSM-5 in 2013. This may be because film-makers meet public demand arising from news interest in autism that coincides with DSM revisions.

Only 2 characters with autism were portrayed by an actor with autism

- Poppy, played by Lizzy Clark in “Dustbin Baby” (2008)

- Jovana, played by Jovana Mitic in “Midwinter Night’s Dream (San zimske noci)” (2004)

(“Dustbin Baby” is a BBC made-for-television adaptation of Jacqueline Wilson’s 2001 novel of the same name. Lizzy Clark was the first actress with Asperger syndrome to portray a fictional character with the condition. “Midwinter Night’s Dream” is an allegory of the Balkan wars, starring an autistic child, Jovana Mitic, as the main character.)

Books

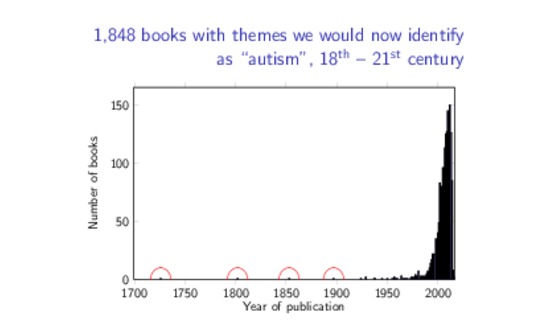

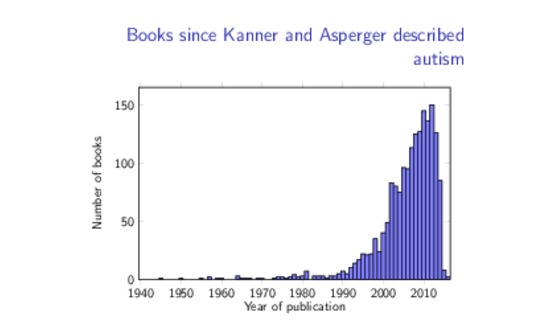

A list of 1,848 books with themes we would now identify as “autism”, from the 18th – 21st century

The sheer volume of books ‘about autism’ is phenomenal. I used publicly-created lists from several online sources, such as Goodreads.com, where two or more people agreed that a book was autism-related.

But who was writing about autism in 1726, 1802, 1853 and 1897?

The first “autism book” is possibly one of these: (unless you prefer Shakespeare, or Homer, or …)

- 1726: “Gulliver’s Travels” by Jonathan Swift

- 1802: “Victor, the Wild Boy of Aveyron” by Jean Marc Gaspard Itard

- 1853: “Bartleby, the Scrivener” by Herman Melville

- 1897: “Captains Courageous” by Rudyard Kipling

- 1924: “The Outsider” by H.P. Lovecraft

- 1929: “Passing” by Nella Larsen

- 1929: “The Sound and the Fury” by William Faulkner

- 1937: “Of Mice and Men” by John Steinbeck

- 1938: “Murphy” by Samuel Beckett

- 1938: “Rebecca” by Daphne du Maurier

- 1945: “Pippi Longstocking” by Astrid Lindgren

- 1950: “I, Robot” by Isaac Asimov

We see Jonathan Swift as well as Jean Marc Gaspard Itard’s “Victor, the Wild Boy of Aveyron”, Herman Melville and Rudyard Kipling. And again, it is up to us as individuals to decide what it means to write “about autism”, and each of us will have different answers.

(Paul Cefalu (2013) examines William Shakespeare’s Iago, in Othello, through the lens of Theory of Mind. Kristina Chew (2013) discusses the νήπιοι (young men) in Homer’s Iliad (c. 8th century BCE) through the lens of neurodiversity, comparing them with the πολύτροπος (much-travelled) Odysseus).

Jonathan Swift was addressing the contemporary issue of the abuse of mad people

Jonathan Swift was reacting to the inhumane treatment of mentally ill people in his time. When he died (aged 80, in 1745) he left the bulk of his estate (£12,000) to found St Patrick’s Hospital for Imbeciles, now St Patrick’s University Hospital.

He wrote about the Yahoos, a beast of burden with human appearance, “Here we entered, and I saw three of those detestable creatures, which I first met after my landing, feeding upon roots, and the flesh of some animals, which I afterwards found to be that of asses and dogs, and now and then a cow, dead by accident or disease. They were all tied by the neck with strong withes fastened to a beam; they held their food between the claws of their fore feet, and tore it with their teeth.”

He also described the people of Laputa, “it seems the minds of these people are so taken up with intense speculations, that they neither can speak, nor attend to the discourses of others, without being roused by some external taction upon the organs of speech and hearing; … [a] flapper is likewise employed diligently to attend his master in his walks, and upon occasion to give him a soft flap on his eyes; because he is always so wrapped up in cogitation, that he is in manifest danger of falling down every precipice”.

In “It Cannot Rain But It Pours, Or, London Strewed With Rarities” he described the real-life “wonderful Wild Man that was nursed in the woods of Germany by a wild beast, hunted and taken in toils & how he behaveth himself like a dumb creature, and is a Christian like one of us, being called Peter; and how he was brought to court all in green, to the great astonishment of the quality and gentry”. People asked if Peter did not speak, did he have a soul? Compare Swift’s use of “a Christian like one of us” with “un cretien sommes nous” (a cretin), used in Valais and Savoie, where the frequency of thyroid-related intellectual disability (cretinism) was high due to iodine deficiency. People were urged to treat their children as “cretien”, Christian or human, even if they did not have speech.

Books since Kanner and Asperger described autism

I know of only two published English-language fiction titles about autism, written by people with a diagnosis of autism

- “I’m Right Here” by Naoki Higashida (short story in “The Reason I Jump”, 2013)

- The “Mu Rhythm Bluff” by Jonathan Mitchell (2013) (http://www.amazon.com/The-Rhythm-Bluff-Jonathan-Mitchell-ebook/dp/B00BQN84GM)

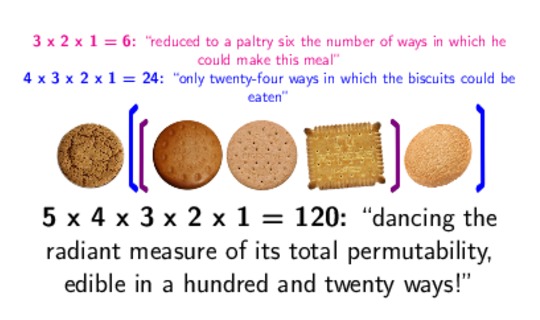

Murphy’s meal in “Murphy” by Samuel Beckett

Sometimes fiction (whatever the author’s intention) can be used to express aspects of autism well, whether or not it was written by someone who has a diagnosis. Many of the great writers have considered and written about conditions or states of mind that are like autism. What matters is whether they speak to us – or for us.

The character Murphy (who does not walk or wander, but “receded a little way into the north”) finds himself incapacitated by indecision and limited by rigid thinking in eating his lunch, a packet of 5 biscuits. These are “the same as always, a Ginger, an Osborne, a Digestive, a Petit Beurre and one anonymous”, yet his rigid need to save his favourite (the Ginger) until last and to dispose of the anonymous first leaves him only six permutations of eating the remining three biscuits. He will therefore repeat an identical lunch at least once a week.

He expresses this problem beautifully in mathematical form:

- 3 x 2 x 1 = 6: “reduced to a paltry six the number of ways in which he could make this meal”, or repetition at least once a week

- 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 24: “only twenty-four ways in which the biscuits could be eaten”, if he could conquer his prejudice against the anonymous – and almost an entire month of different permutations

- 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 120: “dancing the radiant measure of its total permutability, edible in a hundred and twenty ways!”, if he could overcome the final hurdle and allow himself to eat the Ginger in any order

This little vignette captures perfectly my own incapacity when faced with unwanted or unexpected choice in food, or attempts to eat in public places.

Taking ownership

It is a long march before people with autism control public perceptions about themselves, taking part in the direction and production of films or writing fiction about the lived experience of autism. We can all take our own first steps in choosing and promoting whatever film and fiction works for ourselves, as individuals, in explaining how we perceive our own lives. Some films or fiction may have little or nothing to do with autism per se, but may still function as a tool to advocate for specific issues that affect an individual life or specific problem.

Take ownership and share your experiences through film and fiction, driving the public percpetion of what “autism” is towards characters and situations that are realistic to you.

There are so much books that talks about autism but only few seems to be kind on their words. A lot of them took Autism as a disease.